One of the invariable things that comes up about psychoanalysis in any discussion is the "n=1" topic, "How can you say anything about human psychology if you only look at one case at a time? There’s no control group. No experimental group." And you’ll be pleased to learn that I’ve exceeded my lifetime tolerance for those discussions and am not bringing it up for that reason. I mention it to point out that psychoanalysts have different heros, in particular, the Ethologists, those people who approach animal and aboriginal behavior looking at one case at a time in their natural habitat. They’re those scientists like

One of the invariable things that comes up about psychoanalysis in any discussion is the "n=1" topic, "How can you say anything about human psychology if you only look at one case at a time? There’s no control group. No experimental group." And you’ll be pleased to learn that I’ve exceeded my lifetime tolerance for those discussions and am not bringing it up for that reason. I mention it to point out that psychoanalysts have different heros, in particular, the Ethologists, those people who approach animal and aboriginal behavior looking at one case at a time in their natural habitat. They’re those scientists like Sigourney Weaver Dian Fossy who spend their time doing case studies on Gorillas in the wild.

The Naturalists of the nineteenth century who were studying the variations in nature and used a different approach. Their extensive detailed observations resulted in the classifications of Botany and Zoology and laid the framework for the evolutionary schemes that followed. The later study of complex animal behavior in the natural environments couldn’t rely the carefully controlled situation of the Psychologist’s laboratory environment, so they adapted the methodology of the naturalists – making their inferences from observations without intervention. These Ethologists found validity in repeated observations of behavior patterns over long periods of time – carefully isolating similarities from the complex variability of the natural world. The Paleontologists spend their lives looking for a tiny yield – a partial skeleton here and there. But by comparing their precious pieces of evidence with each other and contemporary structures, they have produced an increasingly clear picture of man’s developmental history. And so it goes as the scientific method is adapted to the object and situation of study.

The Naturalists of the nineteenth century who were studying the variations in nature and used a different approach. Their extensive detailed observations resulted in the classifications of Botany and Zoology and laid the framework for the evolutionary schemes that followed. The later study of complex animal behavior in the natural environments couldn’t rely the carefully controlled situation of the Psychologist’s laboratory environment, so they adapted the methodology of the naturalists – making their inferences from observations without intervention. These Ethologists found validity in repeated observations of behavior patterns over long periods of time – carefully isolating similarities from the complex variability of the natural world. The Paleontologists spend their lives looking for a tiny yield – a partial skeleton here and there. But by comparing their precious pieces of evidence with each other and contemporary structures, they have produced an increasingly clear picture of man’s developmental history. And so it goes as the scientific method is adapted to the object and situation of study.

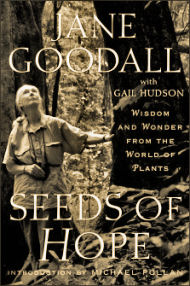

That last paragraph was plagiarized. I stole it from myself actually, something I wrote two years ago [evidence-based medicine VII: waiting for the miracle…]. And the picture is of a favorite of mine, Jane Goodall, whose study of chimpanzee behavior in Tanzania is legendary. Well, Jane Goodall is now 78 years old and has gotten herself into some hot water that has to do with plagiarism and a topic near and dear to our hearts – ghost writing. Her soon-to-be-released new book [written with Gail Hudson] has come under close scrutiny because it contains passages that are identical to [have been lifted from] other sources readily available on the Internet. It’s unfair to say ghost-written in that we presume the text was written by Gail Hudson, a common practice in the works of famous people, and Ms. Hudson is acknowledged with the standard "with Gail Hudson." But the feeling is the same – the big name at the top is Jane Goodall, and the reader visualizes Jane Goodall when they buy the book and while they’re reading it. So is this a case of our "idols having feet of clay?" We have to think about such things a bit harder when it’s our own idols under the microscope.

That last paragraph was plagiarized. I stole it from myself actually, something I wrote two years ago [evidence-based medicine VII: waiting for the miracle…]. And the picture is of a favorite of mine, Jane Goodall, whose study of chimpanzee behavior in Tanzania is legendary. Well, Jane Goodall is now 78 years old and has gotten herself into some hot water that has to do with plagiarism and a topic near and dear to our hearts – ghost writing. Her soon-to-be-released new book [written with Gail Hudson] has come under close scrutiny because it contains passages that are identical to [have been lifted from] other sources readily available on the Internet. It’s unfair to say ghost-written in that we presume the text was written by Gail Hudson, a common practice in the works of famous people, and Ms. Hudson is acknowledged with the standard "with Gail Hudson." But the feeling is the same – the big name at the top is Jane Goodall, and the reader visualizes Jane Goodall when they buy the book and while they’re reading it. So is this a case of our "idols having feet of clay?" We have to think about such things a bit harder when it’s our own idols under the microscope.

