Collaborative Care is a specific type of integrated care developed at the University of Washington that treats common mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety that require systematic follow-up due to their persistent nature. Based on principles of effective chronic illness care, Collaborative Care focuses on defined patient populations tracked in a registry, measurement-based practice and treatment to target. Trained primary care providers and embedded behavioral health professionals provide evidence-based medication or psychosocial treatments, supported by regular psychiatric case consultation and treatment adjustment for patients who are not improving as expected.

Collaborative Care originated in a research culture and has now been tested in more than 80 randomized controlled trials in the US and abroad. Several recent meta-analyses make it clear that Collaborative Care consistently improves on care as usual. It leads to better patient outcomes, better patient and provider satisfaction, improved functioning, and reductions in health care costs, achieving the Triple Aim of health care reform. Collaborative Care necessitates a practice change on multiple levels and is nothing short of a new way to practice medicine, but it works. The bottom line is that patients get better.

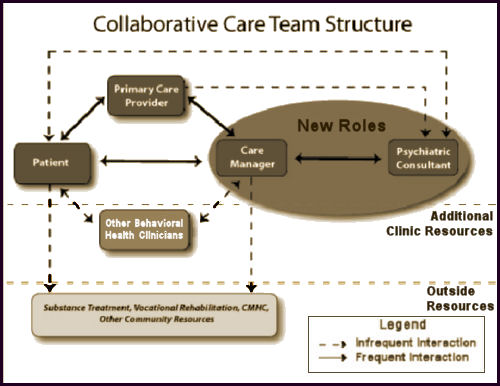

The great irony of this legacy passed on to us from the PHARMA tarnished KOLs who sold out psychiatry long ago is that it forces anyone participating in it to do the very thing that everyone is complaining about – see medication as the first line treatment of mental illness and overprescribe. To even amplify the irony, this model is essentially supported and encouraged by the people who criticize the bio-bio-bio models the most [see the rise and ??? of the guild…]. The KOLs and PHARMAs of the decades bracketing the century mark succeeded in reducing psychiatry to pill-pushing for their profit and this is what they’ve passed along to us – now encoded as Collaborative Care. What other Behavioral Health Clinicians haven’t quite figured out is that they are on a dotted line too, and are already feeling their future dwindling along with psychiatry and headed for a similar fate. Unfortunately, for all concerned, all of this actually hinges on the business-fication of the word "Care," and is unlikely to change until society rediscovers other meanings of the word. Like the bumper sticker in the 1980s prophetically said, "Managed Care is Neither!"

The Cochrane Collaborationby Janine Archer, Peter Bower, Simon Gilbody, Karina Lovell, David Richards, Linda Gask, Chris Dickens, and Peter Coventry17 OCT 2012

