Plot summary: The life of spoiled Robert Merrick is saved through the use of a hospital’s only pulmotor, but because the medical device cannot be in two places at once, it results in the death of Dr. Hudson, a selfless, brilliant surgeon and generous philanthropist. Merrick falls in love with Hudson’s widow, Helen, though she holds him responsible for her husband’s demise. One day, he insists on driving her home and makes a pass at her. She gets out and is struck by another car, losing her sight. He watches over her and visits her during her recuperation, concealing his identity and calling himself Dr. Robert. When he finds out that she is nearly penniless, he secretly pays for specialists to try to restore her vision. Finally, she travels to Paris and is told that her eyesight is gone forever. Robert follows her, confesses his true identity and proposes marriage. She forgives him, but goes away, not wanting to be a burden to him. Years later, Robert has become a brain surgeon. He learns that Helen urgently needs an operation, which he performs. When she awakens, her sight has miraculously returned. Plot summary: The life of spoiled Robert Merrick is saved through the use of a hospital’s only pulmotor, but because the medical device cannot be in two places at once, it results in the death of Dr. Hudson, a selfless, brilliant surgeon and generous philanthropist. Merrick falls in love with Hudson’s widow, Helen, though she holds him responsible for her husband’s demise. One day, he insists on driving her home and makes a pass at her. She gets out and is struck by another car, losing her sight. He watches over her and visits her during her recuperation, concealing his identity and calling himself Dr. Robert. When he finds out that she is nearly penniless, he secretly pays for specialists to try to restore her vision. Finally, she travels to Paris and is told that her eyesight is gone forever. Robert follows her, confesses his true identity and proposes marriage. She forgives him, but goes away, not wanting to be a burden to him. Years later, Robert has become a brain surgeon. He learns that Helen urgently needs an operation, which he performs. When she awakens, her sight has miraculously returned. |

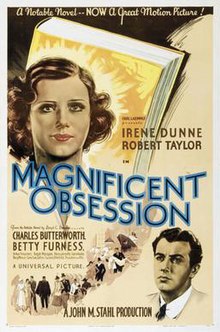

Those were the days when the big screen could resolve any tragedy into a triumph of the the human spirit – as in Lloyd C. Douglas’ 1935 Magnificent Obsession. We know this theme best from Scarlett’s 1939 soliloquy, "Tomorrow is another day!" in Gone with the Wind. We’d moved a long way from the Greek Tragedies or Shakespeare where tragic character flaws lead to inevitable ruin. The 1930s were a time when the themes of redemption in the cinema offered temporary respit from the terror and hardship of the Depression, the inklings of the coming War. But in practice, an obsession only becomes magnificent if it prevails against all odds. Otherwise, it’s just an obsession – clinging to an idea well beyond the time when the evidence has clearly negated any chance of success.

Which logically brings us to the story of the modern antidepressants [SSRIs, Bupropion, and SNRIs]. Eli Lilly’s Prozac came on the scene in 1987, around the time I was beginning a private practice. We all remember the excitement of the time. The tricyclic antidepressants had been around for a long time and most of us thought of them as treatment for the severe depressions. Although the DSM-III had thrown those syndromes into the wastebasket of Major Depressive Disorder, we still remembered their names [Melancholia, Involutional Depression, Post-partum Depression, etc.] and still used the terms [because the patients were still there in spite of their un-naming]. But the tricyclics were, at best, only maybe drugs in the more common depressed patients we saw. Prozac changed all of that, followed by an army of me-too antidepressants. In short order, all Depressions were Major Depressive Disorders, and the treatment for Major Depressive Disorder became the antidepressant du jour. In a more subtle way, depression itself became biology, neuroscience, chemical imbalance. Prior to that, the consensus had been that many of the severe depressive syndromes were biologic, but that moniker was extended to all depression after the coming of Prozac and friend.

As cracks began to appear in House SSRI, there was a concerted effort to un-see them [matching the persistent un-naming of the classic depressive syndromes]. Decreased libido, erectile dysfunction, anorgasmia, akisthisia, suicidal thinking, withdrawal syndromes – one by one, they were resisted vigorously as they appeared by both the pharmaceutical industry and their psychiatric Key Opinion Leaders – a story you know all too well. But then the foundation began to crack as well when the efficacy itself came into question. It came slowly. "They don’t work as well as we’d like" became "they don’t work very well" on the way to "Do they even work at all?" To the clinical neuroscientists who had put all of their eggs in that basket, that was an intolerable progression. Thus was born the magnificent obsession that these hallowed medications just had to work – maybe they were just being given in the wrong way; maybe they needed to be augmented, sequenced, or combined; maybe there’s a biosignature that will predict who will respond.

