The Supreme Court will take up “pay for delay” — the multibillion-dollar dispute over whether brand-name drug makers should be able to pay generic drug companies for agreeing to delay putting cheaper versions on the market. The justices agreed Friday to hear the case of Federal Trade Commission v. Watson Pharmaceuticals and two other cases to resolve conflicting rulings in lower courts. Both the pharmaceutical industry and the FTC requested a Supreme Court review to resolve a long-running battle antitrust regulators have labeled “pay-for-delay” settlements. “This is the health care reform case of 2013,” said David Balto, a former FTC policy director who helped file the first lawsuit against pay-for-delay deals back in the 1990s. “There’s no other case that can have as much impact on reducing health care costs.”

The FTC has estimated the deals cost consumers $3.5 billion annually by delaying access to cheaper generics, an estimate disputed by pharmaceutical companies. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that legislation introduced to restrict the deals would save the government more than $2.5 billion over 10 years in federal health care spending. Both the generic and name-brand pharmaceutical industries defend the settlements. They say the deals are an efficient and, from a business perspective, predictable alternative to the uncertainty about expensive patent lawsuits fought to the bitter end.

The drug industry argues that in all cases, generics come on the market before the original patents expire and sometimes sooner than they would have even in the case of a successful patent challenge. But FTC Chairman Jon Leibowitz has made the delay-deals a signature issue, arguing that they illegally prop up profits for drug companies at the expense of consumers. And in July, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 3rd Circuit sided with the FTC, upsetting more than 10 years of precedent upholding the arrangements…

The FTC challenged the settlement as anti-competitive. A district court rejected the claim. In April, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit did as well, ruling that as long as the patent settlement did not extend exclusive rights beyond the patent expiration date, it was immune to antitrust violations. The FTC asked the Supreme Court to settle the issue, and 31 states filed a brief in support of the suit. Both the generic and brand-name drug companies involved asked the high court to weigh in as well. On Friday, the Supreme Court agreed to review the cases from both the 3rd and 11th circuits.

My interest on this blog is how the business of the pharmaceutical industry massively intruded on psychiatry in the specific and the practice of medicine in general during my years as a physician. Just a piece of background: my choice of medicine had something to do with an aversion to business – well earned in early life and only moderately treatable with psychoanalysis, so the business side of things is not my forte. I owe any personal success in that arena to a good marital choice, made primarily on other grounds.

My interest on this blog is how the business of the pharmaceutical industry massively intruded on psychiatry in the specific and the practice of medicine in general during my years as a physician. Just a piece of background: my choice of medicine had something to do with an aversion to business – well earned in early life and only moderately treatable with psychoanalysis, so the business side of things is not my forte. I owe any personal success in that arena to a good marital choice, made primarily on other grounds. Once a drug is approved by the FDA, the pharmaceutical company is granted a period of exclusivity during which only they can manufacture and sell the drug – a patent with limited duration. It’s a compromise between giving them the right to profit from their investment in development and giving the consumer a break in cost with generics after the original exclusivity runs out. The company can extend exclusivity by making good faith testing in children. The obvious inadvertent consequence is that the time limit of the life cycle of a drug incentivizes the kind of deceitful marketing campaigns that minimize or even hide risk and make false claims of efficacy. It’s a sprint to achieve maximal profit in the time allowed.

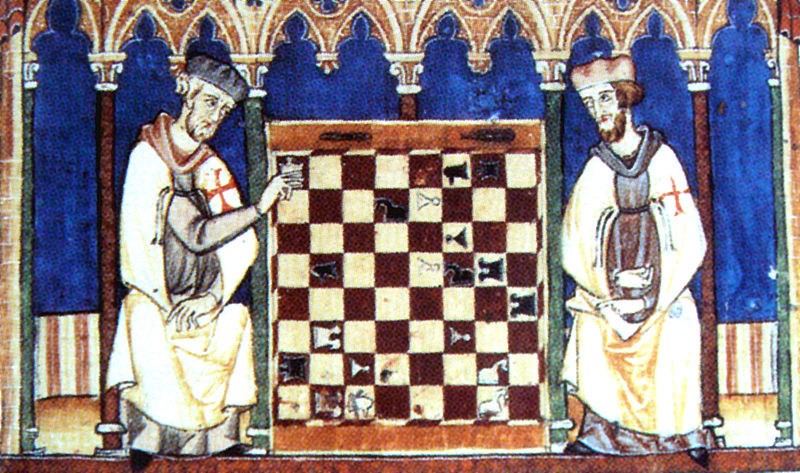

This "pay to delay" strategy seems odious to me, messing with rules clearly put in place to protect individual sick people as consumers and keep national healthcare costs in check – protecting a captive audience from exploitation. But you know what? it’s none of my business. I can make sure to only recommend drugs when indicated, and keep up with the science of safety and efficacy – using generics whenever possible to do my part in containing healthcare costs and working for my patient. But the chess game in the business arena is not my business as a physician. The covenant between doctor and patient says that I’m bringing expertise to the patient in their chess game with disease. The chess game between pharmaceutical companies and cost accounting regulators is for other experts.

But this article did bring up something that is my business. Why is the Supreme Court involved in this tedious trivia? In my mind, this is just game playing, capitalizing on a loophole. It’s worth a 15 yard penalty or some new book of statutes to close the loophole before it spreads [which it will]. But if the Supreme Court needs something to think about, why not take on the pharmaceutical industry for paying medical experts to be salesmen? or masterminding false advertizing in medical journals? or perhaps taking on participating physicians? or calling the medical profession [which claims to be self-regulating] to task for not stopping these buy-an-expert schemes? In the area of law enforcement, taking bribes or kickbacks is a crime. So is tampering with evidence. Police Departments have sections called Internal Affairs. In the practice of medicine, we have malpractice suits and people losing their licenses for stepping over ethical lines. But in academic or organized medicine, we have a subset of obviously "dirty KOLs" who seem to operate with impunity. Even when they step way WAY over the line, they are allowed to stay in the game. A recent APA President was under congressional investigation and exposed as signing on to a ghost-written textbook, one who was already in question for his involvement in a medical corporation that was all entwined with his university.

I have little interest in any more involvement of government in medicine, but without the threat of real oversight, this corruption of the covenant between physicians and patients is likely to continue. There are just too many players and too much money involved. I suppose that an analogy might be priests and other religious figures – relying on some kind of intrinsic morality to regulate things. We’ve recently seen where that kind of hands off policy has gotten us in the religious arena. The combination of the self-serving motives of the pharmaceutical, managed care, insurance, and hospital corporation industries in the practice of medicine is a international disgrace. But adding the corruption of academic and organized medicine to the mix is a multiplier of a problem already out of hand. By and large, practicing physicians and patients have become the pawns in a chess game that takes us far afield from the primary focus on the healthcare of individual patients.

I wouldn’t put any faith in the Supreme Court. They’re liable to rule “pay for delay” is another aspect of corporate free speech.

Maybe I should’ve said, “That’s what they did“…

I suppose i should mention here that by starting a trial of a medication in children, you can get six more months of patent-based exclusivity. (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21506623), which of course means that everything gets a study done on its use in children at the tail end of its patent life. oxycontin, for instance. (and not that i have an issue with giving kids pain medicine, but don’t we know just about enough about oxycodone from percocet that’s been around generically for decades?)

six months of market exclusivity is not pocket change. for some of the blockbuster drugs, that can be billions of dollars.

you do a lot of really good writing on this stuff, do you have a direct email?