My apologies for going on and on about the DSM-III. I guess waiting thirty years, you build up a lot of feelings. Robert Spitzer came along at a time when he could’ve solved a lot of problems. The diagnostic criteria needed to be revised. Psychoanalytic theory had no place as an organizing principle. And he was correct that the nosology needed to be non-ideological. There was a real question of third party payments that needed to be addressed. Biological psychiatrists were beginning to make inroads into clarifying a number of syndromes and they needed to be isolated. Organized psychiatry was partitioned and we needed something to bring us together with mainstream medicine and each other. It was not the time for him to ally himself with one idiosyncratic way of thinking about things, while hiding behind a cloak of neutrality and objectivity. But that’s what he did. Robert Spitzer missed the moment – enabling an era none of us will look back on with any pride.

Spitzer had another shot at things eight years later with the DSM-III-R, but he mostly moved the pieces around on the board without making sustantive changes. There was still one kind of depression. Melanchholia became a Type add-on rather that a fifth-digit add-on. Here for comparison are the DSM-III and DSM-III-R criteria for Major Depression:

| DSM-III: Diagnostic criteria for a major depressive episode

|

|

A. Dysphoric mood or loss of interest or pleasure in all or almost all usual activities and pastimes. The dysphoric mood is characterized by symptoms such as the following: depressed, sad, blue, hopeless, low, down in the dumps, irritable. The mood disturbance must be prominent and relatively persistent, but not necessarily the most dominant symptom, and does not include momentary shifts from one dysphoric mood to another dysphoric mood, e.g. anxiety to depression to anger, such are seen in states of acute psychotic turmoil [For children under six, dysphoric mood may have to be inferred from a persistently sad expression.]

|

|

B.At least four of the following symptoms have each been present nearly every day for a period of at least two weeks [in children under six, at least three of the first four].:

[1] poor appetite or significant weight loss [when not dieting] or increased appetite or significant weight gain [in children under six, consider failure tomake expected weight gains]

[2] insomnia or hypersomnia

[3] psychomotor agitation or retardation [not merely subjective feelings of restlessness or being slowed down][in children under six, hypoactivity]

[4] loss of interest or pleasure in usual activities, or decrease in sexual drive not limited to a period when delusional or hallucinating [in children under six, signs of apathy]

[5] loss of energy; fatigue

[6] feelings of worthlessness, self reproach, or excessive or inappropriate guilt [either may be delusional]

[7] complaints or evidence of diminished ability to think or concentrate, such as slowed thinking, or indecissiveness not associated with marked loosening of association or incoherence

[8] recurrent thoughts of death, suicide ideation, wishes to be dead, or suicide attempt

|

|

C. Neither of the following dominate the clinical picture when an affective syndrome [i.e., criteria A and B above] is not present, that is, before it developed or after it has remitted:

[1] preoccupation with a mood-incongruent delusion or hallucination [see definition below]

[2] bizarre behavior

|

|

D. Not superimposed on either Schizophrenia, Schizophreniform Disorder, or a Paranoid Disorder.

|

|

E. Not due to any Organic Mental Disorder or Uncomplicated Bereavement.

|

|

Fifth-digit code numbers and criteria for subclassification of major depressive episode

6- In Remission…

4- With Psychotic Features…

Mood-congruent Psychotic Features:…

Mood-incongruent Psychotic Features:…

3- With Melancholia

A. Loss of pleasure in all or almost all activities

B. Lack of reactivity to usually pleasurable stimuli [doesn’t feel much better, even temporarily, when something good happens].

C. At least three of the following: [a] distinct quality of depressed mood, i.e. the depressed mood is perceived as distinctly different from the kind of feeling experience following the death of a loved one

[b] the depression is regularly worse in the morning

[c] early morning awakening [at least two hours before usual time of awakening]

[d] marked psychomotor retardation or agitation

[e] significant anorexia or weight loss

[f] excessive or inappropriate guilt

2- Without Melancholia

0- Unspecified.

|

| DSM-III-R: Diagnostic criteria for a Major Depressive Episode

|

|

A. At least five of the following symptoms have been present during the same two-week period and represent a change from previous functioning; at least one of the symptoms is either [1] depressed mood, or [2] loss of interest or pleasure [Do not include symptoms that are clearly due to a physical condition, mood-incongruent delusions or hallucinations, incoherence, or marked loosening of associations.]:

[1] depressed mood [or can be irritable mood in children and adolescents] most of the day, nearly every day, as indicated by a subjective account or observed by others.

[2] markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all,activities most of the day, nearly every day [as indicated by either a subjective account or observations by others of apathy most of the time]

[3] significant weight loss or weight gain when not dieting [e.g., more than 5% of body weight in a month], or decrease or increase in appetite every day [in children, consider failure to make expected weight gains]

[4] insomnia or hypersomnia nearly every day

[5] psychomotor agitation or retardation nearly every day [observable by others, not merely subjective feelings of restlessness or being slowed down]

[6] fatigue and loss of energy nearly every day

[7] feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt [which may be delusional] nearly every day [not merely self reproach or guilt about being sick]

[8] diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness, nearly every day [either by subjective account or observed by others]

[9] recurrent thoughts of death [not just fear of dying], recurrent suicidal ideation without a specific plan, or a suicide attempt or a specific plan for committing suicide

|

|

B.