Clinician-rated symptom measures, while time-consuming, provide a firm basis for making strategic [e.g., switching or augmenting treatment] or tactical [e.g., dose adjustments, starting side effect treatments, etc.] decisions. Thus, the routine use of clinical rating scales seems justified.

So in the 16 years since publishing the Treatment of Depression to Remission, Rush and Trivedi masterminded four major implementations of their concept of measurement-based care using sequencing algorithms or combination therapy aiming for remission [TMAP, STAR*D, IMPACTS, CO-MED]. All four studies were government financed [expensive undertakings]. One was part of a huge pharmaceutical fraud. All four were failed studies. Rarely mentioned is the fact that the algorithms themselves were all arbitrary sequences created by the authors based on… I don’t know what they were based on. One might have thought that they had amassed enough evidence to conclude that measurement-based, evidence-based,, remission-bound, algorithmic treatment wasn’t working out so well after all. And these studies spanned a period when there was a growing consensus that the antidepressants were much less efficacious and more toxic than advertised – by anyone’s measure.

Report by the ACNP Task Force on response and remission in major depressive disorder.

by Rush AJ, Kraemer HC, Sackeim HA, Fava M, Trivedi MH, Frank E, Ninan PT, Thase ME, Gelenberg AJ, Kupfer DJ, Regier DA, Rosenbaum JF, Ray O, and Schatzberg AF; ACNP Task Force.

Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006 Sep;31(9):1841-53.

[full text on-line]

This report summarizes recommendations from the ACNP Task Force on the conceptualization of remission and its implications for defining recovery, relapse, recurrence, and response for clinical investigators and practicing clinicians. Given the strong implications of remission for better function and a better prognosis, remission is a valid, clinically relevant end point for both practitioners and investigators. Not all depressed patients, however, will reach remission. Response is a less desirable primary outcome in trials because it depends highly on the initial (often single) baseline measure of symptom severity. It is recommended that remission be ascribed after 3 consecutive weeks during which minimal symptom status (absence of both sadness and reduced interest/pleasure along with the presence of fewer than three of the remaining seven DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criterion symptoms) is maintained. Once achieved, remission can only be lost if followed by a relapse. Recovery is ascribed after at least 4 months following the onset of remission, during which a relapse has not occurred. Recovery, once achieved, can only be lost if followed by a recurrence. Day-to-day functioning and quality of life are important secondary end points, but they were not included in the proposed definitions of response, remission, recovery, relapse, or recurrence. These recommendations suggest that symptom ratings that measure all nine criterion symptom domains to define a major depressive episode are preferred as they provide a more certain ascertainment of remission. These recommendations were based largely on logic, the need for internal consistency, and clinical experience owing to the lack of empirical evidence to test these concepts. Research to evaluate these recommendations empirically is needed.

-

specifically and repeatedly measure core criterion depressive symptom severity to guide the implementation and timely modification of treatment,

-

conduct sufficient visits or measurements to establish that 3 consecutive weeks of minimal to no symptoms [ie, remission] has or has not been achieved,

-

systematically inquire about the magnitude and types of side effects and overall side-effect burden, so as to accurately gauge whether the dose or type of treatment needs modification in order to achieve remission in a time-efficient fashion, and

-

follow the trajectory of symptom change [or lack of change] such that treatments [dose, type] can be modified in a timely fashion, hopefully informed by empirically defined triage points.

Measurement-based care for unipolar depression

by Morris DW and, Trivedi MH

Current Psychiatry Report. 2011 13(6):446-58.This article outlines the role of measurement-based care in the management of antidepressant treatment for patients with unipolar depression. Using measurement-based care, clinicians and researchers have the opportunity to optimize individual treatment and obtain maximum antidepressant treatment response. Measurement-based care breaks down to several simple components: antidepressant dosage, depressive symptom severity, medication tolerability, adherence to treatment, and safety. Quick and easy-to-use, empirically validated assessments are available to monitor these areas of treatment. Utilizing measurement-based care has several steps-screening and antidepressant selection based upon treatment history, followed by assessment-based medication management and ongoing care. Electronic measurement-based care systems have been developed and implemented, further reducing the burden on patients and clinicians. As more treatment providers adopt electronic health care management systems, compatible measurement-based care antidepressant treatment delivery and monitoring systems may become increasingly utilized.

Performance improvement CME: algorithms and EMRs in depression

by Shelton RC and Trivedi MH

Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2011 72(9):e29.

