Then, as now, I came back thinking about the neoconservative obsession with "regime change" in Iraq and Iran. They wanted that desert with all their hearts. While the PNAC letter to President Clinton in 1998 is well known [they’ve pulled the web site again but I keep a copy handy], there are a few other references that remain more obscure:

|

January 26, 1998

The Honorable William J. Clinton Dear Mr. President: We are writing you because we are convinced that current American policy toward Iraq is not succeeding, and that we may soon face a threat in the Middle East more serious than any we have known since the end of the Cold War. In your upcoming State of the Union Address, you have an opportunity to chart a clear and determined course for meeting this threat. We urge you to seize that opportunity, and to enunciate a new strategy that would secure the interests of the U.S. and our friends and allies around the world. That strategy should aim, above all, at the removal of Saddam Hussein’s regime from power. We stand ready to offer our full support in this difficult but necessary endeavor. The policy of “containment” of Saddam Hussein has been steadily eroding over the past several months. As recent events have demonstrated, we can no longer depend on our partners in the Gulf War coalition to continue to uphold the sanctions or to punish Saddam when he blocks or evades UN inspections. Our ability to ensure that Saddam Hussein is not producing weapons of mass destruction, therefore, has substantially diminished. Even if full inspections were eventually to resume, which now seems highly unlikely, experience has shown that it is difficult if not impossible to monitor Iraq’s chemical and biological weapons production. The lengthy period during which the inspectors will have been unable to enter many Iraqi facilities has made it even less likely that they will be able to uncover all of Saddam’s secrets. As a result, in the not-too-distant future we will be unable to determine with any reasonable level of confidence whether Iraq does or does not possess such weapons. Such uncertainty will, by itself, have a seriously destabilizing effect on the entire Middle East. It hardly needs to be added that if Saddam does acquire the capability to deliver weapons of mass destruction, as he is almost certain to do if we continue along the present course, the safety of American troops in the region, of our friends and allies like Israel and the moderate Arab states, and a significant portion of the world’s supply of oil will all be put at hazard. As you have rightly declared, Mr. President, the security of the world in the first part of the 21st century will be determined largely by how we handle this threat. Given the magnitude of the threat, the current policy, which depends for its success upon the steadfastness of our coalition partners and upon the cooperation of Saddam Hussein, is dangerously inadequate. The only acceptable strategy is one that eliminates the possibility that Iraq will be able to use or threaten to use weapons of mass destruction. In the near term, this means a willingness to undertake military action as diplomacy is clearly failing. In the long term, it means removing Saddam Hussein and his regime from power. That now needs to become the aim of American foreign policy. We urge you to articulate this aim, and to turn your Administration’s attention to implementing a strategy for removing Saddam’s regime from power. This will require a full complement of diplomatic, political and military efforts. Although we are fully aware of the dangers and difficulties in implementing this policy, we believe the dangers of failing to do so are far greater. We believe the U.S. has the authority under existing UN resolutions to take the necessary steps, including military steps, to protect our vital interests in the Gulf. In any case, American policy cannot continue to be crippled by a misguided insistence on unanimity in the UN Security Council. We urge you to act decisively. If you act now to end the threat of weapons of mass destruction against the U.S. or its allies, you will be acting in the most fundamental national security interests of the country. If we accept a course of weakness and drift, we put our interests and our future at risk. Sincerely, Elliott Abrams Richard L. Armitage William J. Bennett

Jeffrey Bergner John Bolton Paula Dobriansky

Francis Fukuyama Robert Kagan Zalmay Khalilzad

William Kristol Richard Perle Peter W. Rodman

Donald Rumsfeld William Schneider, Jr. Vin Weber

Paul Wolfowitz R. James Woolsey Robert B. Zoellick

|

Defending Liberty in a Global Economy

Delivered at the Collateral Damage Conference

Cato Institute

June 23, 1998

by Richard B. CheneyI believe that economic forces have driven much of the change in the last 20 years, and I would be prepared to argue that, in many cases, that economic progress has been a prerequisite to political change. The power of ideas, concepts of freedom and liberty and of how best to organize economic activity, have been an essential, positive ingredient in the developments in the last part of the 20th century. At the heart of that process has been the U.S. business community. Our capital, our technology, our entrepreneurship has been a vital part of those forces that have, in fact, transformed the world. Our economic capabilities need to be viewed, I believe, as a strategic asset in a world that is increasingly focused on economic growth and the development of market economies.

I think it is a false dichotomy to be told that we have to choose between "commercial" interests and other interests that the United States might have in a particular country or region around the world. Oftentimes the absolute best way to advance human rights and the cause of freedom or the development of democratic institutions is through the active involvement of American businesses. Investment and trade can oftentimes do more to open up a society and to create opportunity for a society’s citizens than reams of diplomatic cables from our State Department.

