… Under the terms of the insurance derivatives that the London unit underwrote, customers paid a premium to insure their debt for a period of time, usually four or five years, according to the company. Many European banks, for instance, paid A.I.G. to insure bonds that they held in their portfolios. Because the underlying debt securities — mostly corporate issues and a smattering of mortgage securities — carried blue-chip ratings, A.I.G. Financial Products was happy to book income in exchange for providing insurance. After all, Mr. Cassano and his colleagues apparently assumed, they would never have to pay any claims.

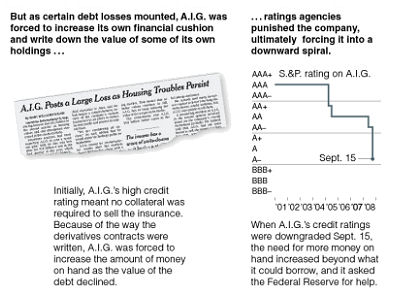

Since A.I.G. itself was a highly rated company, it did not have to post collateral on the insurance it wrote, analysts said. That made the contracts all the more profitable. These insurance products were known as “credit default swaps,” or C.D.S.’s in Wall Street argot, and the London unit used them to turn itself into a cash register.

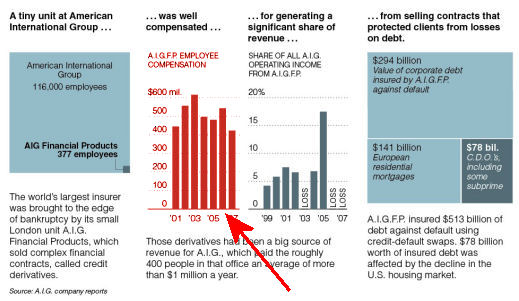

The unit’s revenue rose to $3.26 billion in 2005 from $737 million in 1999. Operating income at the unit also grew, rising to 17.5 percent of A.I.G.’s overall operating income in 2005, compared with 4.2 percent in 1999. Profit margins on the business were enormous. In 2002, operating income was 44 percent of revenue; in 2005, it reached 83 percent.

Mr. Cassano and his colleagues minted tidy fortunes during these high-cotton years. Since 2001, compensation at the small unit ranged from $423 million to $616 million each year, according to corporate filings. That meant that on average each person in the unit made more than $1 million a year. In fact, compensation expenses took a large percentage of the unit’s revenue. In lean years it was 33 percent; in fatter ones 46 percent. Over all, A.I.G. Financial Products paid its employees $3.56 billion during the last seven years…

The insurance giant’s London unit was known as A.I.G. Financial Products, or A.I.G.F.P. It was run with almost complete autonomy, and with an iron hand, by Joseph J. Cassano, according to current and former A.I.G. employees. A onetime executive with Drexel Burnham Lambert — the investment bank made famous in the 1980s by the junk bond king Michael R. Milken, who later pleaded guilty to six felony charges — Mr. Cassano helped start the London unit in 1987.

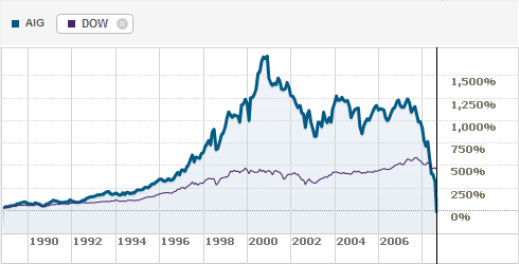

The unit became profitable enough that analysts considered Mr. Cassano a dark horse candidate to succeed Maurice R. Greenberg, the longtime chief executive who shaped A.I.G. in his own image until he was ousted amid an accounting scandal three years ago. But last February, Mr. Cassano resigned after the London unit began bleeding money and auditors raised questions about how the unit valued its holdings. By Sept. 15, the unit’s troubles forced a major downgrade in A.I.G.’s debt rating, requiring the company to post roughly $15 billion in additional collateral — which then prompted the federal rescue.

Mr. Cassano, 53, lives in a handsome, three-story town house in the Knightsbridge neighborhood of London, just around the corner from Harrods department store on a quiet square with a private garden…

So where is the money? The builder/developer has made a fine profit in the booming housing market. The real estate people have made a bundle in the booming real estate market. The bank has made a bundle by closing the loans and selling them on a booming mortgage commodity market. The insurer[?] has made a bundle from insurance premiums [without having to have the capital to back up the liability]. The stockholders’ retirement plans are substantially fattened. Then the housing market turns downwards and…

[…] that than I did. A bunch of it is in the bank accounts of Mortgage Brokers like Joseph J. Cassano [“follow the [unregulated] money”…]. A lot of it was "bubbleware," virtual money that was not backed up by real value [the […]