Background: Common mental health problems, such as depression and anxiety, are estimated to affect up to 15% of the UK population at any one time, and health care systems worldwide need to implement interventions to reduce the impact and burden of these conditions. Collaborative care is a complex intervention based on chronic disease management models that may be effective in the management of these common mental health problems.Objectives: To assess the effectiveness of collaborative care for patients with depression or anxiety.Search methods: We searched the following databases to February 2012: The Cochrane Collaboration Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group [CCDAN] trials registers [CCDANCTR-References and CCDANCTR-Studies] which include relevant randomised controlled trials [RCTs] from MEDLINE [1950 to present], EMBASE [1974 to present], PsycINFO [1967 to present] and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials [CENTRAL, all years]; the World Health Organization [WHO] trials portal [ICTRP]; ClinicalTrials.gov; and CINAHL [to November 2010 only]. We screened the reference lists of reports of all included studies and published systematic reviews for reports of additional studies. Selection criteria: Randomised controlled trials [RCTs] of collaborative care for participants of all ages with depression or anxiety.Data collection and analysis: Two independent researchers extracted data using a standardised data extraction sheet. Two independent researchers made ‘Risk of bias’ assessments using criteria from The Cochrane Collaboration. We combined continuous measures of outcome using standardised mean differences [SMDs] with 95% confidence intervals [CIs]. We combined dichotomous measures using risk ratios [RRs] with 95% CIs. Sensitivity analyses tested the robustness of the results.Main results: We included seventy-nine RCTs [including 90 relevant comparisons] involving 24,308 participants in the review. Studies varied in terms of risk of bias. The results of primary analyses demonstrated significantly greater improvement in depression outcomes for adults with depression treated with the collaborative care model in the short-term [SMD -0.34, 95% CI -0.41 to -0.27; RR 1.32, 95% CI 1.22 to 1.43], medium-term [SMD -0.28, 95% CI -0.41 to -0.15; RR 1.31, 95% CI 1.17 to 1.48], and long-term [SMD -0.35, 95% CI -0.46 to -0.24; RR 1.29, 95% CI 1.18 to 1.41]. However, these significant benefits were not demonstrated into the very long-term [RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.27]. The results also demonstrated significantly greater improvement in anxiety outcomes for adults with anxiety treated with the collaborative care model in the short-term [SMD -0.30, 95% CI -0.44 to -0.17; RR 1.50, 95% CI 1.21 to 1.87], medium-term [SMD -0.33, 95% CI -0.47 to -0.19; RR 1.41, 95% CI 1.18 to 1.69], and long-term [SMD -0.20, 95% CI -0.34 to -0.06; RR 1.26, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.42]. No comparisons examined the effects of the intervention on anxiety outcomes in the very long-term. There was evidence of benefit in secondary outcomes including medication use, mental health quality of life, and patient satisfaction, although there was less evidence of benefit in physical quality of life.Authors’ conclusions: Collaborative care is associated with significant improvement in depression and anxiety outcomes compared with usual care, and represents a useful addition to clinical pathways for adult patients with depression and anxiety.

The Cochrane Collaboration.by Siobhan Reilly, Claire Planner, Linda Gask, Mark Hann, Sarah Knowles, Benjamin Druss, and Helen Lester4 NOV 2013

Background: Collaborative care for severe mental illness [SMI] is a community-based intervention, which typically consists of a number of components. The intervention aims to improve the physical and/or mental health care of individuals with SMI.Objectives: To assess the effectiveness of collaborative care approaches in comparison with standard care for people with SMI who are living in the community. The primary outcome of interest was psychiatric admissions.Search methods: We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Specialised register in April 2011. The register is compiled from systematic searches of major databases, handsearches of relevant journals and conference proceedings. We also contacted 51 experts in the field of SMI and collaborative care.Selection criteria: Randomised controlled trials [RCTs] described as collaborative care by the trialists comparing any form of collaborative care with ‘standard care’ for adults [18+ years] living in the community with a diagnosis of SMI, defined as schizophrenia or other types of schizophrenia-like psychosis [e.g. schizophreniform and schizoaffective disorders], bipolar affective disorder or other types of psychosis.Data collection and analysis: Two review authors worked independently to extract and quality assess data. For dichotomous data, we calculated the risk ratio [RR] with 95% confidence intervals [CIs] and we calculated mean differences [MD] with 95% CIs for continuous data. Risk of bias was assessed.Main results: We included one RCT [306 participants; US veterans with bipolar disorder I or II] in this review. We did not find any trials meeting our inclusion criteria that included people with schizophrenia. The trial provided data for one comparison: collaborative care versus standard care. All results are ‘low or very low quality evidence’.Data indicated that collaborative care reduced psychiatric admissions at year two in comparison to standard care [n = 306, 1 RCT, RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.99].The sensitivity analysis showed that the proportion of participants psychiatrically hospitalised was lower in the intervention group than the standard care group in year three: 28% compared to 38% [n = 330, 1 RCT, RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.99].In comparison to the standard care group, collaborative care significantly improved the Mental Health Component [MHC] of quality of life at the three-year follow-up, [n = 306, 1 RCT, MD 3.50, 95% CI 1.80 to 5.20]. The Physical Health Component [PHC] of the quality of life measure at the three-year follow-up did not differ significantly between groups [n = 306, 1 RCT, MD 0.50, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.91].Direct intervention [all-treatment] costs of collaborative care at the three-year follow-up did not differ significantly from standard care [n = 306, 1 RCT, MD -$2981.00, 95% CI $16934.93 to $10972.93]. The proportion of participants leaving the study early did not differ significantly between groups [n = 306, 1 RCT, RR 1.71, 95% CI 0.77 to 3.79]. There is no trial-based information regarding the effect of collaborative care for people with schizophrenia.No statistically significant differences were found between groups for number of deaths by suicide at three years [n = 330, 1 RCT, RR 0.34, 95% CI 0.01 to 8.32], or the number of participants that died from all other causes at three years [n = 330, 1 RCT, RR 1.54, 95% CI 0.65 to 3.66].Authors’ conclusions: The review did not identify any studies relevant to care of people with schizophrenia and hence there is no evidence available to determine if collaborative care is effective for people suffering from schizophrenia or schizophreniform disorders. There was however one trial at high risk of bias that suggests that collaborative care for US veterans with bipolar disorder may reduce psychiatric admissions at two years and improves quality of life [mental health component] at three years, however, on its own it is not sufficient for us to make any recommendations regarding its effectiveness. More large, well designed, conducted and reported trials are required before any clinical or policy making decisions can be made.