No one wants to criticize Jane Goodall — Dame Goodall — the soft-spoken, white-haired doyenne of primatology. She cares deeply about animals and the health of the planet. How could one object to that? Her list of awards and honorary degrees are too numerous to mention. She was tasked by Kofi Annan to be a United Nations Messenger of Peace, an appropriately meaningless, but distinguished, gong. In 2010, a Guardian writer noted that Goodall’s book Hope for Animals and Their World had a “written-by-committee feel of which must of course be forgiven because of its subject matter.” He felt “doubly guilty for criticising the book” when she generously inscribed his copy.You see, everyone is willing to forgive Jane Goodall. When it was revealed last week in The Washington Post that Goodall’s latest book, Seeds of Hope, a fluffy treatise on plant life, contained passages that were “borrowed” from other authors, the reaction was surprisingly muted. The writer who discovered the plagiarism—an unnamed academic reviewing the book for the Post—alerted the newspaper and backed out of the assignment. When the Post and the New York Times reported his findings, both avoided saying that Goodall had plagiarized—which, even by the strictest definition of the word, she did—instead writing that she “borrowed” passages, fully intending, apparently, to return them upon publication.

The entire controversy has been clouded in euphemism. The Post presented a half-dozen examples of plagiarism (which can be viewed here) but downplayed their significance. “Appropriating another author’s ideas as one’s own and inventing material and presenting it as fact are among the gravest literary lapses,” wrote Steven Levingston, the newspaper’s nonfiction editor. “Neither appears to have occurred in Seeds of Hope.” The Christian Science Monitor stated that “in Goodall’s case, there is no suggestion that her intent was to pass off the ideas of others as her own.” Writer Marjorie Ingall argued that Goodall (or the book’s co-author, Gail Hudson) “didn’t commit the most hellacious sin associated with plagiarism—she didn’t pass off other people’s ideas as her own.”

This is both a bizarre redefining of plagiarism and a semantic sleight of hand: Goodall quite clearly passed off the words of others as her own (and presented interview quotes said to other journalists as having been said to her). But embedded in those words is both the original author’s accumulated knowledge and, in context and arrangement, ideas. Regardless, Goodall’s offense is one that would precipitate firing from all of those publications that are rushing to provide an elastic definition of her faults.

A Jane Goodall Institute spokesman told The Guardian that the whole episode was being “blown out of proportion” and that Goodall was “heavily involved” in the book bearing her name and does “a vast amount of her own writing.” In a statement, Goodall said that the copying was “unintentional,” despite the large amount of “borrowing” she engaged in…

There is a sense in many of the reported accounts that Goodall’s co-author, Gail Hudson, is to blame. This is, of course, possible (Hudson did not respond to an email request for comment), but if Goodall had read her own manuscript—the one with her name on it—would she not have noticed the quotes from interviews with people she hadn’t spoken to? Wouldn’t a noted scientist double-check her source material? She is, after all, the person who accepted the publisher’s check and Seeds of Hope is written in the first person.

Early ethnography then took the cue from psychoanalysts when doing and conceptualizing their field work. The problem became that ethnography because a means to reify psychoanalytic thought without learning much from the perspectives of the “subjects” of study. Every person they met, every ritual, every interaction, was a way to make material a particular ideology, whether or not people saw themselves or their own communities and experiences in such a way. Just like case studies in psychoanalysis became a project in demonstrating psychoanalytic theories in a particular patient and the intellectual rigor of a the analysts doing the analytic reading, ethnographers tried to show psychoanalytic theory cross-culturally and how brilliant they were in doing so. We also know that from the beginning of analytic research, many falsehoods about patients/subjects were recorded in case study in order to better demonstrate theories, and this was also done in ethnography. I think this practice of falsification of data is always of risk when theoretical orientation with limited data able to support it tries to maintain relevancy (whether psychoanalysis, biopsychiatry or whatever).

Ethnography and cultural anthropology now in the process of a big shift of that really rejects that ethnographers can convey anything with meaning or confidence about the cultural frames in which they immerse themselves that has any intellectual or emotional honesty. Fieldwork and subsequent ethnographies has become more of a reflexive experience, where ethnographers tell a story of themselves and what they learned about their own experience through the immersion (or challenges of immersion) in a particular context. So instead of being experts on other people’s cultures, ethnographers are becoming critical thinkers of their own identities, communities, histories, and values.

Unlike psychoanalysts and mental health professionals more broadly, ethnographic fieldwork and ethnographies are not conceived as intentional interventions. While ethnographic research certainly does affect the communities where it takes place in ways that early ethnographers did not recognize or care to admit, no one believed they were health professionals trying to make lives better. Psychoanalysis never happened (or never should have happened) outside of interventionalist settings. If a psychoanalysts is only observing and writing about someone, than there is no treatment. If someone care for treatment, than this shows a lack of consent to a process. If treatment is occuring, than psychoanalysts are not just observing a case, they are actively involved in process, and when they fail to address their own persona in the research, or more importantly, do no have evidence to base treatment on, than they are doing shifty research and treatment.

