U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statementby Albert L. Siu, MD, MSPH, on behalf of the U.S. Preventive Services Task ForceAnnals of Internal Medicine. Published online 9 February 2016

Description: Update of the 2009 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force [USPSTF] recommendation on screening for major depressive disorder [MDD] in children and adolescents.Methods: The USPSTF reviewed the evidence on the benefits and harms of screening; the accuracy of primary care–feasible screening tests; and the benefits and harms of treatment with psychotherapy, medications, and collaborative care models in patients aged 7 to 18 years.Population: This recommendation applies to children and adolescents aged 18 years or younger who do not have a diagnosis of MDD.Recommendation: The USPSTF recommends screening for MDD in adolescents aged 12 to 18 years. Screening should be implemented with adequate systems in place to ensure accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, and appropriate follow-up. [B recommendation] The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for MDD in children aged 11 years or younger.

A Systematic Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Forceby Valerie Forman-Hoffman, PhD, MPH; Emily McClure, MSPH; Joni McKeeman, PhD; Charles T. Wood, MD; Jennifer Cook Middleton, PhD; Asheley C. Skinner, PhD; Eliana M. Perrin, MD, MPH; and Meera Viswanathan, PhDAnnals of Internal Medicine. Published online 9 February 2016

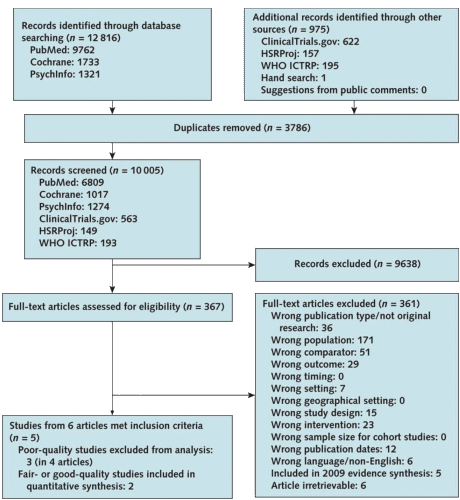

Background: Major depressive disorder [MDD] is common among children and adolescents and is associated with functional impairment and suicide.Purpose: To update the 2009 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force [USPSTF] systematic review on screening for and treatment of MDD in children and adolescents in primary care settings.Data Sources: Several electronic searches [May 2007 to February 2015] and searches of reference lists of published literature.Study Selection: Trials and recent systematic reviews of treatment, test–retest studies of screening, and trials and large cohort studies for harms.Data Extraction: Data were abstracted by 1 investigator and checked by another; 2 investigators independently assessed study quality.Data Synthesis: Limited evidence from 5 studies showed that such tools as the Beck Depression Inventory and Patient Health Questionnaire for Adolescents had reasonable accuracy for identifying MDD among adolescents in primary care settings. Six trials evaluated treatment. Several individual fair- and good-quality studies of fluoxetine, combined fluoxetine and cognitive behavioral therapy, escitalopram, and collaborative care demonstrated benefits of treatment among adolescents, with no associated harms.Limitation: The review included only English-language studies, narrow inclusion criteria focused only on MDD, high thresholds for quality, potential publication bias, limited data on harms, and sparse evidence on long-term outcomes of screening and treatment among children younger than 12 years.Conclusion: No evidence was found of a direct link between screening children and adolescents for MDD in primary care or similar settings and depression or other health-related outcomes. Evidence showed that some screening tools are accurate and some treatments are beneficial among adolescents [but not younger children], with no evidence of associated harms.

I came to psychiatry drawn by the psychological struggles apparent in so many of the medical patients I’d seen along the way. I just didn’t get it. And learning to view them in the context of the person’s whole biography was, in itself, worth the price of admission for me. When the DSM-III with its expanded focus on distinct disorders came along, I was neither interested nor able to go back, so I went away. I understood and even agreed with many of the criticisms of what had been before, but I couldn’t live with the baby in the bathwater problem. I see non-melancholic depression as a signal that something’s wrong that needs attending rather than just a symptom to be treated. And that’s particularly true in adolescence and young adulthood. I really don’t think there’s a unitary disease, Major Depressive Disorder [MDD], even in adulthood, but I double-dog-really don’t think it exists in children and adolescents – certainly not in the way these articles imply. Five years volunteering in a Child and Adolescent clinic after retirement only reinforced these views.

So as important as I think it is to attend to depression in adolescents, this recommendation and the accompanying review just seem way off the mark. And to present this slide as an updated "Systematic Review" is ludicrous:

[truncated to fit]

Almost everything well-intended these days is ill-advised. I think these proposals ought to be like the TV drug ads, in which the company lists the ten most common side effects. Consider:

1. Patients who own a gun or who want to own a gun will not report depressive symptoms and will not be treated, especially in states like New York.

2. Transient adjustment disorders and grief will be medicalized and overtreated.

3. Disorders of sleep (such as OSA) will be mistreated or mislabeled as psychiatric disorders.

4. This same problem applies to any of the nonspecific somatic symptoms of depression.

5. Most importantly, we have imposed another distracting obligation on the physician trying to do their job in the field they know best.

The only thing worse than this is screening in the schools. Because after all the schools have a financial incentive to identify “special needs” children because that leads to more funding. This had quite a bit to do with the explosion of ADHD diagnoses. In fact ADHD is a perfect reason why anyone with a financial incentive should not be involved in screening paradigms where more positives mean more money.

Besides, if you’re not at least a little miserable and pissed off when you’re 14, you’re not paying attention.

We shape our tools and afterwards our tools shape us (McLuhan). This instance of depression screening illustrates the point perfectly. Max Hamilton, who introduced the first scale for depression in 1960, always insisted that his scale is a measure of severity for someone already given the diagnosis rather than a diagnostic scale in its own right. There has been a lot of slippage since then.

So-called masked depression was often discussed back in the 1960s. My teachers liked to say that in such cases the mask is on the doctor rather than on the patient.

And don’t underestimate the lure of money. We now have people hawking the idea of depression scale apps for smart phones.

The Chicago Tribune has been running a very good series on dangerous drug interactions. The latest installment told the story of a woman who almost died — and has permanent neurological damage — from Stevens-Johnson Syndrome. Which was brought on by a combination of lamotrigine (Lamictal) and sodium valproate (Depakote).

She got this wondrous combination after discussing her domestic troubles, anxiety and distress with a doctor at the urgent-care clinic where she worked. After a fifteen-minute chat over coffee, he thought there was a good chance she had bipolar disorder. And prescribed two drugs known for a risk of SJS (Lamictal actually carries a Black Box Warning for it.)

So if anyone asks you why over-screening and “false positives” might be a problem for depressive disorders, tell them about Becky Conway, who is just grateful to be alive:

http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/watchdog/druginteractions/ct-drug-interactions-skin-reaction-met-20160209-story.html