DSM Field Trials Providing Ample Critical Data

Psychiatric News

by David J. Kupfer, M.D.

May 4, 2012

As of this month, the 12-month countdown to the release of the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM-5] officially begins. While the developers of DSM-5 will continue to face several deadlines over the coming year, the progress that has been made since APA’s 2011 annual meeting has been nothing short of remarkable. One of the most notable and talked-about recent activities of the DSM revision concerns the implementation and conclusion of the DSM-5 Field Trials, which were designed to study proposed changes to the manual. This included both the examination of specific diagnostic criteria as well as overarching changes applicable across disorders, like the integration of dimensional measures and diagnostic severity scales. The DSM-5 Field Trials used two study designs — a large-scale design implemented across 11 medical-academic centers and a second design that was created specifically for solo and small-group clinicians in routine clinical practice [RCP] settings.Both types of field trials provided landmark opportunities to study DSM in a more rigorous manner than field assessments in previous iterations of DSM. Specifically, they provided the rare opportunity to better understand the reliability, clinical utility, and feasibility of proposed changes in both high-volume research-practice settings and in everyday clinical care settings. This means that findings from the DSM-5 Field Trials will be generalizable to the actual patient groups diagnosed with the manual—unlike the tightly controlled field trials in DSM-IV that used preselected patients with predetermined diagnoses. Recruiting actual clinicians and patients, rather than relying on DSM Task Force members as participants, also reduces our chances of having biased findings.

Additionally, we examined the proposed changes to DSM among a wide variety of populations, varying in age, diagnosis, and ethnic background. And diagnostic interviews were conducted not just by psychiatrists but psychologists, counselors, psychiatric nurses, and family and marriage therapists; this is particularly important given the range of users who will use DSM-5 in their daily care of patients. These diagnostic interviews were not conducted using structured interviews. Rather, we wanted clinicians to assess patients as they normally would, again increasing the generalizability of results and helping us better understand how DSM-5 might perform out in the “real world.” We anticipate that findings from the DSM-5 Field Trials will help address questions from the 13 work groups about their proposed revisions, such as whether the criteria are reliable and understandable…

DSM-5: How Reliable Is Reliable Enough?

by Helena Chmura Kraemer, David J. Kupfer, Diana E. Clarke, William E. Narrow, and Darrel A. Regier

American Journal of Psychiatry 2012 169:13-15.

[full text on-line]

…Reliability will be assessed using the intraclass kappa coefficient κI. For a categorical diagnosis with prevalence P, among subjects with an initial positive diagnosis, the probability of a second positive diagnosis is κI+P[1–κI], and among the remaining, it is P[1–κI]. The difference between these probabilities is κI. Thus κI=0 means that the first diagnosis has no predictive value for a second diagnosis, and κI=1 means that the first diagnosis is perfectly predictive of a second diagnosis…

From these results, to see a κIfor a DSM-5 diagnosis above 0.8 would be almost miraculous; to see κIbetween 0.6 and 0.8 would be cause for celebration. A realistic goal is κIbetween 0.4 and 0.6, while κIbetween 0.2 and 0.4 would be acceptable. We expect that the reliability [intraclass correlation coefficient] of DSM-5 dimensional measures will be larger, and we will aim for between 0.6 and 0.8 and accept between 0.4 and 0.6. The validity criteria in each case mirror those for reliability…

… followed by this response from Dr. Frances:

Two Fallacies Invalidate The DSM 5 Field Trials

Psychiatric Times

by Allen Frances

January 9, 2012The designer of the DSM 5 Field Trials has just written a telling commentary in the American Journal of Psychiatry. She makes two very basic errors that reveal the fundamental worthlessness of these Field Trials and their inability to provide any information that will be useful for DSM 5 decision making.

