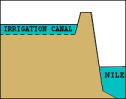

This picture from our Egypt trip of a faluka [the boat] on the Nile is typical of the Nile in upper Egypt [the south]. Planted, level fields stretch for a variable distance broken by parallel and perpendicular lines [which are irrigation ditches]. Beyond the fields is always desert, in this case, the beginnings of the low mountains that hold the Valley of the Kings and other antiquities. Egypt, at least inhabited Egypt, is at most a few miles wide from Aswan in the south up to Cairo, where the Nile fans out.

So, how does the water get from the Nile to the ditches? It’s not very far [depending on the season].

So, how does the water get from the Nile to the ditches? It’s not very far [depending on the season].  There are three ancient methods, all of which remain in widespread use. The simplest is the shaduf, a counter-weighted lever bucket apparatus. Dip the bucket in, lift it out, spin it to the ditch, then dump it. Repeat for centuries. There are smaller versions that can be operated with one hand [by a mother holding a child].

There are three ancient methods, all of which remain in widespread use. The simplest is the shaduf, a counter-weighted lever bucket apparatus. Dip the bucket in, lift it out, spin it to the ditch, then dump it. Repeat for centuries. There are smaller versions that can be operated with one hand [by a mother holding a child]. ![]()

Another method is the Archimedes Screw, which is operated by a hand crank. It’s more labor intensive, but moves more water. But if you’ve got a large field, you need a water buffalo to turn your Saqiya with its wooden gears and water wheel.

Another method is the Archimedes Screw, which is operated by a hand crank. It’s more labor intensive, but moves more water. But if you’ve got a large field, you need a water buffalo to turn your Saqiya with its wooden gears and water wheel.  Floating down the Nile, all of these primitive methods of moving water from the Nile into the Irrigation Ditches were in use. In fact, if there were other methods, like pumps, I didn’t see them anywhere. What our guide said was that there were some places where more modern pumps were in use because there was no other choice, but that the old methods were always used as the first line. It wasn’t because they didn’t have electric pumps or electricity. It was because they didn’t want to put people out of work. At first, I was suspicious of this answer, thinking it might be a way of denying the poverty in much of Egypt. But as we continued up the Nile, I became convinced. It was only one of several examples of this concept that seemed foreign to our American way of thinking.

Floating down the Nile, all of these primitive methods of moving water from the Nile into the Irrigation Ditches were in use. In fact, if there were other methods, like pumps, I didn’t see them anywhere. What our guide said was that there were some places where more modern pumps were in use because there was no other choice, but that the old methods were always used as the first line. It wasn’t because they didn’t have electric pumps or electricity. It was because they didn’t want to put people out of work. At first, I was suspicious of this answer, thinking it might be a way of denying the poverty in much of Egypt. But as we continued up the Nile, I became convinced. It was only one of several examples of this concept that seemed foreign to our American way of thinking.

We sailed about a third of the Nile on a Deisel powered Nile cruiser, one of many taking tourists from site to site. We only saw a few barges pushed by deisel powered tugs. But other than that, the boats on the river were either falukas like the one above, or small row boats [used by most of the fishermen]. The idea of avoiding automatic technology in order to allow people to have jobs, or to use wind and human powered boats so as to not rely of fossil fuels took some getting used to. As we cruised along the Nile, I only saw two "powerboats" of the kind that roar around our lakes during the whole trip. There were falukas without sails that had outboard motors, but they looked to be in the fifteen to twenty horsepower range [and very old].

On land, there were plenty of two-wheeled donkey carts being used to transport goods around the towns, or just being ridden. The horse-drawn taxis were popular with tourists, but were also in wide use by the locals. There were lots of handcrafts – ornamental rugs, alabaster jugs, mosaics, etc. But there were also a lot of non-touristy things being made by hand – like adobe bricks, hand formed and hand fired. It never occurred to me that all the primitive seeming methods were being maintained to keep people employed, but that actually seemed to be the case – at least in Upper Egypt.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.