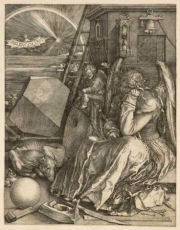

Melancholia [black bile] comes to us from antiquity, described as a temperment long before there was even the concept of disease. While I’m no expert on the topic, I’ve written about it several times [melancholia… and an ode to melancholia…]. From my vantage, it’s a unique clinical syndrome that differs from other depressions in a number of ways. I remember my thought the first time I ever saw a case: "Other depressions are adverbs or adjectives, coloring experience. Melancholia is a noun!" I’m the kind of psychiatrist that is always exploring the history for causes, but with these patients, I give up quickly. It doesn’t feel like the right thing to do. Their mood disturbance transcends anything conversational or experiential. Often they can’t describe their feeling at the time, but can talk about it later. It’s a feeling unlike grief or sadness. I gave my best shot describing it here when I was dealing with a particular case. In an editorial last year called Bringing Back Melancholia, Dr. Bernard Carrol described it in verse:

Melancholia [black bile] comes to us from antiquity, described as a temperment long before there was even the concept of disease. While I’m no expert on the topic, I’ve written about it several times [melancholia… and an ode to melancholia…]. From my vantage, it’s a unique clinical syndrome that differs from other depressions in a number of ways. I remember my thought the first time I ever saw a case: "Other depressions are adverbs or adjectives, coloring experience. Melancholia is a noun!" I’m the kind of psychiatrist that is always exploring the history for causes, but with these patients, I give up quickly. It doesn’t feel like the right thing to do. Their mood disturbance transcends anything conversational or experiential. Often they can’t describe their feeling at the time, but can talk about it later. It’s a feeling unlike grief or sadness. I gave my best shot describing it here when I was dealing with a particular case. In an editorial last year called Bringing Back Melancholia, Dr. Bernard Carrol described it in verse:

So, why does it need to be brought back? Because in 1980, it went away – subsumed under Major Depressive Disorder as a type. In prior classifications and general discussions, there were two kinds of depression – variously dichotomized Endogenous vs. Exogenous, Melancholia vs. Depressive Neurosis, Endogenomorphic vs. Characterologic. We thought of them as Depression as a disease [probably biological] and Depressive Neurosis arising from life, personality – something psychological. There was evidence moving towards defining biomarkers for Melancholia [Dexamethasone Suppression Test, Bernard Carroll; and reduced REM Latency on EEG, David Kupfer]. When the DSM-III came out, all the different depressive syndromes had been lumped together under Major Depressive Disorder. I’ve talked the why of that to death. Here are several versions [Major Depression: the orphanage…, what price, reliability?…]. The short take is that removing psychoanalysis from psychiatry was an over-riding concern in the 1980 revision, and they were afraid that any fractionation of depression at all might allow the diagnosis Depressive Neurosis to live on. So they essentially sacrificed the Disorder most likely to yield a biological etiology/biomarker in the process. That, by the way, is just my own opinion. Historian Dr. Edward Shorter put it another way in his book, Before Prozac. He concluded…

Issues for DSM-5: Whither Melancholia? The Case for Its Classification as a Distinct Mood Disorder

by Gordon Parker, M.D.; Max Fink, M.D.; Edward Shorter, Ph.D.; Michael Alan Taylor, M.D.; Hagop Akiskal, M.D.; German Berrios, M.D.; Tom Bolwig, M.D.; Walter A. Brown, M.D.; Bernard Carroll, M.B.B.S.; David Healy, M.D.; Donald F. Klein, M.D.; Athanasios Koukopoulos, M.D.; Robert Michels, M.D.; Joel Paris, M.D.; Robert T. Rubin, M.D.; Robert Spitzer, M.D.; and Conrad Swartz, M.D.

American Journal of Psychiatry 2010 167:745-747.