So I do not have huge problems with intensive, experiential, small n research projects. There is quite a bit to learn. I do believe what is learned is not generalizable knowledge of interventions. A contemporary ethnographer is not in an ethnography likely to make universal claims about their understandings of themselves or a people, nor a methodology to intervene in fixing a kind of problem. I wish contemporary analysts would recognize this. That psychonalytic theory should not be developed through psychoanalytic treatment. Psychoanalytic theory can lead to development of psychoanalytic treatment, but that treatment should then be evaluated the way all other interventions are evaluated. Those evalautions should be used seriously to address both theory and the development of future intervention.

Cultural anthropology, astronomy, paleontology, archaeology and other observational sciences do not claim to or intent to create interventions in human life (and be paid for delivering those interventions). I don’t understand why psychoanalysis can consider itself both an observational science along the lines of those listed above, but then also claim that same science shows that they are good interventionalists.

“… you’ll be pleased to learn that I’ve exceeded my lifetime tolerance for those discussions and am not bringing it up for that reason”

Joe Hutto, a biologist, was on NRK TV last night, the national, public radio and tv-nettwork, co-starring with 13 turkey chicks in the documentary “My life as a turkey”, not saying where in the US. Judging from the scenery and a car’s number plate, they were in Florida. Not suprisingly, mr Hutto never turned into anything other than an observing, writing, posturing man, temporarily in the company of a bunch of growing, wild turkeys, all leaving for a life on their own, in due time, one Big Boy first pitching a fight. I guess wild turkey instincts told this turkey to evict the intruder-impostor-competitor from his turf. The man won, chasing Big Boy off, hitting him with a bat.

I think many of us are (in the process of) doing the same, chasing bio-psychiatrist-intruders and their masters,/cohorts in Big Pharma, APA, the Ghost-writing-industry, and Academia off, out of our lives. Enough. Time is always ripe.

The time is always ripe. But people in crisis can be helped/are helped by good therapists willing and able to listen and accompany people to greater understanding, acceptance, wisdom… It’s not about titles or methods, but sharing as best we can, what we may have evolved into. No quick fix will ever work

I’m just still trying to understand how thoroughly an investigation of biopsychiatry data and history reveals poor research ethics (fraud), poor outcomes, poor diagnostics, collusion with moneyed-powers, and claims about understanding of human wellness that are unsubstantiated by data but are always “right around the corner” when the other hegemonic historical influence in psychiatry, psychoanalysis, while showing similar practices of poor research ethics, poor research, poor outcomes, collusion with moneyed powers, and with advances always around the corner (ex. explaining past treatment failure on trauma both unknown to patients and clinicians, but when identifying it, things get better. Wasn’t this the whole basis of the devastation of repressed memory therapy?), does not get similarly investigated and critiqued. I really am desperately trying to understand this.

Berit BJ, maybe the biologist was the intruder and the turkeys were trying to fend him off, as while he thought he was just observing them, he was actually interfering in their lives in negative ways. And when they did try to assert themselves, the biologist intervened even more dramatically and violently, intervening new trauma into the live of the turkeys (and skewing the meanings of his observations and to what extent he can claim objectivity in observing). I didn’t see the documentary (itself a form of observation/intervention that is subject to critique about the meanings of experiences/phenomena between subjects, film-makers, and audience) so can’t make any strong claims.

Being an international academic celebrity is a high wire act, and famous people don’t always know when to bow out gracefully. At age 78, Jane Goodall may well be developing some cognitive slippage. That could account for such egregious and sloppy errors. Call it failure of declarative memory or call the entire episode failure of frontal lobe control, this may be the signal for her to exit the stage. I am inclined to begin with this theory over less lenient positions. I would like to continue thinking well of her, as I recall her bravery when she was taken hostage by soldiers in Tanzania in the late 1960s. Notice it is the flack catchers who surround the celebrity that are spinning the predictable lines – blaming underlings and minimizing the errors.

Our societal harshness about plagiarism arises from the notion that up and comers shouldn’t be allowed to do that for their advancement. But when you have arrived, then people cut you more slack and entertain excuses for your behavior. The celebrities buy into that idea, too – when your psychological space is Mount Olympus then ordinary rules don’t apply. Over 20 years ago a former Director of NIMH was nailed for plagiarism in several review articles. He of course tried to play it down and most of the collective frowning was directed to the whistle blower, a graduate student at U Rochester. For many of today’s KOLs in psychiatry, their psychological space is Mount Olympus but I doubt that intensive cognitive therapy would change that, so they will continue to break the rules.

Correction: Jane Goodall was not actually taken hostage when her camp was overrun by Zairean bandits. She was away from the camp on account of an illness. I stand by the comment about her bravery.