There are a lot of words like Courage, Bravery, Cowardice, or Heroism that we use as nouns, but are really closer to adverbs describing actions rather than some intrinsic entity – some person-place-or-thing [as nouns were described by our elementary school teachers]. I’m not trying to be a grammarian here. I’m aiming at talking about another word, Resiliency. We all know that in the face of a given traumatic event, some people leave the experience perhaps shaken, but otherwise intact. Yet others may have lifelong symptoms called post-traumatic stress disorder. In the past, this difference might be described as weak versus strong, but hopefully we’re beyond that at this point in history. So there’s a new word, Resiliency, that’s in vogue to describe this difference. Again, it’s a word that can only be defined in terms of behavior, action. It’s not really a noun of the kind sweet old Ms. Bell taught me about. Those with Resiliency don’t get traumatized and those without Resiliency do get traumatized. In rhetoric, that’s called a tautology – a word that is its own definition.

Can you teach Courage, Bravery, or Heroism? We sure spend a lot of time trying. It’s called Basic Training, or Ranger School, or Special Forces Training. These are not simply didactic courses but rather rely on experiential learning. People are taught through repeated experience how to maintain control of rational thought in the face of grave danger and uncertainty; how to be simultaneously hypervigilant and emotionally detached when presented with the fog of war. Can you teach Resiliency? I expect you can teach people to be less prone to being traumatized. But the hallmark of a traumatic experience is to be unexpectedly faced with a dire situation that one has no tools to deal with, and in the face of rapidly escalating and overwhelming emotion, the mind shuts down, dissociates, whatever you want to call that process the films try to show by putting vasoline on the lens, changing the lighting to eerie, and garbling the sound. I expect there’s a limit on how much of that can actually be taught.

I originally encountered this term from students when teaching about PTSD. I couldn’t see the relevance since I was talking about patients who already had PTSD, but I went to the literature to see what they were reading. That was a few years back, but most of what I found was more wishful that "evidence-based." Read this Wikipedia article to see what I mean. I don’t question the phenomena being described. I just don’t see how the long known observation relates to the topic of what to do with the thought.

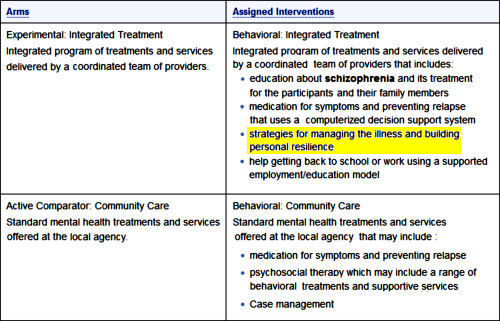

Now I see Resiliency in a new context, as part of the RAISE ETP Project [Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode]:

They are referring to a specific structuralized program called Individual Resiliency Training [IRT] outlined in the linked document [974 pages]. This was apparently created for this program specifically, and is the part that’s new, supplementing the traditional triad of education, medication, and vocational counselling already widely used. It sounds like a good idea. But we don’t yet know if it is value-added, since the results of the RAISE ETP Project are not yet available. And since this program may soon go live on a major scale through SAMHSA Block Grant funding, it’s something we need to know already.

Have also scanned it. Reminds me of several modules in the past that have fallen flat. Much of this is after all supportive psychotherapy with more explicit CBT elements. Regardless of the clinical trial results, none of this will happen as long as care for people with psychosis is reduced to hospitalizations for dangerousness and 10-15 minute “med checks” or a quick transfer to the county jail.

This module in many ways represents state of the art care when combined with the medical side. You need systems that are funded as centers of excellence and adequately staffed to provide care. A psychiatrist seeing 20 patients a day with no clerical or administrative help, much less adequate therapy support will never implement this program. The managed care company employing that psychiatrist has already made the decision that brief visits for medication is all that they will do and will not deploy a more state of the art program either.

One of the great losses of replacing senior clinicians with full time administrators is the loss of interest in state of the art care sacrificed for care that the company can make a maximum profit from.