State medical boards can go after a doctor who prescribes without examining a patient. I don’t see how collabocare is qualitatively different in that respect.

If one believes in the validity of this idea, it is essentially conceding that a NP or generalist does just as good of a mental status examination as a psychiatrist. If that is really the case, we might as well just fold up the specialty and replace use with software (which is coming).

This Psych Times article is all rosy about collabocare:

http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/special-reports/depression-and-diabetes-improving-outcomes-through-collaborative-care

However, there is nothing magical here…in one case an antidepressant worked, and in another the patient was switched to another antidepressant that worked.

What the article fails to discuss is why it just wouldn’t have been better to refer to a psychiatrist from day one. We know the answer, and it has nothing to do with quality care.

If psychiatry embraces this I will conclude that we are more professionally masochistic than the internists who lead the pack in self-immolation.

A few key concepts with collaborative care:

1. The current movement is identical to the managed care movement in the 1980s. A loose coalition of researchers, business people, and politicians promote a completely political version of care and they are very good at it. Physicians don’t know what hit them and are easily overwhelmed.

2. Much “research” is generated to prove the political myth that physicians are money grubbers and that Fee-for-service is “no better than managed care”. The real science that was totally ignored was that the Peer Review Organizations failed to show that there was a significant amount of “overutilization” on a state by state basis using rigorously screened physician reviewers. The response was to largely disband the PROs and turn the review process over to for-profit companies.

3. The idea of “population based care” is promoted even though to this day – nobody knows what that means. There is no physician I know who is trained to take care of populations.

4. The Cochrane Reviews listed here show how little value this site has. In this case the anxiety and depression results are the equivalent of the early managed care designs. All of those managed care trials resulted in a precipitous drop in the quality of mental health care in this country and it was consistent with Ioannidis thesis that almost all published research is false. Why would this be any different? Because it is on the Cochrane site? The Cochrane site also seems to completely ignore the information on ACT teams, probably because it is a community psychiatry and not a business approach.

Other thoughts:

http://real-psychiatry.blogspot.com/search/label/collaborative%20care

The businessfication of medicine is a malignant force. The Bureau of Labor Statistics predicts a 24% increase in the number of managers in the next 10 years on top of the 300% increase over the past two decades. The real irony is that it is being sold as the scientific management of medicine – when it has nothing to do with science (or medicine) at all.

Had a nice conversation with a graduating resident the other day. He was excited about taking a position at a hospital system implementing this type of model. He said he would be interfacing with a bunch of satellite internal medicine practices and that telepsychiatry was a major piece of how this stuff will be implemented.

Telepsychiatry. There’s a telepsychiatrist at the mental health clinic up here in Appalachia. I see a lot of people who come to our clinic fleeing the the telepsychiatrist – and their conversations in our waiting room joking about the experience are really pretty funny.

Ask the excited resident how excited a cardiologist would be about trusting his cardiac exam. Then ask him why he would trust the mental status exam of a generalist. Then ask him if he is excited to eventually be replaced by a software algorithm.

Expert in human behavior doesn’t realize he’s being played for a fool. And as Dr. Dawson pointed doesn’t seem to mind the repeating past mistakes, which experts in human behavior should avoid.

As for me, I’m going with the advice of Roger Daltrey and ignoring the APA leadership. Won’t get fooled again.

