Ten-Year Trends in Quality of Care and Spending for Depression

1996 Through 2005

by Catherine A. Fullerton, MD, MPH; Alisa B. Busch, MD, MS; Sharon-Lise T. Normand, PhD; Thomas G. McGuire, PhD; and Arnold M. Epstein, MD

Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011 68:1218-1226.

Context: During the past decade, the introduction of generic versions of newer antidepressants and the release of Food and Drug Administration warnings regarding suicidality in children, adolescents, and young adults may have had an effect on cost and quality of depression treatment.

Objectives: To examine longitudinal trends in health service utilization, spending, and quality of care for depression. Design: Observational trend study. Setting: Florida Medicaid enrollees, between July 1, 1996, and June 30, 2006.

Patients: Annual cohorts aged 18 to 64 years diagnosed as having depression.

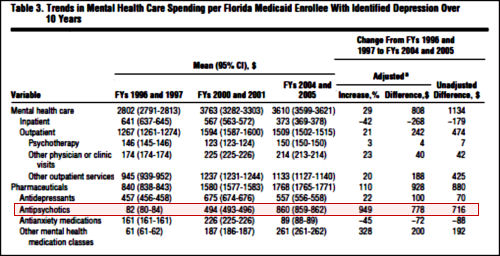

Main Outcome Measures: Mental health care spending (adjusted for inflation and case mix), as well as its components, including inpatient, outpatient, and medication expenditures. Quality-of-care measures included medication adherence, psychotherapy, and follow-up visits.

Results: Mental health care spending increased from a mean of $2802 per enrollee to $3610 during this period (29% increase). This increase occurred despite a mean to $373 and was driven primarily by an increase in pharmacotherapy spending (up 110%), the bulk of which was due to spending on antipsychotics (949% increase). The percentage of enrollees with depression who were hospitalized decreased from 9.1% to 5.1%, and the percentage who received psychotherapy decreased from 56.6% to 37.5%. Antidepressant use increased from 80.6% to 86.8%, anxiety medication use was unchanged at 62.7% and 64.4%, and antipsychotic use increased from 25.9% to 41.9%. Changes in quality of care were mixed, with antidepressant use improving slightly, psychotherapy utilization fluctuating, and follow-up visits decreasing.

Conclusions: During a 10-year period, spending for Medicaid enrollees with depression increased substantially, with minimal improvements in quality of care. Antipsychotic use contributed significantly to the increase in spending, while contributing little to traditional measures of quality of care.Submitted for Publication: December 23, 2010; final revision received June 2, 2011; accepted June 4, 2011.

Correspondence: Catherine A. Fullerton, MD,MPH, Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School.

Financial Disclosure: None reported.

Funding/Support: This work was supported by grants R01-MH081819 and K01-MH071714 (Dr Busch) from the National Institute of Mental Health. Additional Contributions: Christina Fu, PhD, providedprogramming expertise, and Laura Cowieson, BA, and Kristen Bolt assisted with research.

Online-Only Material: The Appendix and eTables are available at http://archgenpsychiatry.com.

Notice the very small print, "For adult patients with an inadequate response after at least 6 weeks of treatment with an antidepressant." What kind of approval is that, an after 6 weeks approval? For that matter, what’s with approving an XR for such a thing? The drug itself wasn’t approved. But wait! This study is on data from before 2009 when Seroquel XR was approved as an add-on for Major Depressive Disorder. It compares 1996 through 2005. Were any of the atypicals approved for Major Depressive Disorder then?

I guess not. Well, for unapproved drugs, sure are a lot of people taking them for Depression. I am, of course, being facetious. We all know that during this period, we were bombarded with people talking about treatment resistant depression and augmentation strategies for treatment resistant depression – and the new atypical antipsychotics were all the rage. It was the time when people expected the new SSRIs to work, and if they didn’t, it was considered to be another disease, treatment resistant depression, and a candidate for sequencing or commingling or augmentation. The science for such things was not particularly clear – more like alchemy – but whatever the rationale, it was what was happening in the decade the study above addressed. Words like novel or innovative were commonly used to discuss the polypharmacy that characterized the times – an era that brought us TMAP and STAR*D. But I digress. Here are a couple of abbreviated [and reformatted] tables from this retrospective study:

In case you don’t recall or maybe don’t know it, there’s a piece of this story that involves our friend Dr. Charles Nemeroff at his very worst. He was one of the prophets of augmentation with atypical antipsychotics – in this case Risperdal. He was pushing augmentation with a dog of a study under his own name [along with his later successor at Emory, Dr. Rapaport, and the often available Martin Keller of Study 329] in Nemeroff’s own journal, right at the time he got busted for other sins [VNS] and had to resign as editor of that journal – Neuropsychopharmacology. I’ve previously summarized this story [racketeer influenced and corrupt organizations…] with my title as an editorial. It’s well worth the read if you don’t know the story because it so characterizes the abject recklessness of the era [one that I’m not sure is yet ended].

As my sainted father used to say, you can’t help larfing… it makes you larf.

When I see these data I think of those cute TV ads for Abilify in depression – you know, spreading the picnic blanket. Tardive dyskinesia anybody?

This is one of those public health studies. What does psychiatry have to do with public health? All brains are different. Ya win some, ya lose some. Statistics over a population mean nothing, there were some people who were helped by the medications! There were! That’s why we have to keep medicating as many as possible. The ones who benefit justify all the cost and injury of the others. It’s only logical.

The patients using neuroleptics for depression, anxiety, insomnia, behavior control could find out the hard way what these drugs *really* are, and are capable of doing to their bodies permanently, which will make insomnia etc a welcome relief in memory hindsight ….