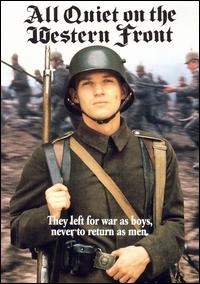

Eric Marie Remarque 1929

When we speak of the origins of 20th psychiatry, we often hear of the pioneering physicians – Emil Kraepelin, Eugen Bleuler, Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung, Adolf Meyer – to mention only a few. But we should add Kaiser Wilhelm II and Adolph Hitler to the list, because it was the great wars of the first half of the last century that put psychiatry on the map. World War I produced the largest epidemic of mental illness in our history. World War II lead to the import of preventive medicine into the field of mental illness.

Prior to World War I, traumatic mental illness was a little discussed topic. After our Civil War, Jacob Mendes Da Costa described a condition with dyspnea and tachycardia in veterans that came to be known as Soldier’s Heart [thought at the time to be due to damaged heart muscle]. Other than that, there were only some reports of behavioral syndromes following occupational accidents [also attributed to physical causes]. These things were on the back pages of the medical literature. But when World War I broke out, then settled into the horrors of trench warfare abetted by technological advances in killing power, there was an outbreak of battlefield insanity that not only made it to the front pages of the medical literature, but also to the newspapers on the home fronts of everyone involved – which was just about everyone, at least in the West.

Prior to World War I, traumatic mental illness was a little discussed topic. After our Civil War, Jacob Mendes Da Costa described a condition with dyspnea and tachycardia in veterans that came to be known as Soldier’s Heart [thought at the time to be due to damaged heart muscle]. Other than that, there were only some reports of behavioral syndromes following occupational accidents [also attributed to physical causes]. These things were on the back pages of the medical literature. But when World War I broke out, then settled into the horrors of trench warfare abetted by technological advances in killing power, there was an outbreak of battlefield insanity that not only made it to the front pages of the medical literature, but also to the newspapers on the home fronts of everyone involved – which was just about everyone, at least in the West.

A blog is no place for this picture except in the broadest of strokes. Early in the war, there were two responses – send the afflicted back home or execute them as cowards [a fate that befell hundreds, perhaps thousands after Russia entered the conflict]. But the age-old military concepts of bravery, honor, courage, and cowardice weren’t up to the magnitude of the problem. The soldiers themselves called it "shell shock," and the term was picked up by the military physicians who thought it was a result of some kind of brain injury from exploding ordinance. The military high command, on the other hand, leaned towards malingering as they saw their front lines dwindling. A compromise view resulted in "the Kaufman Cure" – primarily used by the Germans – a series of violent electric shocks applied to the affected part of the body. It often worked, although there were a significant number of fatalities from the procedure or suicide. Many saw this as an attempt to get the soldiers back fighting using aversive conditioning.

As the war wore on, it wasn’t just a problem of personnel management, it got into the area of disability compensation – and they developed elaborate strategies to "certify" illnesses, weed out the malingerers. On the British side, Dr. Charles Meyers, a physician and psychology professor at Cambridge was put in charge of these cases. He believed the brain damage theories and treated the British victims as medical cases – victims rather than "cowards.".

At some point, Dr. Harold Wiltshire was sent to look over the situation, and made some remarkable observations: He found no cases of Shell Shock on the medical wards where soldiers were recovering from massive physical injuries. And on the mental wards, there were few if any physical wounds. Further, in talking to the soldiers, most told him that there symptoms didn’t start on the battlefield but came of later when they reflected or when they encountered some graphic visual reminder of the horrors of war. His observations put the nail in the coffin of brain injury as the cause of "Shell Shock." Two other British physicians, A.J. Brock and William Halse Rivers were in charge of a hospital for afflicted officers in Craiglockhart, Scotland and developed more psychological treatments – psychotherapy, vocational therapy.

In Germany, Sigmund Freud joined others in a Commission that opposed and put to an end the "Kauffman Cure" as a "barbaric" intrusion of military expediency into the ranks of medicine. Freud abandoned his early ideas about treatment, because he thought the disorder would disappear after the war – which was totally wrong as the streets of Europe filled with very visible victims. That lead him to a book in 1921, Beyond the Pleasure Principle, about traumatic neurosis. It’s a little-read book cached in anachronistic instinct terms, but many people interested in traumatic illness see it at a deeper level as Freud’s finest hour [present company included].

World War I produced some of our greatest literature. The group known as the British War Poets, many former patients at Craiglockhart, wrote eloquently of the horrors of the war [Sassoon, previous post]. Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front, an autobiographical novel from a German veteran, remains a cherished classic. Likewise, Robert Graves’ autobiographical account of his war experiences as a British officer, Good-bye to All That, continues to be a major resource for his descriptions of the war experience in general and for his personal observations on the development of war related illnesses. Virginia Woolf’s revolutionary interior novel, Mrs. Dalloway, hinges on her character’s reflections the suicide of a "Shell Socked" man [Septimus]. And all of us know of J.R.R. Tolkein’s magnum opus [The Lord of the Rings], written to help him deal with and contain his experiences in the trenches of World War I.

Soldier’s heart sounds like the cardiac changes that were initially described in the 80s in African Americans–especially those who lived in poor, violent neighborhoods that required constant vigilance, and which predisposed them to early death.