The classic Psychologist laboratory animal study involves genetically identical rats living in cages divided into two groups – one control group and one with some experimental intervention. Blinded observations of some pre-defined outcome parameter are recorded and the groups compared statistically at the end of the study. By making everything about the groups exactly the same, you can reasonably conclude that any differences in the outcome parameters are caused by the intervention. In another variation, one might have a single group with a control period of observations, then a second period making the intervention – comparing the control period to the experimental period. Whatever the case, the point is to aim for uniform groups with the only difference being the intervention – control vs experimental.

The classic Psychologist laboratory animal study involves genetically identical rats living in cages divided into two groups – one control group and one with some experimental intervention. Blinded observations of some pre-defined outcome parameter are recorded and the groups compared statistically at the end of the study. By making everything about the groups exactly the same, you can reasonably conclude that any differences in the outcome parameters are caused by the intervention. In another variation, one might have a single group with a control period of observations, then a second period making the intervention – comparing the control period to the experimental period. Whatever the case, the point is to aim for uniform groups with the only difference being the intervention – control vs experimental.

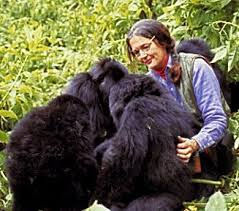

And then there are the Ethologists who do just the opposite. They often try not to interfere or make their presence known at all. So they sit in trees in the jungle and watch the animals in their natural habitat [or even become a part of it eg Dian Fossey]. Their books tend to be about one individual or a small group – more like a case study or a family study. And the tables, graphs, and statistics aren’t so prominent as they are in the works of the laboratory based scientists. They’re replaced by narrative descriptions.

And then there are the Ethologists who do just the opposite. They often try not to interfere or make their presence known at all. So they sit in trees in the jungle and watch the animals in their natural habitat [or even become a part of it eg Dian Fossey]. Their books tend to be about one individual or a small group – more like a case study or a family study. And the tables, graphs, and statistics aren’t so prominent as they are in the works of the laboratory based scientists. They’re replaced by narrative descriptions.

1. Hypothesis Testing Research versus Material-Exploration

Scientific research and reasoning continually pass through the phases of the well-known empirical-scientific cycle of thought: observation – induction – deduction – testing [observe – guess – predict – check]. The use of statistical tests![Adrianus de Groot l1914-2006] Adrianus de Groot l1914-2006]](http://1boringoldman.com/images/degroot.gif) is of course first and foremost suited for “testing”, i.e., the fourth phase. In this phase one assesses whether certain consequences [predictions], derived from one or more precisely postulated hypotheses, come to pass. It is essential that these hypotheses have been precisely formulated and that the details of the testing procedure [which should be as objective as possible] have been registered in advance. This style of research, characteristic for the [third and] fourth phase of the cycle, we call hypothesis testing research.

is of course first and foremost suited for “testing”, i.e., the fourth phase. In this phase one assesses whether certain consequences [predictions], derived from one or more precisely postulated hypotheses, come to pass. It is essential that these hypotheses have been precisely formulated and that the details of the testing procedure [which should be as objective as possible] have been registered in advance. This style of research, characteristic for the [third and] fourth phase of the cycle, we call hypothesis testing research.

This should be distinguished from a different type of research, which is common especially in [Dutch] psychology and which sometimes also uses statistical tests, namely material-exploration. Although assumptions and hypotheses, or at least expectations about the associations that may be present in the data, play a role here as well, the material has not been obtained specifically and has not been processed specifically as concerns the testing of one or more hypotheses that have been precisely postulated in advance. Instead, the attitude of the researcher is: “This is interesting material; let us see what we can find.” With this attitude one tries to trace associations [e.g., validities]; possible differences between subgroups, and the like. The general intention, i.e. the research topic, was probably determined beforehand, but applicable processing steps are in many respects subject to ad-hoc decisions. Perhaps qualitative data are judged, categorized, coded, and perhaps scaled; differences between classes are decided upon “as suitable as possible”; perhaps different scoring methods are tried along-side each other; and also the selection of the associations that are researched and tested for significance happens partly ad-hoc, depending on whether “something appears to be there”, connected to the interpretation or extension of data that have already been processed.

When we pit the two types so sharply against each other it is not difficult to see that the second type has a character completely different from the first: it does not so much serve the testing of hypotheses as it serves hypothesis-generation, perhaps theory-generation — or perhaps only the interpretation of the available material itself.

