Randomized controlled trial of interventions for young people at ultra-high risk of psychosis: twelve-month outcome.

by McGorry PD, Nelson B, Phillips LJ, Yuen HP, Francey SM, Thampi A, Berger GE, Amminger GP, Simmons MB, Kelly D, Thompson AD, and Yung AR.

Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2012 Nov 27. [Epub ahead of print]

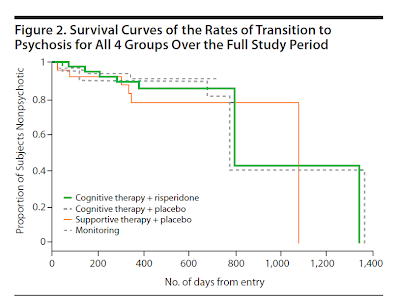

OBJECTIVE: The ultra-high risk clinical phenotype is associated with substantial distress and functional impairment and confers a greatly enhanced risk for transition to full-threshold psychosis. A range of interventions aimed at relieving current symptoms and functional impairment and reducing the risk of transition to psychosis has shown promising results, but the optimal type and sequence of intervention remain to be established. The aim of this study was to determine which intervention was most effective at preventing transition to psychosis: cognitive therapy plus low-dose risperidone, cognitive therapy plus placebo, or supportive therapy plus placebo.METHOD: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled 12-month trial of low-dose risperidone, cognitive therapy, or supportive therapy was conducted in a cohort of 115 clients of the Personal Assessment and Crisis Evaluation Clinic, a specialized service for young people at ultra-high risk of psychosis located in Melbourne, Australia. Recruitment commenced in August 2000 and ended in May 2006. The primary outcome measure was transition to full-threshold psychosis, defined a priori as frank psychotic symptoms occurring at least daily for 1 week or more and assessed using the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States. Secondary outcome measures were psychiatric symptoms, psychosocial functioning, and quality of life.RESULTS: The estimated 12-month transition rates were as follows: cognitive therapy + risperidone, 10.7%; cognitive therapy + placebo, 9.6%; and supportive therapy + placebo, 21.8%. While there were no statistically significant differences between the 3 groups in transition rates (log-rank test P = .60), all 3 groups improved substantially during the trial, particularly in terms of negative symptoms and overall functioning.CONCLUSIONS: The lower than expected, essentially equivalent transition rates in all 3 groups fail to provide support for the first-line use of antipsychotic medications in patients at ultra-high risk of psychosis, and an initial approach with supportive therapy is likely to be effective and carries fewer risks.

The evidence is adding up that the idea that one can use a premorbid clinical diagnostic assessment to accurately predict the subsequent development of Schizophrenia hasn’t panned out. One has to wonder why the DSM-5 Task Force thought it was anything more than speculative and stuck with the idea until the Field Trials in spite of a loud outcry, an outcry ultimately joined by the Australian group that was primarily involved in studying the question. Or why Dr. Insel would make it a centerpiece of a speech in Europe a year ago about leading edge discoveries. It looks to me like they were just desperate to have something to add to their manual to make up for having nothing much new to say about the progress in psychiatric diagnosis since 1994. In fact, our core diagnoses haven’t really changed all that much since Kraepelin a century ago. And Eugene Bleuler [who coined the term Schizophrenia] described this premorbid personality around the same time, saying that it was not specific enough for prediction.

Anything McGorry has claimed is worth pursuing… if only for the laughs you’ll get out of it.

Amen to your call to include the Rorschach to investigate early subtle signs of thought disorder and inaccurate perception in schizophrenia. The Rorschach remains the best tool to evaluate thinking and perception but is is sadly under-utilized today.

risk assessment = drug promotion

PR releases reported as News:Psychiatriy’s Propaganda Agenda

http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2012-12/uons-bii121712.php <-PR

http://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/breaking-news/bipolar-risk-could-be-found-earlier-study/story-fn3dxiwe-1226538218332 <-NEWS

but don't take my word for it…. Take the test and find out exactly how crazy you are….

http://www.blackdoginstitute.org.au/public/bipolardisorder/self-test.cfm

🙂

Here it comes, now that is appears there is an issue with Autism/Aspergers with the shooter in Conn, this quick fix mentality of “we need to fix these kids, get them on meds, that will avoid violence and personality problems.”

God, society is so stupid.

McGorry and his DRUG THE KIDS “preventative” intervention via antipsychotics is the heart of FIRST DO NO HARM– which in my opinion means “do not medicate children with antipsychotics full of side effects such as weight gain, diabetes, metabolic syndrome” just to make yourself feel better—Fuller Torrey must love this guy.

another one – see how the PR fiction is promoted as scientific truth…

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2012/12/121217102649.htm

NY & LA Times next…..

