Our tour leader, Tony [Antonio], was quite a character. He’s guided photographic Safaris for 29 years – which is as long as they’ve existed. In 1977, Kenya [and later Tanzania] outlawed all Big Game hunting, and trips such as ours is what took their place. He grew up in Mozombique. At 12, he was in a boarding school studying to be a priest, when he was lured away with promise of studying abroad. It was a trick, and he ended up being a child soldier in Tanganyika resistance army. Being too young to hold a rifle, he was moved to a school where he was part of a student revolt over food. From the strrets, he was taken in by a Portuguese family and finished high school in Kenya where he had sought political asylum. Working as a tour guide, he met a German family from Brazil who sent him to college [Nairobi for a year and a half, the rest in San Diego]. The poverty of being a teacher didn’t suit him, so he became a Safari Guide. He was reunited with his biological family in his forties, having been given up for dead for thirty years. And that’s just one of his stories.

When we finally got to Masai Mara and left immediately on an afternoon game drive, he said, "It’s not like the Zoo where the animals are in cages. We’re the ones in the cages, and they look at us." And that was exactly right. The eighteen of us had travelled in three Toyota Vans. They had six seats in the back and a top that "popped up" so you could stand. Some tour groups had Land Cruisers, and we were envious. Later in the trip, we were in Land Cruisers. It was no different. The only thing that would smooth out the African roads was an airplane, and as we would later learn, African airplanes had their own down-side.

When we finally got to Masai Mara and left immediately on an afternoon game drive, he said, "It’s not like the Zoo where the animals are in cages. We’re the ones in the cages, and they look at us." And that was exactly right. The eighteen of us had travelled in three Toyota Vans. They had six seats in the back and a top that "popped up" so you could stand. Some tour groups had Land Cruisers, and we were envious. Later in the trip, we were in Land Cruisers. It was no different. The only thing that would smooth out the African roads was an airplane, and as we would later learn, African airplanes had their own down-side.

Mara means "dotted." Unlike the bare flat Serengeti to the south, Masai Mara is low rolling hills dotted with bushes and Acacia trees. So in this picture looking from Massai Mara into the Serengeti, the dots in the foreground are one of the countless Wildebeast herds. The dots in the middle two sections are mostly bushes. And the distant landscape is the "bushless" Serengeti. The horizontal tree lines are small rivers.

I hate it when someone has seen a great movie and tries to tell you about it. They use increasingly superlative terms trying to convey the wonder they’ve seen. All is lost on the listener, who, of course, hasn’t seen the movie. So I find myself in the same spot. I’ve already posted a collage of photos from that first outing below. While we we on the drive, we were clicking photos so fast that I don’t think we thought very much, but when we got back, I found myself uncharacteristically moved, with tears flowing down my face. Forgotten were the slums of Nairobi, or the roads, or the day and a half flight it took to get to Africa. I just couldn’t believe that I’d seen what I’d seen. That’s all [Supply your own superlatives as needed].

The Herds

Photographing a herd isn’t really possible, at least the herds on the African Plain. They spread out over a huge area. The biggest herds are Wildebeests and Zebras, often mixed together. They are "the Migration." Zebras eat the top of the grass, Wildebeests eat the lower clumps that are left. Zebras have keen hearing and smell, but see poorly. Wildebeests hear and smell poorly, but have great vision. So these complementary species move together in the endless cycle of the African Migration, joined haphazardly by the other grazers. Elephants often graze alone, but move about together in small herds. There are many fewer elephants, but the comsume the majority of the grass. The Buffalo also congregate in great herds, but don’t join the predictable Migration with the Zebras and Wildebeests. The bottom collage is an attempt to show the endless single file lines that stretch as far as the eye can see as these herds move from place to place.

Antelopes and Gazelles

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

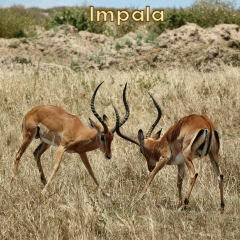

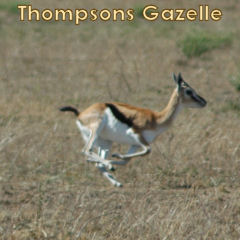

There are Antelopes and Gazelles everywhere in groups rather than herds. The large, shy Elands and the smaller Impalas move in large harems of females with a single male. The Topis and Hartebeests have smaller family groups. The tiny Gazelles literally pepper the Plains [The "Tommies" above are fleeing my wife in a Hot Air Baloon]. The two types of Gazelles are differentiated by the tail color and the back leg markings.

Other Grazers

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

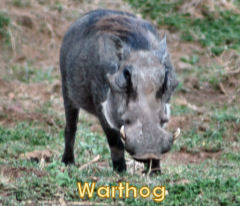

Ostriches are solitary grazers, standing alone on the grassy plains. The story is that the female guards their 12 omlet eggs by day and the black male stands guard at night – for camouflage [Obviously this pair hasn’t been told this story]. The elegant Giraffes speak for themselves. I don’t know what I thought Hippos eat. They’re actually grazers on the plains as well – they just feed at night. They’re very heat and light sensitive, so they spend their days in and by the water, grazing at night. Another thing I didn’t know, they’re the most dangerous of the lot to humans. When they head back for water in the pre-dawn light, they kill anything that gets in their way. Lesson: If you’re foolish enough to camp on the African Plain, stay away from the river’s bank. Warthogs are a surprisingly frisky lot [their short necks interfere with rooting, so they kneel].