[full text on-line]

Melancholia, a syndrome with a long history and distinctly specific psychopathological features, is inadequately differentiated from major depression by the DSM-IV specifier. It is neglected in clinical assessment [e.g., in STAR*D] and treatment selection [e.g., in the Texas Medication Algorithm Project]. Nevertheless, it possesses a distinctive biological homogeneity in clinical experience and laboratory test markers, and it is differentially responsive to specific treatment interventions. It therefore deserves recognition as a separate identifiable mood disorder.Melancholia is a lifetime diagnosis, typically with recurrent episodes. Within the present classification it is frequently seen in severely ill patients with major depression and with bipolar disorder. Melancholia’s features cluster with greater consistency than the broad heterogeneity of the disorders and conditions included in major depression and bipolar disorder. The melancholia diagnosis has superior predictive validity for prognosis and treatment, and it represents a more homogeneous category for research study. We therefore advocate that melancholia be positioned as a distinct, identifiable and specifically treatable affective syndrome in the DSM-5 classification.

A Case for Reprising and Redefining Melancholia

by Gordon Parker, MD, PhD, DSc, FRANZCP1

Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 2013 58[4]:183–189.

Objective: To identify limitations to severity-based classifications of depression, and to argue for positioning melancholia as a distinct melancholic subtype.Method: An overview of relevant literature was conducted.Results: First, dimensionalizing depressive disorders effectively aggregates multipleheterogeneous depressive types and syndromes, and thus limits, if not prevents,identification of differential causes and treatments. Second, the melancholic depressive subtype can be defined with some relative precision, and that as it shows quite distinct differential treatment responsiveness, identification should be a clinical priority.Conclusion: Melancholia can be positioned and classified as a distinct depressive subtype.

Melancholia: Past and Present

by David Healy, MD, FRCPsych

Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 2013 58[4]:190–194.

Objective: To investigate commonalities in the clinical presentation of melancholia over time.Method: I conducted a comparative study to 2 epidemiologically complete databases from 1875–1924 and 1995–2005.Results: Patients in the historical period [1875–1924, compared with 1995–2005] with a diagnosis of melancholia show a classic profile of endogenous onset, with remission after 6 months, neurovegetative features, and, commonly, psychosis. The incidence of psychotic presentations appears to have fallen in recent decades. Patients in the contemporary period [1995–2010, compared with 1875–1924] at first admission for severe depressive disorders are more likely at an older age, more likely to go on to die by suicide, and will have much more frequent admissions.Conclusions: The data from this study support classical perceptions of melancholia. The poor outcomes in contemporary cases of severe depressive disorders support arguments for distinguishing between melancholia and other depressive disorders.

Guest Editorial

Melancholia: A Distinct Entity?

by Paul Grof, MD, PhD, FRCP

Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 2013 58[4]:181–182.

Dr. Grof’s is an editorial commentary on the two articles. I’ve clipped a couple of quotes. He also supports making Melancholia a separate diagnostic category:

"In “A Case for Reprising and Redefining Melancholia,” Dr Gordon Parker argues persuasively for melancholia being positioned as a separate, independent subtype of depression. He points out that the diagnosis of melancholic depression can be delineated with relative precision, and that it has important clinical consequences in favouring biological therapy [drug and electroconvulsive] above psychotherapy, and broad-spectrum antidepressants [ADs] over narrow-action selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Conversely, and disconcertingly, the current accretion of varied depressive syndromes under only one diagnostic umbrella precludes both targeted treatments and more productive research of the different entities. When Dr Parker1 reminds us of the limitations to current, unitary, severity-based grouping of depressions, it is hard not to agree with his argument for a separate melancholic category. The DSM symptom-based diagnoses have a century-old, historical foundation and have served satisfactorily for shorthand communication among mental health professionals and for administrative purposes. However, for what is now really needed and missing, both in practice and in research advancement, the current classification has fundamental limitations."