[1] The commentary states: “A realistic goal is a kappa between 0.4 and 0.6, while a kappa between 0.2 and 0.4 would be acceptable.” This is simply incorrect and flies in the face of all traditional standards of what is considered ‘acceptable’ diagnostic agreement among clinicians. Clearly, the commentary is attempting to greatly lower our expectations about the levels of reliability that were achieved in the field trials- to soften us up to the likely bad news that the DSM 5 proposals are unreliable. Unable to clear the historic bar of reasonable reliability, it appears that DSM 5 is choosing to drastically lower that bar – what was previously seen as clearly unacceptable is now being accepted. Kappa is a statistic that measures agreement among raters, corrected for chance agreement. Historically, kappas above 0.8 are considered good, above 0.6 fair, and under 0.6 poor. Before this AJP commentary, no one has ever felt comfortable endorsing kappas so low as 0.2-0.4. As a comparison, the personality section in DSM III was widely derided when its kappas were around 0.5. A kappa between 0.2-0.4 comes dangerously close to no agreement. ‘Accepting’ such low levels is a blatant fudge factor – lowering standards in this drastic way cheapens the currency of diagnosis and defeats the whole purpose of providing diagnostic criteria. Why does this matter? Good reliability does not guarantee validity or utility – human beings often agree very well on things that are dead wrong. But poor reliability is a certain sign of very deep trouble. If mental health clinicians cannot agree on a diagnosis, it is essentially worthless. The low reliability of DSM 5 presaged in the AJP commentary confirms fears that its criteria sets are so ambiguously written and difficult to interpret that they will be a serious obstacle to clinical practice and research. We will be returning to the wild west of idiosyncratic diagnostic practice that was the bane of psychiatry before DSM III..

[2] The commentary also states: “one contentious issue is whether it is important that the prevalence for diagnoses based on proposed criteria for DSM-5 match the prevalence for the corresponding DSM-IV diagnoses” …. “to require that the prevalence remain unchanged is to require that any existing difference between true and DSM-IV prevalence be reproduced in DSM-5. Any effort to improve the sensitivity of DSM-IV criteria will result in higher prevalence rates, and any effort to improve the specificity of DSM-IV criteria will result in lower prevalence rates. Thus, there are no specific expectations about the prevalence of disorders in DSM-5.” This is also a fudge. For completely unexplained and puzzling reasons, the DSM 5 field trials failed to measure the impact of its proposals on rates of disorder. These quotes in the commentary are an attempt to justify this fatal flaw in design. The contention is that we have no way of knowing what true rates of a given diagnosis should be – so why bother to measure what will be the likely impact on rates of the DSM 5 proposals. If rates double under DSM 5, the assumption will be that it is picking up previous false negatives with no need to worry about the risks of creating an army of new false positives…

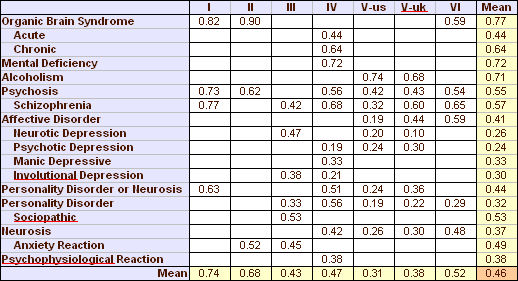

A Re-analysis of the Reliability of Psychiatric Diagnosis

By ROBERT L. SPITZER and JOSEPH L. FLEISS

British Journal of Psychiatry. 1974 125:341-347.

[reformatted][0.46 is the Mean of all values]]

Here’s a frequency distribution of all of the Kappa values in Spitzer’s table from the six studies…

And here are the two versions of the interpretation of Kappa from Dr. Kraemer’s and Dr. Frances’ articles in January of this year [above]…

| Kappa | ||||||||||

| <0.20 | >0.20 & <0.40 | >0.40 & <0.60 | >0.60 & <0.80 | >0.80 | ||||||

| Kraemer et al | negative | acceptable | realistic | celebration | miraculous | |||||

| Frances | negative | ~ no agreement | poor | fair | good | |||||

Ongoing news from the APA http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/2012/05/06/field-tests-for-revised-psychiatric-guide-reveal-reliability-problems-for-two-major-diagnoses/

Just as I’ve thought, inter-rater consistency for psychiatric diagnosis other than organic brain syndrome and alcoholism has always been cr*p.

FYI

Acad Psychiatry. 2012 Mar 1;36(2):129-32.

A comparison of psychiatry and internal medicine: a bibliometric study.

Stone K, Whitham EA, Ghaemi SN.

CONCLUSION: Psychiatric journals publish more biological studies than internal-medicine journals. This tendency may influence psychiatric education and practice in a biological direction, with less attention to psychosocial or clinical approaches to psychiatry.

Jamzo, that is an absolutely remarkable fact…

Resources are directed to rationalizing biological psychiatry rather than effective psychiatry.