Predators and Scavengers

The African Plain is essentially self-cleaning. Hyenas are both predators and scavengers. If one sees a group of Antelopes or Gazelles all looking in the same direction, the Hyenas are bound to be somewhere at the other end of their gaze – hunting for their children. If you see Vultures on a piece of carrion, you can bet that a Hyena or two will show up sooner or later to run off with their spoils.

The African Rivers are self-cleaning too, but the cleaner-upper Crocodiles make the Hyenas look tame. If the Crocs clean up the water, what’s that pile of carcasses below on the right? I spared you a close up for aesthetic reasons. "The Migration" has to cross two main rivers in its endless circling. At the Mara River, they cross when it’s swollen during the Rainy Season, and many Wildebeests perish in the process [the down-side of following the leader]. So many, that even the voracious Crocodiles and Vultures can’t take care of the load. So there are always piles of them for the other birds [and time] to pick at.

I started off saying that people trying to tell about something they’ve seen get carried away, and I can see that I’ve done the same thing. Were I reading this, I’d wonder if the author was trying to photograph every animal in Africa. I can assure you that I’ve just hit a few of the high points during our first 2½ days. But there’s more to an African trip than just cataloguing the species like at the Zoo. There’s a lot about seeing how this complex ecosystem works in action – like returning to a place to where the Vultures waited for the Lion’s exit to find the Vultures hard at work only to be thwarted by a pack of Hyenas. I’ll end with another such story.

Rhinos have been poached almost to extinction in Masa Mara for their horns – thought to be an aphrodisiac in the East [Tony says that Viagra may save the Rhino]. So, finding a Rhino is a real treat. On our last game drive in Masai Mara, we were watching two lions [in a pride of seven] playing by a small river when the radio started to crackle [in Kiswahili], and our driver began to race across the plain. When we stopped, we joined another van straining our eyes into the bush to see a Rhino [maybe] off in an inaccessible area. Slowly it moved down the hill as other vans began to show up – ultimately twenty plus [all there were in all of Massai Mara]. The Rhino stopped under a sausage tree for a snack [and the last chance of a photograph in the fading light].

Rhinos have been poached almost to extinction in Masa Mara for their horns – thought to be an aphrodisiac in the East [Tony says that Viagra may save the Rhino]. So, finding a Rhino is a real treat. On our last game drive in Masai Mara, we were watching two lions [in a pride of seven] playing by a small river when the radio started to crackle [in Kiswahili], and our driver began to race across the plain. When we stopped, we joined another van straining our eyes into the bush to see a Rhino [maybe] off in an inaccessible area. Slowly it moved down the hill as other vans began to show up – ultimately twenty plus [all there were in all of Massai Mara]. The Rhino stopped under a sausage tree for a snack [and the last chance of a photograph in the fading light].

After a time, the Rhino lumbered down the hill towards the river. From the right, a Lion appeared, then another, until all seven from the pride we’d been watching were lined up stalking the Rhino. So the scene changed. There was now a circle of Lions around the Rhino who was turning from one to the other in quick succession, covering its back. Finally, one of the Lions began to advance. The Rhino took off towards it like a souped-up drag racer, head down. The Lion retreated in a flash. After this confrontation, the circle got much wider and the rest of the pride sat down in the grass. The Rhino ambled off into the trees along the river, and the Lions went back to their play. Tony told us later that it would take more than seven to kill a Rhino and they’d have to be mighty hungry because they’d lose several sisters in the process. He said the Rhino was just circling waiting for the leader to show herself to put the fear of God into her.

After a time, the Rhino lumbered down the hill towards the river. From the right, a Lion appeared, then another, until all seven from the pride we’d been watching were lined up stalking the Rhino. So the scene changed. There was now a circle of Lions around the Rhino who was turning from one to the other in quick succession, covering its back. Finally, one of the Lions began to advance. The Rhino took off towards it like a souped-up drag racer, head down. The Lion retreated in a flash. After this confrontation, the circle got much wider and the rest of the pride sat down in the grass. The Rhino ambled off into the trees along the river, and the Lions went back to their play. Tony told us later that it would take more than seven to kill a Rhino and they’d have to be mighty hungry because they’d lose several sisters in the process. He said the Rhino was just circling waiting for the leader to show herself to put the fear of God into her.

I wonder how many thousands of visitors have tried [and failed] to describe how it is on the African Plain – how the climate, the seasonal weather, the time of day, the terrain, the plants, and the animals play out their endless cycle of life and death in this wonderous place. In all of it, there’s a simple wholeness to the puzzle that probably defies words, living more in the spiritual than the scientific realm. It’s what gives Africa its unique character, the mystery that can’t be written or photographed.

I wonder how many thousands of visitors have tried [and failed] to describe how it is on the African Plain – how the climate, the seasonal weather, the time of day, the terrain, the plants, and the animals play out their endless cycle of life and death in this wonderous place. In all of it, there’s a simple wholeness to the puzzle that probably defies words, living more in the spiritual than the scientific realm. It’s what gives Africa its unique character, the mystery that can’t be written or photographed.

And the Maasai in their circular villages with their precious cattle fit into the story as just a part of it all. Even though we know better, we humans tend to see ourselves at the center of things. On the African Plain, they know the truth.

They say a picture is worth a thousand words. Your pictures of your masai mara safari are definately worth a thousand or more. It’s always hard to describe to someone who has never been to Africa what to expect.