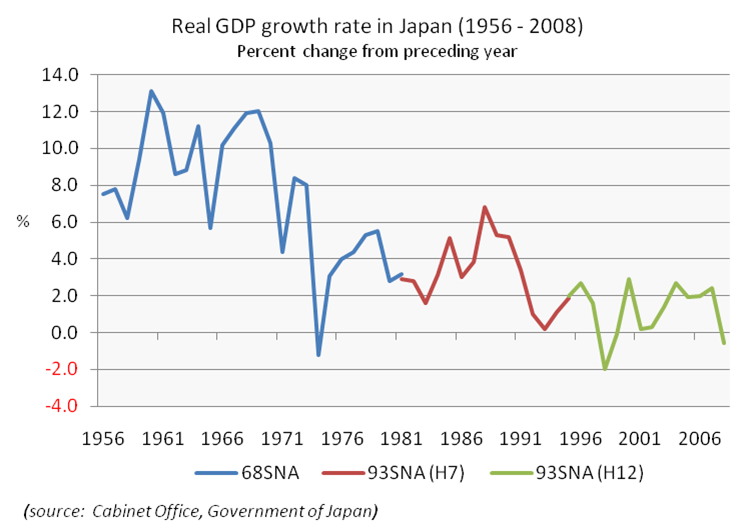

Despite a chorus of voices claiming otherwise, we aren’t Greece. We are, however, looking more and more like Japan. For the past few months, much commentary on the economy — some of it posing as reporting — has had one central theme: policy makers are doing too much. Governments need to stop spending, we’re told. Greece is held up as a cautionary tale, and every uptick in the interest rate on U.S. government bonds is treated as an indication that markets are turning on America over its deficits. Meanwhile, there are continual warnings that inflation is just around the corner, and that the Fed needs to pull back from its efforts to support the economy and get started on its “exit strategy,” tightening credit by selling off assets and raising interest rates…

But the truth is that policy makers aren’t doing too much; they’re doing too little. Recent data don’t suggest that America is heading for a Greece-style collapse of investor confidence. Instead, they suggest that we may be heading for a Japan-style lost decade, trapped in a prolonged era of high unemployment and slow growth…

As of Thursday, the 10-year rate was below 3.3 percent. I wish I could say that falling interest rates reflect a surge of optimism about U.S. federal finances. What they actually reflect, however, is a surge of pessimism about the prospects for economic recovery, pessimism that has sent investors fleeing out of anything that looks risky — hence, the plunge in the stock market — into the perceived safety of U.S. government debt.What’s behind this new pessimism? It partly reflects the troubles in Europe, which have less to do with government debt than you’ve heard; the real problem is that by creating the euro, Europe’s leaders imposed a single currency on economies that weren’t ready for such a move. But there are also warning signs at home, most recently Wednesday’s report on consumer prices, which showed a key measure of inflation falling below 1 percent, bringing it to a 44-year low.

This isn’t really surprising: you expect inflation to fall in the face of mass unemployment and excess capacity. But it is nonetheless really bad news. Low inflation, or worse yet deflation, tends to perpetuate an economic slump, because it encourages people to hoard cash rather than spend, which keeps the economy depressed, which leads to more deflation. That vicious circle isn’t hypothetical: just ask the Japanese, who entered a deflationary trap in the 1990s and, despite occasional episodes of growth, still can’t get out. And it could happen here…

In short, fear of imaginary threats has prevented any effective response to the real danger facing our economy. Will the worst happen? Not necessarily. Maybe the economic measures already taken will end up doing the trick, jump-starting a self-sustaining recovery. Certainly, that’s what we’re all hoping. But hope is not a plan.

I finally decided that Krugman was like a young Dental Hygienist. You know the kind I mean. They talk to you like the only thing that really matters in your day is tooth care. So you leave feeling guilty and do the best you can, given that you have a non-Dental life that occupies a lot of the time they’d like for you to spend on your teeth. They’re right, but impractical. I expect Krugman is right, but he wants more than is possible. If Obama tried to do what he says right now, we’d have all Republicans in Congress soon and another Bush in 2012. So, there are other things besides Keynesian Economics to consider. And frankly, after this last decade, there are worse things than having Americans focused on getting the National Debt down

I finally decided that Krugman was like a young Dental Hygienist. You know the kind I mean. They talk to you like the only thing that really matters in your day is tooth care. So you leave feeling guilty and do the best you can, given that you have a non-Dental life that occupies a lot of the time they’d like for you to spend on your teeth. They’re right, but impractical. I expect Krugman is right, but he wants more than is possible. If Obama tried to do what he says right now, we’d have all Republicans in Congress soon and another Bush in 2012. So, there are other things besides Keynesian Economics to consider. And frankly, after this last decade, there are worse things than having Americans focused on getting the National Debt down

We need Krugman just like we need Dental Hygienists. He’s just doing his job, and he’s probably right that we’re playing it too close to the wire to hope for a robust, or a guaranteed recovery. Maybe we’ll have a lost decade. In fact, maybe we earned a lost decade fair and square. Maybe it’ll take a lost decade to get things right, but I don’t think that hinges just on Keynesian Economics. In the last century, we had a couple of lost decades – the Great Depression and a great war [WWII]. They put the brakes on run-away Capitalism and wealth accumulation. We changed our ways because we had to, not because we wanted to. Then, fifty years later, we started changing back, and hit the wall again. Back in the days of John Maynard Keynes, we had the option of unlimited growth. We don’t have that anymore. If anything, we need to think about shrinking. It’s time for a major paradigm shift – in our values, and maybe in our economics.

Perhaps Japan needed their lost decade. Perhaps we do too. I think the way things go depends more on the awakenings in the private sector than Krugman realizes. We need to worry about population control, global warming, downsizing our population of the incredibly wealthy, and finding our proper place in the world. Until those things happen, we don’t deserve a robust recovery. Last night’s Financial Regulatory Bill is a start. So I think hope is a plan. Hope for what is the issue. We can’t just spend our days flossing and brushing…

Perhaps Japan needed their lost decade. Perhaps we do too. I think the way things go depends more on the awakenings in the private sector than Krugman realizes. We need to worry about population control, global warming, downsizing our population of the incredibly wealthy, and finding our proper place in the world. Until those things happen, we don’t deserve a robust recovery. Last night’s Financial Regulatory Bill is a start. So I think hope is a plan. Hope for what is the issue. We can’t just spend our days flossing and brushing…

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.