Major depressive disorder is difficult to treat due to its chronic and recurrent nature and the poor performance of most pharmacologic treatment options. To improve patient outcomes, clinicians should become familiar with moderators of antidepressant response, implement measurement-based care, and follow treatment algorithms. The use of electronic medical records and computerized decision support systems may improve documentation and facilitate clinicians’ adherence to current standards of care. This Performance Improvement activity focuses on improving treatment outcomes for antidepressant therapy through familiarity with moderators of antidepressant response and the use of treatment algorithms, measurement-based care, and electronic medical records.

I’ll leave you on your own to read further about what they have in mind. But it’s the same thing I’ve been trying to talk about in this whole post – the magnificent obsession with the idea that if the entire process of treatment is under tight control with algorithms and measurements, outcome will be improved. It sounds to me more like a plan to make mental health care something that anyone can do using a computer and patient rating scales. It’s an extrapolation of the notion of Managed Care carried to an extreme. And perhaps that’s exactly what it is, explaining why the idea persists even though its track record in every one of the alphabet studies where it has been implemented is abysmal. In the study most like what they’re proposing here, IMPACTS, they couldn’t even get their doctors to do it, much less look at the outcome. And yet they persist. Surely there’s a reason that this idea won’t die.

I’ll leave you on your own to read further about what they have in mind. But it’s the same thing I’ve been trying to talk about in this whole post – the magnificent obsession with the idea that if the entire process of treatment is under tight control with algorithms and measurements, outcome will be improved. It sounds to me more like a plan to make mental health care something that anyone can do using a computer and patient rating scales. It’s an extrapolation of the notion of Managed Care carried to an extreme. And perhaps that’s exactly what it is, explaining why the idea persists even though its track record in every one of the alphabet studies where it has been implemented is abysmal. In the study most like what they’re proposing here, IMPACTS, they couldn’t even get their doctors to do it, much less look at the outcome. And yet they persist. Surely there’s a reason that this idea won’t die.-

Depressed people are easily diagnosed from the DSM-x symptom list.

-

The treatment is antidepressant medications picked by an algorithm.

-

The progress can be followed using a questionnaire.

-

Based on the results, medications are adjusted using the algorithm.

The magnificent obsession with measurement-based, evidence-based, algorithmic treatment is good for the insurance carriers. We know it’s good for the pharmaceutical industry in that every depressed person is automatically a customer. Is it good for psychiatrists? Hardly. It aims for psychiatrists to become obsolete except as algorithm expeditors. But the point is really "Is it good for patients?" Not according to the studies of Drs. Rush and Trivedi. Not according to the Clinical Trials that pepper our literature. In spite of the injunction to treat to remission, the patients drop out like flies or report only minor improvements on their collective questionnaires at the very best. And even looking at the placebo responses in clinical trials, the non-drop-outs improve too. So it’s not going to come out like the book or the movie – the Magnificent Obsession. It’s going to come out like it has for Drs. Rush and Trivedi repeatedly – a failed clinical trial – perpetuating the overvaluing and over-prescription of medication to the detriment of sick people. And it’s going to burden practitioners with more hassle and external control, until the only psychiatrists left standing are the KOLs who are out hustling primary care physicians to take it over.

More to the point, why is the DSM-5 Task Force incorporating this injunction to practice measurement-based, evidence-based, algorithmic care into our diagnostic system of all places? It’s certainly not based on results. Who told the APA that it was their job to shape the future practice of psychiatry using a diagnostic classification revision? Or to move the treatment of depression into primary care? Since when was a diagnostic manual a vehicle for introducing a system that benefits the insurance and pharmaceutical industries but neither the psychiatrists nor patients? And what does such a system do for the psychologists, the social workers, and the counselors whose treatment has nothing to do with these simplistic medication/questionnaire/algorithm fantasies of non-practicing psychiatrists, having used our manual thinking it was an authoritative compendium of mental illnesses?

Each post you share could – and should – serve as a Grand Rounds presentation. Your generous sharing of your wisdom and knowledge is greatly appreciated.

Navigating through this mess and actually finding and accessing beneficial treatment is impossible. The harms vastly outweigh the benefits where treatment exists – and it doesn’t exist, for the most part.

Your patients are incredibly fortunate that you are still keeping a hand in.

I love your blog and read it faithfully if often with a heavy heart. As someone who has both suffered from what to call it these days–major major depressive disorder, I would like you to say something about the fact that SSRIs though not the be-all and end-all of treatment DO help. And sometimes the side effects are worth it. I do basically agree with you though that the whole evidence-based, statistical, questionnaire based approach to treatment is nightmarish to say the least. You might be interested in this post today on Thought Broadcast: http://thoughtbroadcast.com/2011/12/05/we-do-not-know-what-we-cannot-know/ . What matters is medicine as a tool in the hands of compassionate, observant, wise practitioners.