The resiliency training appears to be based on Positive Psychology.

A critic: http://blogs.plos.org/mindthebrain/2013/08/21/positive-psychology-is-mainly-for-rich-white-people/

I agree with George Dawson. This Individualized Resilience Training (IRT) looks like a dressed-up, manualized version of training for coping skills plus supportive-psychoeducational therapy, plus case management. What’s remarkable is that it is presented as something new. Everything is discussed in terms of modules and stages, with performance objectives.

When they attempt to specify what Resilience is, they descend into bathos:

“This module helps the client get oriented to what recovery is and to the concept of resilience. The client is asked to consider the concept of resilience and how he or she defines it. The goal is to instill hope and have the client realize that resilience is a characteristic that can help him or her overcome an initial psychotic episode… The heart of IRT is the setting and pursuing of personally meaningful goals… ” (Page 7, Module 2) “In addition to basic education about psychosis, this module revisits the concept of resilience. The client is asked to define resilience in his or her own words and to consider how resilience can be incorporated into his or her treatment. Finally, the client is introduced to “resiliency stories,” which refer to difficult experiences that people have been able to overcome, and the client’s own resilience in the face of challenges is explored. Such stories help clients to discover resilient qualities within themselves, how these qualities have enabled them deal with problems in the past, and how they may help them overcome the challenges they currently face.” (Page 8, Module 3). This would better be discussed with patients recovering from an initial psychotic episode in terms of practical coping goals. Introducing the metaphysical construct of resiliency adds nothing and risks demoralizing patients who will discover that they don’t possess it.

The patient-centered goals are all desirable but, as George Dawson says, where will the funding come from to do all that is described? The 7 initial, basic modules alone are projected to need 4-6 months for completion. And who will supervise the behaviorally-trained workers who administer the modules? As Max Weber and Karl Jaspers might have said, there is no Verstehen anywhere in sight.

Moreover, the description smacks of armchair planning of services for nice clients by nice mental health administrators. Will they do a demonstration trial within the Los Angeles County jail?

I do not understand these comments. We criticize the lack of services available but when an attempt is made to establish intensive services, there is a complaint that it won’t be supported with funding. Isn’t this a chicken and egg kind of problem? You need to start somewhere.

IRT is not done by psychiatrists. The psychiatrist is a part of a multidisciplinary team that meets frequently and support for these “non-billable” times is what I believe is supported by a block grant model of funding. I am not a financial expert but I do work with block grant funding and this has allowed me to avoid having to work in the “15 minute” model.

I understand1BOM’s point that they are pushing a novel treatment before the data is out but it is not entirely novel. Wellness management has been studied with some reported benefit in the past. IRT pulled in from CBT-p and while I understand there is dispute as to whether this can be considered evidenced based, I see SAMSHA trying to provide financial support for demonstration projects so that we can continue to learn whether enhanced services at the beginning may improve long term outcome.

My own read of first episode interventions worldwide is that early engagement – of any kind – seems to correlate with improved outcomes. Offering services that de-emphasize the reliance on neuroleptics as the primary intervention seems like a good thing for many reasons that in my opinion are supported by evidence (see the Finnish Open Dialogue studies as well as McGorry).

I don’t understand your comment, Sandra. No one is arguing against providing comprehensive services. In this case, however, the conceptual model rests on a pretentious and ill-advised metaphysical construct they are calling resilience. There is a good chance it will backfire for many patients. Plus, the program with all its modules is overly prescriptive – it’s micromanagement, in fact. For SAMHSA to fly this kite just for first episode psychosis patients is a feel-good stopgap. What SAMHSA really needs to do is work for adequate funding, staffing, and facilities across the board in the public mental health sector, and then to step away from micromanagement.

Sandy,

I’m all over the place saying that I’m for this program. I actually want it to work, endure. And with me, my comments aren’t about the invariable psychiatrist vs other conflicts. There aren’t enough psychiatrists on the planet to do what needs doing. I don’t even mind using the SAMHSA funds. Any port in the storm, I always say.