My concerns follow the general theme of the comments. As I move through life I find Mickey’s past comments about people blaming behaviors on some passing comment made by a doctor in relation to their mental health to be more and more common.

I also deal with the reality that in my area most doctors’ offices are owned by hospitals and they are very revenue driven. This will mean that patients will see one more pill added to their daily medications and this will be reviewed in the typical four minute interaction with a doctor every 90 days where the doctor interrupts after less than 30 seconds.

Add to this trying to deal with people when you are not in a position of authority, and those in authority make excuses, and you have a very frustrating situation.

Mental health diagnosis and care is a mess in this country. People who need care are not receiving it and those who do not need it are being medicated because it is financially lucrative. We no longer know the mind set of the person driving next to us or the person sitting at the next desk. Then we wonder why we are in the middle of some rage incident or a person is so numb as to be non-responsive.

Steve Lucas

I don’t think the APA leadership support of this is financially motivated. I think it is ideologically motivated. Which in this case is worse, because if they had the financial interests of the group in mind (not to mention basic professionalism and the interest of individual patients) they wouldn’t support it. Lieberman, who posted the first video about this from APA, was a big fan of carving out a role for psychiatry under ACA because he was thoroughly committed to ACA politically and the idea of treating populations rather than patients.

Any APA involvement is generally either Big Tent politics, the usual researcher level conflict of interest (yes I am an expert in this area and here are my papers) or in some cases direct conflict of interest due to employer and position. That is my recollection of how we all ended up with managed care and there is no reason to expect that it will be any different with collaborative care.

I can’t help but note that the usual conflict of interest discussions on 1BOM pertain to Big Pharma. Managed care and now collaborative care COI is much more problematic. Anyone can choose not to prescribe a drug. Nobody gets a choice when your patient is thrown out of a hospital or not admitted because they are not “dangerous” enough. People can make up imaginary numbers about the toll of psychopharmaceuticals. Nobody even cares how many people die or are permanently disabled because they never get adequate treatment in the current system that is rationing care for mental illness and addictions.

That is no accident.

think about it for a second. What do politicians do: at the end of the day, what is popular easy and convenient. What is the APA? what are their basic responsibilities, but be a political system, well, so what do they do?

Again, what is popular easy and convenient. So if the recent statement at least 33,000 psychiatrists belong to theAPA, which I do not believe that statistic, then I guess we have a lot of people just practicing what is popular, easy and convenient.

Being a physician is not about quick decisions and solely making a buck. So if we are practicing simply what is easy and convenient,and not what is appropriate and responsible and often difficult, then I guess we are simply screwed. And as long as we allow people in positions of power and influence , whether they be colleagues or administrators or politicians and we allow this mindset to win, then we are screwed royally!

I think this is on the rank and file…if someone continues to belong and pay money to organizations that no longer represent their interests (and sometimes actively oppose, in the case of collabocare and MOC) simply out of loyalty or force of habit, there are consequences for failure to adapt. Why should those in power change anything as long as the checks keep rolling in? It’s pretty basic behaviorism. The only way that any of these organizations change as if members walk…only 15% belong to the AMA so there is a logical tipping point…I think we overrate the impact of these groups anyway…what do any of us know about the impact of the American Psychological Association and vice versa…these groups are really not that powerful unless you imagine they are.

I would see it as a standard American oligarchy. To me it is no different than showing up to vote for another Clinton or Bush. If the country can be run by a few people – any organization can.

My denomination fits this model. With a massive loss of members the leadership claims a moral victory and using endowment funds continue to receive those all important pay checks.

What is worse is that when good people try to engage in meaningful dialogue leadership simply stalls the whole process, often for years, until they claim the other side has given up on the process. Discussions on policy have become generational and when searching for outside intervention those challenging the process are declared unworthy.

While this is a political victory, this does not address the issues at hand.

Steve Lucas

I agree with the comment of Dr. Dawson…this is a problem with baby boomers in general…trust “labels” and throw money at problems….it’s actually callous, thoughtless and lazy. Which is why they’ll pay a fortune for junk as long as it has a prancing horse on it (Ferrari) or it comes in a blue box (Tiffany). Maybe it will take the next generation to make real changes since this one is pretty ossified.