[1] It cannot be established that an organic factor initiated and maintained the disturbance

[2] The disturbance is not a normal reaction to the death of a loved one [Uncomplicated Bereavement]

Note: Morbid preoccupation with worthiness, suicidal ideation, marked functional impairment or psychomotor retardation, or prolonged duration suggest bereavement complicated by Major Depression.

|

|

C. At no time during the disturbance have there been any delusions or hallucinations for as long as two weeks in the absence of prominent mood symptoms [i.e., before the mood symptoms developed or after they remitted].

|

|

D. Not superimposed on either Schizophrenia, Schizophreniform Disorder, Delusional Disorder, or Psychotic Disorder NOS.

|

|

Major Depressive Episode codes: fifth-digit code numbers and criteria for severity of current state of Bipolar Disorder, Depressed, or Major Depression:

1- Mild:…

2- Moderate:…

3- Severe, without Psychotic Features:…

4- With Psychotic Features…

Mood-congruent Psychotic Features:…

Mood-incongruent Psychotic Features:…

5- In Partial Remission…

6- In Remission…

0- Unspecified.

|

|

Specify chronic if current episode has lasted two consequetive years without a period of two months or longer during which there was no significant depressive symptoms. Specify if current episode is Melancholic Type. |

| DSM-III-R: Diagnostic criteria for Melancholic Type

|

|

The presence of at least five of the following:

[1] Loss of pleasure in all or almost all activities

[2] Lack of reactivity to usually pleasurable stimuli [doesn’t feel much better, even temporarily, when something good happens].

[3] the depression is regularly worse in the morning

[4] early morning awakening [at least two hours before usual time of awakening]

[5] psychomotor retardation or agitation [not merely subjective complaints]

[6] significant anorexia or weight loss [e.g., more than 5% of body weight in a month]

[7] no significant personality disturbance before the first Major Depressive Episode

[8] one or more previous Major Depressive Episodes followed by complete, or nearly complete, recovery

[9] previous good response to specific and adequate somatic antidepressant therapy, e.g., tricyclics, ECT, MAOI, lithium

|

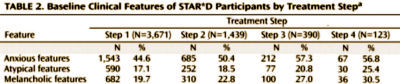

Here’s the kind of thing Spitzer’s unitary Major Depression category did. In STAR*D, they told us about the types of depression, but didn’t tell us the response rates for the types:

It’s something we’d like to know. That happened in study after study. They had the data and could’ve easily answered a question. Had Melancholia been a separate diagnostic category, we’d know if they were the patients likely to respond to somatic therapies [I suspect that the Melancholic patients improved their overall response rates][They must’ve agreed since they even added response to treatment to the diagnostic criteria].

Likewise, notice that in DSM-III -with Melancholia 3. C. [a] distinct quality of depressed mood, i.e. the depressed mood is perceived as distinctly different from the kind of feeling experience following the death of a loved one, the only one of those "music" things, disappears in DSM-III-R.

In the last few posts, I’ve criticized Spitzer’s DSM-IIIs and Spitzer from multiple directions, and without saying it directly, accused him of deceit – and I think he was deceitful in hiding his alliance to the "invisible college" in St. Louis. I think he was deceitful in his response to Dr. Carroll’s plea to reconsider a unitary depression category. I think he was deceitful to the APA and psychiatrists when he claimed that the DSM-III was atheoretical. In fact I haven’t been at all kind: deceitful, emotionally myopic, contrarian, making a coups d’état. Those are ad hominem comments that I should probably keep to myself, but I decided not to. They’re just too obvious to omit.

But there’s one thing that I’ve been thinking along the way that I haven’t said – my biggest criticism of all. I don’t think Dr. Spitzer had any belief that psychiatrists help people. His quirky time as an adolescent in the Orgone Box of the disturbed Wilhelm Reich didn’t help him. His own analysis and his work with analytic patients apparently were equally ineffective. Thereafter, he was in a Biometric Department where he worked on research projects or diagnostic criteria. Nowhere in that do I hear that he was a clinician who had the opportunity to actually help patients. He took us through two profession-changing revisions of our diagnostic criteria, the criteria we use to figure out how to help people with mental illnesses, and I find nothing in his story, his career, or the classifications he gave us that says he knew what the diagnostic criteria were actually supposed to accomplish. It was like he was classifying butterflies, a collector. And his lumping of depressed people, the most common category of people we see, into either Bipolar Illness or Major Depression is the best example of that. There’s nothing in the criteria that helps clinicians know how to help anyone. After you go through the list, or use a structured interview, what you end up with is what the patient said when they first came through the door, "I’m depressed." And that’s how I’ve always experienced the DSM-III and later – no help…

But there’s one thing that I’ve been thinking along the way that I haven’t said – my biggest criticism of all. I don’t think Dr. Spitzer had any belief that psychiatrists help people. His quirky time as an adolescent in the Orgone Box of the disturbed Wilhelm Reich didn’t help him. His own analysis and his work with analytic patients apparently were equally ineffective. Thereafter, he was in a Biometric Department where he worked on research projects or diagnostic criteria. Nowhere in that do I hear that he was a clinician who had the opportunity to actually help patients. He took us through two profession-changing revisions of our diagnostic criteria, the criteria we use to figure out how to help people with mental illnesses, and I find nothing in his story, his career, or the classifications he gave us that says he knew what the diagnostic criteria were actually supposed to accomplish. It was like he was classifying butterflies, a collector. And his lumping of depressed people, the most common category of people we see, into either Bipolar Illness or Major Depression is the best example of that. There’s nothing in the criteria that helps clinicians know how to help anyone. After you go through the list, or use a structured interview, what you end up with is what the patient said when they first came through the door, "I’m depressed." And that’s how I’ve always experienced the DSM-III and later – no help…

The answers to the implicit questions in the criteria don’t even illuminate what the person is experiencing or give any sense of why a person might feel that way or, as you say, what might be done about it.