Years ago, when I had a job sort of like yours, I collected a cadre of people who were just naturally good at working with these patients and their educational paths were immaterial. They just knew how to engage these patients. My problem with the IRT isn’t that it exists, or even the word “resiliency,” it’s the content. I’m going to write about what I think [because that’s what I do], but this is outside my usual topic area, not intended to be destructive [and happens to have revived some of my old passion for these patients]. I am one of those people I’m talking about who just knew how to engage those patients and feel like I’d like to pass on what I can of that.

I even agree that anything is better than nothing. But they have gotten the funding to even go that one better. I’m not in attack mode about RAISE, but I do want it to work. Like Dr. Carroll, I’m worried that if that IRT manual is followed too closely, it will distance these patients rather than engage them. But that’ll be coming soon and you can have a go at the whole criticism. If it’s “unconstructive,” let me know. You’re the front liner in this dialog…

I am not trying to be critical in my comments and I am sorry if it comes off that way. I am just trying to understand the comments. Dr. Carroll’s response clarifies it for me and I agree with his comment for the need to just generally increase funding. I generally understand and agree with what you have been saying.

This is my main area of interest. I am a RAISE psychiatrist in the NAVIGATE arm. I can not speak for the study team since I do not have access to the data. I can only speak from the experience of being in the trenches. During the time I participated, I also studied and trained in the Open Dialogue paradigm and other FEP programs. As you know, I have also been looking at our general approach to treating people who are psychotic. A few weeks ago, I went to a seminar with Bertram Karon who recommends psychoanalysis as a first line treatment for schizophrenia. Yesterday, Courtenay Harding who did a remarkable longitudinal study of schizophrenia – 30 year outcomes of the people who did not respond to chlorpromazine in its first wave of use in VT but entered into a novel and progressive rehab program. Over 2/3 were recovered in her study. A lot of what they did was tell people they could recover and then they worked to put the tools and framework in place to give them half a chance at doing just that.

I think this thing we call schizophrenia is heterogeneous and I am most inclined to the needs adapted approaches from Scandinavia. There is a big trial going on now in NYC called parachute and I hope we are hear more about it in years to come.

But we live in an evidenced based world. If you go too far from the line of science based approaches to helping people, you risk being dismissed by your colleagues. I suspect the manualized approaches will be very helpful for some but not all and just getting the person into the room is a huge challenge. I also suspect that like everything in our world today, this too will be hyped and oversold (I think that is what you are addressing). However, these manuals contain some useful guidelines on how to talk to people about psychosis other than just encouraging them to take their medications. The program focuses on getting back to work and to school and there is a good support in the research that this is an important thing to do. Even if we hire more people to do the work, we need to give them some idea of what to do once they have their job and these manuals can help with that. In my experience, DBT worked that way. At first it was applied rather rigidly but now many of the concepts have worked their way into many aspects of what we do and the tools we try to give people to help them recover.

However, if this increases resources and attention, I think that many well meaning and caring people will use the manual but end up not following it to the T; some of them are bound to look up and see the human being sitting in the room.

Speaking only for myself, if I were in a rehab program getting lectures about “resilience” and being shown examples of people who supposedly were more “resilient” than I am, I would probably end up biting somebody.

But then I looked into Positive Psychology and got an allergic reaction to it. Didn’t care for CBT either. I simply hate being told what to think.

Here is a story of resilience and bullshit from the Guardian with some added information from an article in the L.A. Times:

It was autumn, and Patricia van Tighem and her husband, Trevor Janz, were hiking in Waterton Lakes National Park, Canada. As they passed into a dense pine forest, Patricia had a sense of foreboding. Something was not right. Trevor called her paranoid, and they resumed their climb. It was a popular trail. There seemed no reason for concern. Yet as they came into view of a waterfall, Patricia stopped again. An awful smell hit her, but Trevor dismissed it. A bighorn sheep had died just off the trail and though she didn’t know it, she could smell its decomposing body. Patricia worried aloud about bears, but Trevor’s enthusiasm won out (emphasis added) and they pressed on up the trail.