Although we can never achieve the uniformity of subjects or conditions as with the lab rats, we do use the Hypothesis Testing [lab rat] model for our Clinical Trials of medications. It makes sense given what we’re trying to find out – "Does this molecule have medicinal properties in the defined condition?" Usually, I bring up de Groot to emphasize the absolute necessity for preregistration ["It is essential that these hypotheses have been precisely formulated and that the details of the testing procedure … have been registered in advance"] – a point that cannot be emphasized too much given the ubiquity of "outcome switching" in clinical trial reports. This time, however, I’m bringing it up for a different reason. While the Clinical Trial method gives us a powerful tool for evaluating a medication’s effects, clinical medicine is a different story. Practicing physicians don’t see groups. We see one patient at a time, and our experience is more like a long series of case studies than a Randomized Clinical Trial – a string of anecdotes stretching from medical school to the present. And those adverse events mumbled at the end of Direct-to-Consumer ads are a haunting reality to be reckoned with.

An Anecdote: A young pregnant woman presented to the ER of our UK military hospital one evening with a severe URI and sore throat. She was given symptomatic medications and started on penicillin. The next day [a Sunday], she returned with a skin rash thought to be a reaction to the penicillin, and it was stopped. By Monday when she returned, the rash covered her body and she was admitted with a diagnosis of

Stevens-Johnson Syndrome. We had two Internists, an Ophthalmologist, a Dermatologist, and we were 25 miles away from Addenbrooks Hospital in Cambridge who supplied a steady stream of expert consultants throughout her hospital stay. When we were finally able to send her back to the US months later, she’d survived what amounted to massive burns; she was blind; she’d lost her child; she survived kidney failure and was off of peritoneal dialysis. I heard from her about a year later excited to say that she was beginning to regain some of her sight. The young general medicine officer who’d initially given her the penicillin [at her request] saw her every day over those months, and after his military service, he became an Ophthalmologist – an interest he developed while following her eye-care with the British consultants. After the fact, one never knows if this kind of maelstrom was from the original viral infection or the penicillin – both listed as possible causes in such cases. And I, for one, have never seen another such case. With an incidence of single digits per million people per year, many physicians have never seen this illness. I expect that those of us involved in this case

see her every time we consider antibiotics for a sore throat or see a penicillin reaction.

Over time, I’ve come to see the two poles of drug testing and approval – efficacy and safety – as separate matters. The Randomized Clinical Trial [RCT] is good enough for efficacy if conducted correctly [de Groot style]. The Statistics and calculations of Effect Sizes can offer a reasonable place to start with clinical usage. I’m less impressed that the RCT has that same valence when it comes to safety. In fact, the FDA must agree because they require Adverse Event reporting on all subjects in all phases of all trials to be included in the New Drug Approval [NDA] submissions instead of trial-wise data. And the trials are short compared to most clinical usage. But beyond that, there are so many ways to bury the magnitude of of an Adverse Effect in the system of classification or language used eg logging suicidality in as "emotional lability" in Paxil Study 329.

In the overwhelming majority of cases, penicillin doesn’t have any effect on the course of a sore throat, whether caused by the Streptococci organisms or not. If, however, it is a Strept Throat, there was a time when the result might well be Scarlet Fever, Rheumatic Fever, Acute Glomerulonephritis – conditions that had long term and often ominous consequences. That penicillin shot has virtually eliminated those once common illnesses – a medical miracle. But the reason to get a culture to be sure it’s a Strept Throat first instead of treating all Sore Throats as Strept Throats is another kind of prevention – to minimize the possibility of cases like the one described above [among other things].

Evidence-Based Medicine is built on the model of the Randomized Clinical Trial – as if its group oriented answers dictate the practice of medicine. It’s particularly popular with people in charge of planning and policy. It gives an illusion of predictability and clarity that’s often absent in real-life clinical situations. The bell shaped curves of biology get reduced to the mean, and statistics are no longer probabilities but get treated as certainties. Guidelines that were originally derived to make sure doctors didn’t miss anything have been perverted into cost-cutting restraints or even ways to push unnecessary treatments. And the principles of preventive medicine have been coopted by a natural health industry rivaling the patent medicine hawkers of yore. RCTs were developed as tools to help physicians and patients negotiate the multivariant living case histories we share. They were never meant to be twisted and turned to market anything. But beyond that, RCTs are hardly the model for medical care itself, and are of only limited use in evaluating anything but short term safety. We all know the dangers of Anecdote-Based Medicine [and they are many], but we seem to have gone blind to its strengths…

The classic Psychologist laboratory animal study involves genetically identical rats living in cages divided into two groups – one control group and one with some experimental intervention. Blinded observations of some pre-defined outcome parameter are recorded and the groups compared statistically at the end of the study. By making everything about the groups exactly the same, you can reasonably conclude that any differences in the outcome parameters are caused by the intervention. In another variation, one might have a single group with a control period of observations, then a second period making the intervention – comparing the control period to the experimental period. Whatever the case, the point is to aim for uniform groups with the only difference being the intervention – control vs experimental.