"However, several of the points raised by Dr Healy should be stressed and require thoughtful consideration: some statements that we now frequently read repeated in the context with contemporary depression may be considerably misleading because they were actually attained on earlier studied and -diagnosed patients with classical melancholic depressive disorder. To wit, the increased mortality rates or neuroendocrine changes connected now to major depressive disorders originated often from research on patients essentially suffering from melancholia. In practice, then, the lack of distinction between the subtypes of depression may be markedly adding to an apparent deterioration in outcome. Grouping different depressions together may also cloud the links that any of these conditions may have with physical disorders, in particular cancer or cardiovascular ailments, and may abstruse research on outcomes."

I wasn’t personally involved in all those issues – having stepped out of the main stream in the years following the 1980 revolution. So my thoughts about this are much simpler. Melancholia is a distinct clinical syndrome all unto itself. It’s an affliction, and you often know a person has it just by walking in the room. It pervades their experience, and yours too if you spend much time with them. So I start with Melancholia being an obvious separate diagnostic entity, and try to figure out why anyone would ever say it was on a continuum with the much more common depressions that psychiatrists spend their lives dealing with, or for that matter, anything else. I was an internist first, and have a lot of respect for clinical diagnosis [internists used to be called diagnosticians]. I feel kind of embarrassed that my second specialty, psychiatry, let political and other considerations get in the way of such a patently obvious distinction. It feels like a non-medical decision.

Given that how you classify depression directly determines how you treat it, I don’t think anyone would regard this discussion as a bunch of old guys hung up on nosology: Melancholic depression is treated with convulsive therapy and TCAs, non-melancholia with benzodiazepines, with such MAOIs as tranylcypromine (Parnate), and, if needs must, with SSRIs. These differences are very important. By the way, it’s ironical that, despite creating “major depression,” Bob Spitzer’s DSM-3 did not succeed in doing away with the hated “neurotic depression.” “Depressive neurosis” appeared in parentheses after “dysthymia.”

You know, that Depressive Neurosis in parentheses was never much used. Reading about it, my impression is that Dr. Spitzer put it there as a concession in his negotiations with the analysts and the neoKraepelinians during the revision process. Dysthymia had duration criteria and described a chronic illness. My impression now is that it was also created as part of a political process.

Looking back, I think the real battle in those days had to do with third party payments. The analysts had billed medical insurance for long treatments, often from the ranks of what Dr. Frances calls the “worried well.” That had to stop no matter what labels were used. So those negotiations had a background economic agenda.

I agree that had to stop. That accomplished, I’m not sure it mattered any more. In retrospect, I personally see Melancholia’s demise as collateral damage, the baby in the bathwater – and it was a real loss. Now, thirty plus years later, the real distinction is between melancholic and non-melancholic depressions and I agree with Dr. Parker, the latter is a somewhat heterogeneous group.

It seems to me that in a 21st century world, the economic conflict from those years is resolved. No third party carrier is going to pay for a long term psycho-anything treatment. I would’ve agreed with that in 1980, but the body psychoanalytic wouldn’t – and didn’t. They had enough power back then to put up quite a fight, one that they lost the day the DSM-III was published.

I worry that a very similar thing is going on now, that somehow reviving Melancholia and the distinction between melancholic and non-melancholic depressions threatens the KOL academic/pharmaceutical complex as it has developed over the past thirty years. If Melancholia returns, it weakens all of their chatter about biological underpinnings, chemical imbalance, disturbed connectomes, genomics, proteonomics, etc. and puts them in the position of having to prove their case. In Dr. Healy’s paper in the Canadian Journal, he says:

I can think of no other reason for the DSM–5 Task Force to ignore this issue [which they did]. They need Melancholia inside of Major Depressive Disorder to borrow its “biological-ness” to support their ideology [and sponsors]. At least that’s the best I can come up with. They’re now treating the large cohort of the “worried well” themselves – with pills [sometimes dangerous pills].

Thanks for commenting.

How does psychiatry label human suffering?

Let us count the ways.

Duane

I’d like to hear ‘Talking Rock Creek’.