Trevor rushed ahead, eager as always to plunge onward. He disappeared round a bend and Patricia hurried to follow. But as she came within sight of him, something was out of place. It took a moment before she could comprehend what she was seeing. Trevor was down and a bear’s jaws were around his leg…

The bear charged Patricia so fast that she could scarcely take it in. Their eyes met for a moment. Then the bear took her head in its mouth and began chewing. She could feel its teeth scraping across her skull, ripping away her eye and half of her face. Patricia thought of her mother and of all the people who would be destroyed by her death, and she reached up and twisted the huge black nose before her. The bear barked and stood aside. It began pacing in front of her. Patricia played dead….

Trevor was disfigured, too*, his head and face crisscrossed with stitches, his jaw broken, his leg ripped open and sewn back together. And yet, as they left the hospital that day, he was singing, despite the fact that his jaw was wired shut. Again and again, he said he felt lucky and grateful to be alive. One evening, he smuggled a wheelchair to Patricia’s room and sneaked her out of the ward to see the beautiful view. That night he said he wanted to get out of the hospital and go ice climbing. In his mind, he was rapidly moving on from the experience….

It had to be resilience, of course, such behavior couldn’t be denial or overcompensating, because those aren’t financially rewarding buzzwords.

She and Trevor sought help from a psychotherapist. Trevor voiced his frustration with his wife. They had tried to go on a hike together, but after 15 minutes Patricia was ill with trepidation and had to turn back. That night, she had terrifying dreams…

Trevor had nightmares sometimes, too, but his response was not to think about it. He just put it out of his mind. Psychiatrist George Vaillant, in his Study Of Adult Development, found that this type of suppression was straightforward, practical, and it worked. “Of all the coping mechanisms,” he wrote, “suppression alters the world the least and best accepts the terms life offers.”…

Trevor forced this hard-nosed logic to dominate over emotion, telling his wife, “We won’t be attacked again, Trish. We’re predisastered.”…

This is logic? Sounds like superstition and an inexcusably glib response to his wife’s feelings.

Although they had survived almost the same experience, the differences in their responses grew greater over time.

But they had not survived “almost the same experience”.* From the L.A. Times (announcing her suicide):

Her facial injuries were extensive. The left side of her face was nearly destroyed, her cheekbone absent, her left eye blind, the eyelids gone. The back of her scalp was missing. “I feel sick to my stomach,” she wrote about looking in the hospital mirror. “What I see isn’t even me.”

Her husband’s injuries were not as disfiguring. The third-year medical student’s jaw and nose had been broken but his spirit was still intact.

And his face was also intact, I might add. But here’s the kicker:

Patricia’s temperament actually might have prevented the accident. When they were going up the trail, she had sensed something. She smelled the dead sheep and knew it was a warning signal. She was consciously afraid of bears at that moment. (The grizzly was feeding on the dead sheep and attacked them in an attempt to protect its find.) Left to her own devices, she might well have turned back. Instead, Trevor’s boldness won out. His personality proved much more resilient in the aftermath. And Patricia’s apprehension, the very sensitivity that might have saved them, became her greatest liability in the years to come.

What else could it be? She was “sensitive,” he clearly was not. By this logic, jerks are at the pinnacle of mental wellness and “sensitive” people are just a mess. She was cautious, he called her “paranoid”. He was resilient; she was not. Pay no attention to the woman with the disfigured face behind the curtain of her husband’s “resilience, “suppression,” apparent lack of feelings of responsibility or regret for the attack, and his impatience with his wife’s condition. What a fucking prince.

http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2012/nov/09/life-after-near-death

http://articles.latimes.com/2005/dec/25/local/me-vantighem25

“Resilience” is tautological. Wouldn’t it make more sense to look at social support or its absence?