McGorry conflict of interest:

http://smh.com.au/national/mcgorry-accused-of-conflict-of-interest-20110806-1igxd.html

And after the shift of Government $$ from Better Health (psychology/counciling services, now only 6-10 sessionss per year), you look into the other sources of funding for Headspace and EPPIC you find ….. Pharma. Surprise, surprise!!!

From Fox News is an example of the coming fallout:

http://www.foxnews.com/health/2012/12/17/dr-manny-dont-jump-to-hasty-conclusions-about-newton-shooter/

Cosh guns not people!

Rorschach and TAT? Really? I doubt they would be helpful in reliably further predicting psychoses in populations being studied. I would like to see a comparison between the predictive power of the Rorschach or TAT vs. other psychometrics/diagnostics vs. nothing before I would really entertain this.

Nathan: You are uninformed. Please do a literature search on this issue.

Tom: I have. I haven’t seen anything convincing. The Rorschach cannot meaningfully predict much of anything, let alone sensitive enough to pick up meaningful differences among the identified cohort of folks that could be predicted to be given a schizophrenia diagnosis. Given the decreasing reliability in diagnoses of psychotic disorders, the poor inter-rater reliability of Rorschach scoring, the “norms” of such tests come from a meaningfully different population than the people who take take the test now, a strong critique or the notions that statistical norms of thought equate with health and deviations from norms equate disorder, I really am not convinced to the extent these tests can be helpful ( at least beyond any other more commonly used diagnostic too)l for the given question asked. I guess these tests can be helpful in identifying thought disorders (though you don’t need these tests to do that), in the context being discussed, people with “high risk” for psychosis that can be predicted to be more likely to develop persistent psychoses,have already been identified. What this means can be debated, though I actually think a bigger factor in predicting the chronicity of psychoses in folks with high functional impairment and distress is the preventative and unending managed use of anti-psychotic medication.

Expanding borders in psychiatry: embedded reporting from the 8th International Conference on Early Psychosis

http://somatosphere.net/2012/12/expanding-borders-in-psychiatry-embedded-reporting-from-the-8th-international-conference-on-early-psychosis.html

Jamzo,

How did you become aware of that link?

preventative CBT may not work for psychosis, but does appear to work for depression and anxiety

see refs. here http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mental_disorder#Research

From May 2012 about Dr. David Kupfer at the APA Annual Meeting in Philadeplphia

http://thoughtbroadcast.com/2012/05/12/is-the-joke-on-me/

“On Sunday, David Kupfer of the University of Pittsburgh (and task force chair of the forthcoming DSM-5) gave a talk on “Rethinking Bipolar Disorder.” The room—a cavernous hall at the Pennsylvania Convention Center—was packed. Every chair was filled, while scores of attendees stood in the back or sat on the floor, listening with rapt attention. The talk itself was a discussion of “where we need to go” in the management of bipolar disorder in the future. Dr Kupfer described a new view of bipolar disorder as a chronic, multifactorial disorder involving not just mood lability and extremes of behavior, but also endocrine, inflammatory, neurophysiologic, and metabolic processes that deserve our attention as well. He emphasized the fact that in between mood episodes, and even before they develop, there are a range of “dysfunctional symptom domains”—involving emotions, cognition, sleep, physical symptoms, and others—that we psychiatrists should be aware of. He also introduced a potential way to “stage” development of bipolar disorder (similar to the way doctors stage tumors), suggesting that people at early stages might benefit from prophylactic psychiatric intervention.”

Dr. Melissa DelBello, who is on the research workgroup (one of three workgroups within the AACAP Back to Project Future initiative meant to map out directions for the next ten years) led by Dr. Neal Ryan:

Preventative strategies for early-onset bipolar disorder: towards a clinical staging model.

Authors

McNamara RK, Nandagopal JJ, Strakowski SM, DelBello MP.

Journal

CNS Drugs. 2010 Dec;24(12):983-96. doi: 10.2165/11539700-000000000-00000.

Affiliation

Department of Psychiatry, Division of Bipolar Disorders Research, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA.