I think it’s important for us to look on U.S. businesses as a valuable national asset, not just as an activity we tolerate, or a practice that we do not want to get too close to because it involves money. Far better for us to understand that the drive of American firms to be involved in and shape and direct the global economy is a strategic asset that serves the national interest of the United States…

Full text of Dick Cheney’s speech at the Institute of Petroleum Autumn lunch, 1999

London Institute of Petroleum

by Dick Cheney… we as an industry have had to deal with the pesky problem that once you find oil and pump it out of the ground you’ve got to turn around and find more or go out of business. Producing oil is obviously a self-depleting activity. Every year you’ve got to find and develop reserves equal to your output just to stand still, just to stay even. This is true for companies as well in the broader economic sense as it is for the world. A new merged company like Exxon-Mobil will have to secure over a billion and a half barrels of new oil equivalent reserves every year just to replace existing production. It’s like making one hundred per cent interest discovery in another major field of some five hundred million barrels equivalent every four months or finding two Hibernias a year.

For the world as a whole, oil companies are expected to keep finding and developing enough oil to offset our seventy one million plus barrel a day of oil depletion, but also to meet new demand. By some estimates there will be an average of two per cent annual growth in global oil demand over the years ahead along with conservatively a three per cent natural decline in production from existing reserves. That means by 2010 we will need on the order of an additional fifty million barrels a day. So where is the oil going to come from?

Governments and the national oil companies are obviously controlling about ninety per cent of the assets. Oil remains fundamentally a government business. While many regions of the world offer great oil opportunities, the Middle East with two thirds of the world’s oil and the lowest cost, is still where the prize ultimately lies, even though companies are anxious for greater access there, progress continues to be slow. It is true that technology, privatisation and the opening up of a number of countries have created many new opportunities in areas around the world for various oil companies, but looking back to the early 1990’s, expectations were that significant amounts of the world’s new resources would come from such areas as the former Soviet Union and from China. Of course that didn’t turn out quite as expected. Instead it turned out to be deep water successes that yielded the bonanza of the 1990’s…

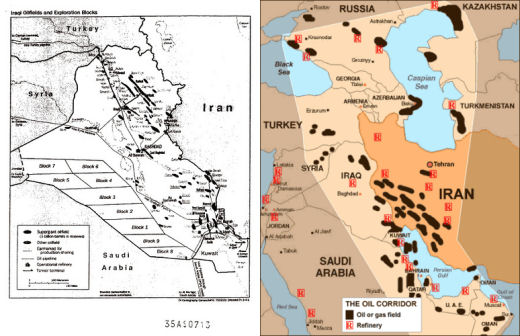

Left: Cheney’s Energy Task Force Map

Right: The Middle Eastern Oil Corridor

I think the evidence is strong enough to say that Dick Cheney set out to get our government involved in setting the stage for oil exploration in the Middle East by American Oil Companies – Iraq for sure and probably Iran later. Likewise, I think there’s enough evidence to say that our first Gulf War with Saddam Hussein’s Iraq had something to do with Kuwait’s oil production. It’s time to move those charges from the area of suspicions to the category of facts. I don’t think we could say that the pugilism towards the United States from Iraq and Iran is completely due to our aggression and oil-lust, but I do think it must be a factor.

I think it is a false dichotomy to be told that we have to choose between "commercial" interests and other interests that the United States might have in a particular country or region around the world. Oftentimes the absolute best way to advance human rights and the cause of freedom or the development of democratic institutions is through the active involvement of American businesses. Investment and trade can oftentimes do more to open up a society and to create opportunity for a society’s citizens than reams of diplomatic cables from our State Department.I think it’s important for us to look on U.S. businesses as a valuable national asset, not just as an activity we tolerate, or a practice that we do not want to get too close to because it involves money. Far better for us to understand that the drive of American firms to be involved in and shape and direct the global economy is a strategic asset that serves the national interest of the United States.

Oil remains fundamentally a government business. While many regions of the world offer great oil opportunities, the Middle East with two thirds of the world’s oil and the lowest cost, is still where the prize ultimately lies, even though companies are anxious for greater access there, progress continues to be slow.

-

Because it’s true. They know it. We know it [Cheney already said it in those early speeches]. We cannot negotiate honestly with either the Iraqis or the Iranians without some kind of acknowledgment of our true motives. There’s nothing wrong with our wanting oil, but there’s plenty wrong with trumping up bogus excuses to get it.

-

We are going to have to deal with Iran’s nuclear ambitions [if the Iranian people don’t do that for us]. We have to make it crystal clear that endeavor is not connected to a hidden agenda – going after their oil. Cheney and friends tried to hide it in Iraq, and nobody bought it.

-

Our national pride is in the tank. I can’t see any way to deal with it that avoids coming clean about our recent past. The collective "we" blew it. Blaming Bu$hCo isn’t enough. We have to face what "we" did.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.