Thanks Esther. I’m not an anti-psychiatrist or even anti-medication. I prescribe antidepressants too. They unquestionably help some people. I even think I can sort of tell who they’re going to help, though not well enough to do a John Henry challenge. Your point is on target. Drugs are simply tools that have upsides and downsides. They need watching carefully. I don’t need a qids-sr or other rating scale to know if they help. The patient will be glad to tell me. I do need to know the person I’m treating and the side effects. But there’s more to being a depressed person than just symptoms and just needing medication. Rush and Trivedi don’t want us to notice that.

Mickey:

Great post as usual. One component of this ‘Magnificent Obsession†of Rush et al’s part is to eviscerate traditional psychiatric practice (which you so well point out). Besides the fact that Rush and company should of reported their results as pre-specified, my main issue with STAR*D has always been that IF they had presented the results as pre-specified back in 2006, we’d be a lot further ahead in thinking through how to improve the outcomes for the kinds of very mild to more severely depressed people who present for treatment at PCP and psychiatry clinics…basically, we’d be trying anything but what STAR*D had done. Instead, STAR*D’s results got interpreted to the broader medical community that depression can be successfully treated by PCPs using their ‘measurement-based system of care’ including the use of combination antidepressant treatments.

I’m back channeling you their 2008 article published in the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. The opening states, “Depression can be treated successfully by primary care physicians under “real world†conditions. Furthermore, the particular drug or drugs used are not as important as following a rational plan: giving antidepressant medications in adequate doses, monitoring the patient’s symptoms and side effects and adjusting the regimen accordingly, and switching drugs or adding new drugs to the regimen only after an adequate trial.â€

This same point is made in their 2009 Psychiatric Services article (an APA journal no less) where on p. 1444 they state, “No statistically significant difference in outcome was found between patients treated in primary care and psychiatric settings when measurement-based care was used in level 1 or level 2. Thus primary care physicians, who manage the majority of depressed patients, can be reasonable providers of depression care for at least the first two treatment steps†(back channeled as well).

This is not what the results showed, and if I were a psychiatrist, I’d be rather upset/pissed to have them portrayed this way (and this in an APA journal no less). If you look at their ‘measurement based care’ methodology, all that they showed is that by using their system, combined with onsite Clinical Research Coordinators who essentially dictated care to the ‘treating’ physician, there were consistently poor outcomes across treatment sites with no differences in outcomes across their 23 psychiatric and 18 PCP participating clinics.

From my perspective, their ‘measurement-based care’ system neutered psychiatrists’ expertise yet then used this to say that there was no difference in effectiveness between PCPs and psychiatrists. Now, the fact that Rush holds a proprietary, royalty-producing, interest in the key component of this measurement-based system of care is I’m certain just due to fortunate happenstance for him…or on the other hand, it may help to explain this long sustained obsession ïŠ!

Again from my perspective, Rush and company (& their enablers at NIMH, Psychiatric Services, & within APA) are the anti-psychiatrists,

Ed

Thanks Ed. They are antipsychiatrists. Reading Kupfer and Regier, particularly in the Cross-Cutting Dimensional Assessment section, suggest to me that they are too. If what they propose actually worked, Psychiatrists would gladly comply. The problem is it doesn’t, so they are stuck with moving their plan to some place where the lackluster efficacy won’t be noticed. It’s a sad story…

Thanks for the post, Mickey.

Another interesting aspect of the TMAP story is the role played by then chief of the department of psychiatry Kenneth Altshuler. He served on the board of the Texas Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation and the American Psychiatric Association’s Council of Medical Specialty Societies. And he was a member of the Dallas Psychoanalytic Institute (DPI).

Interestingly, the DPI (now Dallas Psychoanalytic Center) newsletters for 1999 through 2009 made no mention of the shenanigans in the department of psychiatry. It appears that Rush and company had a cavalry of enablers. See page 4 at

http://www.dalpsa.org/Newsletters/N12_Spring_2000.pdf

This is off topic, but a link to a Boston.com slash Boston Globe business article about the “blending” in of the pharma giants and newcomers with MIT, Harvard and direct care organizations. Subtle, marketed to appear cutting edge and economy growth benefits, and oh-so-slick business community COI acceptance manipulation, don’t you think?

http://www.boston.com/business/healthcare/articles/2011/12/08/novartis_mixing_art_with_science/?p1=News_links