Abstract

Bipolar disorder is a chronic and typically recurring illness with significant psychosocial morbidity. Although the aetiological factors that contribute to the onset of mania, and by definition bipolar I disorder, are poorly understood, it most commonly occurs during the adolescent period. Putative risk factors for developing bipolar disorder include having a first-degree relative with a mood disorder, physical/sexual abuse and other psychosocial stressors, substance use disorders, psychostimulant and antidepressant medication exposure and omega-3 fatty acid deficiency. Prominent prodromal clinical features include episodic symptoms of depression, anxiety, hypomania, anger/irritability and disturbances in sleep and attention. Because prodromal mood symptoms precede the onset of mania by an average of 10 years, and there is low specificity of risk factors and prodromal features for mania, interventions initiated prior to onset of the disorder (primary prevention) or early in the course of the disorder (early or secondary prevention) must be safe and well tolerated upon long-term exposure. Indeed, antidepressant and psychostimulant medications may precipitate the onset of mania. Although mood stabilizers and atypical antipsychotic medications exhibit efficacy in youth with bipolar I disorder, their efficacy for the treatment of prodromal mood symptoms is largely unknown. Moreover, mood stabilizers and atypical antipsychotics are associated with prohibitive treatment-emergent adverse effects. In contrast, omega-3 fatty acids have neurotrophic and neuroprotective properties and have been found to be efficacious, safe and well tolerated in the treatment of manic and depressive symptoms in children and adolescents. Together, extant evidence endorses a clinical staging model in which subjects at elevated risk for developing mania are treated with safer interventions (i.e. omega-3 fatty acids, family-focused therapy) in the prodromal phase, followed by pharmacological agents with potential adverse effects for nonresponsive cases and secondary prevention. This approach warrants evaluation in prospective longitudinal trials in youth determined to be at ultra-high risk for bipolar I disorder.

PMID 21090835

Dr. Kiki Chang, also part of the same workgroup with Dr. Melissa DelBello:

Prevention of pediatric bipolar disorder: integration of neurobiological and psychosocial processes.

AuthorsChang K, et al.

Journal

Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006 Dec;1094:235-47.

Affiliation

Pediatric Bipolar Disorders Program, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California, USA.

Abstract

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a prevalent condition in the United States that typically begins before the age of 18 years and is being increasingly recognized in children and adolescents. Despite great efforts in discovering more effective treatments for BD, it remains a difficult-to-treat condition with high morbidity and mortality. Therefore, it appears prudent to focus energies into developing interventions designed to prevent individuals from ever fully developing BD. Such interventions early in the development of the illness might prevent inappropriate interventions that may worsen or hasten development of BD, delay the onset of first manic episode, and/or prevent development of full BD. Studies of populations at high-risk for BD development have indicated that children with strong family histories of BD, who are themselves experiencing symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactive disorder (ADHD) and/or depression or have early mood dysregulation, may be experiencing prodromal states of BD. Understanding the neurobiological and genetic underpinnings that create risk for BD development would help with more accurate identification of this prodromal population, which could then lead to suitable preventative interventions. Such interventions could be pharmacologic or psychosocial in nature. Reductions in stress and increases in coping abilities through psychosocial interventions could decrease the chance of a future manic episode. Similarly, psychotropic medications may decrease negative sequelae of stress and have potential for neuroprotective and neurogenic effects that may contribute to prevention of fully expressed BD. Further research into the biologic and environmental mechanisms of BD development as well as controlled early intervention studies are needed to ameliorate this significant public health problem.

PMID 17347355

Dr. Daniel Pine, also part of the same workgroup:

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/29/magazine/29preschool-t.html

“ “One of the most important mental-health discoveries of the past 10 to 20 years has been that chronic mental illnesses are predominantly illnesses of the young,” says Daniel Pine, chief of the emotion-and-development branch in the Mood and Anxiety Disorders Program of the National Institute of Mental Health. “

“ “There was this big worry that once you labeled it, you actually had it,” explains Neal Ryan, a professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh.”

“ “We realized, Gee, maybe we better look more carefully at preschool, too,” Pine says. “And that’s where we are today. The issue of diagnosis of depression in preschoolers is being looked at very carefully right now.””

“”“We don’t like to diagnose depression in a preschooler,” says Mary O’Connor, from U.C.L.A. “These kids are still forming, so we’re more likely to call it a mood disorder N.O.S. That’s just the way we think of it here.”

But this way of thinking frustrates Luby and Egger, who say they fear that if a depressed child isn’t given the proper diagnosis, he can’t get appropriate treatment. You wouldn’t use the vague term “heart condition,” they argue, to describe a specific form of cardiac arrhythmia. “Why do we call depression in older children a ‘disorder,’ but with young children we just call it a ‘risk factor’ or ‘phase’?” Egger asks. Is it right that rather than treat children for depression, clinicians wait and see what might happen three or four years down the road?”

Dr. Neal Ryan, leader of the workgroup:

http://apps.psychiatry.ufl.edu/Newsletters/Archive/Ryan/ryan.html

“Q: Do you think the prescription of antidepressants by family MDs and pediatricians are part of the problem?

A:No. I think it is critical that we find treatments that primary doctors can use. They are the 1st line of therapy for uncomplicated depression.”