The classic Psychologist laboratory animal study involves genetically identical rats living in cages divided into two groups – one control group and one with some experimental intervention. Blinded observations of some pre-defined outcome parameter are recorded and the groups compared statistically at the end of the study. By making everything about the groups exactly the same, you can reasonably conclude that any differences in the outcome parameters are caused by the intervention. In another variation, one might have a single group with a control period of observations, then a second period making the intervention – comparing the control period to the experimental period. Whatever the case, the point is to aim for uniform groups with the only difference being the intervention – control vs experimental. And then there are the Ethologists who do just the opposite. They often try not to interfere or make their presence known at all. So they sit in trees in the jungle and watch the animals in their natural habitat [or even become a part of it eg Dian Fossey]. Their books tend to be about one individual or a small group – more like a case study or a family study. And the tables, graphs, and statistics aren’t so prominent as they are in the works of the laboratory based scientists. They’re replaced by narrative descriptions.

And then there are the Ethologists who do just the opposite. They often try not to interfere or make their presence known at all. So they sit in trees in the jungle and watch the animals in their natural habitat [or even become a part of it eg Dian Fossey]. Their books tend to be about one individual or a small group – more like a case study or a family study. And the tables, graphs, and statistics aren’t so prominent as they are in the works of the laboratory based scientists. They’re replaced by narrative descriptions.is of course first and foremost suited for “testing”, i.e., the fourth phase. In this phase one assesses whether certain consequences [predictions], derived from one or more precisely postulated hypotheses, come to pass. It is essential that these hypotheses have been precisely formulated and that the details of the testing procedure [which should be as objective as possible] have been registered in advance. This style of research, characteristic for the [third and] fourth phase of the cycle, we call hypothesis testing research.

I have a different opinion on it:

http://real-psychiatry.blogspot.com/2016/02/anecdotes-are-not-evidence-and-other.html

At some point the anecdotal becomes the statistical. Clinical practice allows physicians to accumulate tens of thousands of clinical features that they base their decisions on. You hit the nail on the head on the A-B comparison in a clinical trial that assumes fairly uniform samples discriminated only on the variable of choice. In fact both the treatment group and the controls are heterogeneous groups and in the case of psychiatry – the heterogeneity is compounded by polygenes and epigenetics. The qualifying trials for some FDA trials are flawed out of the box for what I would consider obvious reasons. The best example I can think of is using a stimulant to treat binge eating when we know that stimulants did not work for obesity and that a substantial number of those patients continued to take stimulants despite no weight loss:

http://real-psychiatry.blogspot.com/2015/02/did-fda-forget-about-americas-first.html

It is around this that there is possibly the greatest disagreement:

“It is when asking questions about therapy that we should try to avoid the non-experimental approaches, since these routinely lead to false positive conclusions about efficacy. Because the randomised trial, and especially the systematic review of several randomised trials, is so much more likely to inform us and so much less likely to mislead us, it has become the “gold standard” for judging whether a treatment does more good than harm.”

https://www.cebma.org/wp-content/uploads/Sackett-Evidence-Based-Medicine.pdf

As someone who’s been in the “system” on and off for half of my life, I have gone from completely accepting the standard biopsychiatric narrative to questioning to rejecting it completely.

When I saw a shrink at 15 for depression and anxiety and OCD, we talked for 15 minutes, after which he prescribed Prozac (right after he said I was probably abused as a child: why he came to that conclusion I have no idea).

That was the beginning of my long journey.

Several types of antidepressants and antipsychotics later, and with two hospitalizations in my history, I am now 30 and have quit the meds for good. I have also been reading a lot about the facts involved in psychological disturbance and gradually every single thing I used to believe has been disproven to me. The nonsense brain scans, the “missing heritability” (which will likely remain “missing” forever), etc….

Perhaps I have gone too far in rejecting the medical model. I don’t know.

I discovered your site yesterday and find what you have written very interesting so far. Keep up the good work.