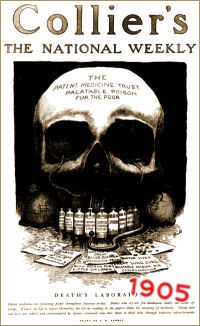

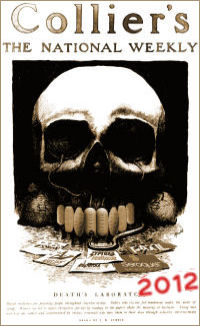

I wrote a post on the Era of Patent Medicines at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century around this time last year [patent medicine and ambiguity…]. And while this is not my definitive comment on David Healy’s Pharmageddon, it’s his book that got me going on the topic [again]. I even doctored an old Collier’s cover last year to make my obvious point:

That was early in my new-found preoccupation with what happened to psychiatry while I was so busy practicing in my cocoon and early in my retirement that I hadn’t fully noticed. And I don’t think I’d yet realized how dead on the analogy really was when I wrote that post. Beginning around the end of the Civil War, medicine-men in medicine-wagons and traveling medicine-shows scoured the countryside hawking remedies, immortalized in the figure of the Professor Marvel in the Wizard of Oz. The book was first published in 1900 in the midst of the Patent Medicine craze, and the plot hinged on the exposure of Professor Marvel/Wizard of Oz as a charlatan. To this day, "pulling back the curtain" is our preferred slang for "exposing the truth."

That was early in my new-found preoccupation with what happened to psychiatry while I was so busy practicing in my cocoon and early in my retirement that I hadn’t fully noticed. And I don’t think I’d yet realized how dead on the analogy really was when I wrote that post. Beginning around the end of the Civil War, medicine-men in medicine-wagons and traveling medicine-shows scoured the countryside hawking remedies, immortalized in the figure of the Professor Marvel in the Wizard of Oz. The book was first published in 1900 in the midst of the Patent Medicine craze, and the plot hinged on the exposure of Professor Marvel/Wizard of Oz as a charlatan. To this day, "pulling back the curtain" is our preferred slang for "exposing the truth."

So, here we sit, a century later, going through the same thing – with Patented Medicines. In his book, David Healy takes us through that history documenting how, in response to the patent medicines, physicians became the prescription writers to protect patients from the charlatans – about the reforms that lead us to clinical trials and evidence-based medicine. And then he shows us how the pharmaceutical industry co-opted all of that and has taken us back into the business of being "Medicine-Men," hawking the wares of industry – treating life and lifestyle instead of disease. The irony of the comparison with the past is interesting, but the implications are not – too on-target to ignore, too ominous to contemplate comfortably.

So, here we sit, a century later, going through the same thing – with Patented Medicines. In his book, David Healy takes us through that history documenting how, in response to the patent medicines, physicians became the prescription writers to protect patients from the charlatans – about the reforms that lead us to clinical trials and evidence-based medicine. And then he shows us how the pharmaceutical industry co-opted all of that and has taken us back into the business of being "Medicine-Men," hawking the wares of industry – treating life and lifestyle instead of disease. The irony of the comparison with the past is interesting, but the implications are not – too on-target to ignore, too ominous to contemplate comfortably.What I want to say is that I don’t like it. I never did it in practice. By some lucky fate, the patients referred to me either didn’t want that or had been through it already and given up on Patented Medicines. I wasn’t adverse to prescribing them when needed, but not as the "primary treatment." I suppose the one exception were those non-hyperactive attention deficit kids who grew up untreated and we finally figured it out in their adulthood after a few failed psychotherapies and trials of various other kinds of psychotropics before I met them. In fact, when I read about the overuse of stimulants in kids, I always think of those dramatic responses in those few adults I saw who made it through childhood without diagnosis or treatment. I guess it was just a different time.

But back to the thread of things, I now work in a charity clinic periodically where I see people for short visits. They all expect medications and are often veterans of most of the ones available. They want to list their symptoms and have me try something new. It’s harder than it used to be to get them to tell me about their lives, but they usually come around. I try to eliminate the superfluous medications and get them on something rational, or sometimes even medication free. I find a reasonable number of people who have discovered that they "can’t stop" their meds. They’ve tried and gotten sick. So I ease them off of Paxil, or Effexor, or Abilify, etc using more Benzodiazepines than I like [knock on wood – so far they come off after being detoxed without problems]. I find some people who have "diseases" like Schizophrenia, ADHD, or Manic-Depressive Illness who need medicines that are specific rather than symptomatic. I do some "country psychiatry" which is what I call rudimentary counseling, and sometimes I get to do what I know how to do. It’s rewarding enough and much needed, but talking about symptomatic meds just isn’t for me. And that’s the point of this post. I don’t like being a Medicine-Man. I may go on to argue that it’s not a good thing to be, and that David Healy has written a definitive book about how things came to be this way, and about what a disaster that is turning out to be. But those things aside, I just don’t like being a Medicine-Man. It’s not just that it’s boring, or too rote to have become a physician to spend my time with. It’s something else. I don’t believe in it.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.