Duane

Mickey, I’m assuming you took histories— were those you identified as Melancholic always that way? As children? I don’t doubt that people can BE in a state so completely that it IS them; but I have to wonder if it might be the result of a developmental disability— the result of an insult or injury to the brain, or trauma at a very young age that prevented the formation of architecture to help regulate mood. Or even having a primary care giver that didn’t teach the child how to regulate their mood through mirroring and soothing.

The left brain/right brain does tend to skew toward positive moods in those with a dominant left hemisphere (the smiling kid in the Special Olympics) , and negative moods in those with a dominant right (the kid that you don’t see in the Special Olympics), right? Or has that been completely debunked?

If Melancholic people are helped by drugs, then it would be very useful to identify them apart from others labeled as “depressed,” especially in clinical trials. The trouble with making a category too broad, is that after the debunking, the baby is likely to be thrown out with the bath water.

The commenter called Edward Shorter above is incorrect in that “non-melancholia” should be treated with benzos various antidepressants. Only severe depression is supposed to be treated with antidepressants. Depressed mood is a side effect of benzos, so no gain there.

I had a grand mal seizure while discontinuing a benzo as instructed. I can attribute my one and only ambulance ride, my first IV, and my only CAT scan to a benzo.

My mother (who suffered unspeakably severe abuses as a child) had been prescribed Valium since she was 16 years old. Later in life, I figured out that those times she insisted it was Wednesday and I had to convince her it was Friday, for instance, that she was most likely having blackouts from Valium, and from Valium and rum. As a child, I found those lapses were very frightening to me.

In order for the benefits to outweigh the risks, I think that a lot of options should be eliminated before a benzo is prescribed and there had better be an extreme situation to justify prescribing them for long term use.

There were some efforts to outlaw benzos at one time in the U.K., I think. One could hope that that effort led to more discriminating use of them.

I think what Edward Shorter is saying is that “melancholia” is not the only type of “severe depression” that warrants using some medication — there may be a couple other varieties that are serious, stubborn and possibly biological. Am I right in this? Or is any depression that is “non-melancholic” best seen as time-limited and non-life-threatening?

I am with Wiley and Altostrata in feeling like there had better be damned good reasons for prescribing ANY of this stuff for long-term use. One of the bass-ackwards virtues of some of the older antidepressants is that they make people so groggy, spacey, uncomfortable that no one could persuade patients to be on them “for life.” As a temporary gateway out of pure hell they have their uses, however. You just have to recognize you have moved from Hell to Limbo, and your goal is to get the Hell out of Limbo.

Likewise both booze and benzos can help some people survive an acute crisis. But both can be addictive, depressive and brain damaging, and should be watched carefully so that people in crisis don’t get hooked. Unfortunately, while liquor is considered a demon drug no one is watching the Klonopin Kabinet these days; the stuff is prescribed like candy, even to recovering alcoholics. There used to be a joke in AA circles years ago: Did you hear? Medical science has finally found the cause of alcoholism. It’s a Valium deficiency!

They used to say benzos were basically alcohol in pill form. Did everyone forget?

Some people are recreational antidepressant users. A placebo high? But, yes, Johanna the good drug/ bad drug thing denies the mind and mood altering properties of so many psychoactive drugs.

I’m contemplating my directive for mental health treatment, should I ever break down or have another psychotic break. First, I only want to be treated at the V.A. hospital. They’re used to having a lot of male soldiers that have been in combat, so they speak more respectfully to patients and the women employed there don’t do saccharine, condescending, near baby-talk with the patients. And they don’t act paranoid about the possibility of suicide, at all times, or treat any patient like a walking time-bomb.

Second, I want a big dose of benzos to put me to sleep, and adequate pain medication for my MS, so I can get all the sleep I need. Out of concern for the substance abuse problem I didn’t have, at the local hospital, I was only allowed an analgesic and a muscle relaxant for the nerve pain that had been keeping me awake for a week. I had been taking morphine. Because of what they shot me up with and the pills they gave me while I was under the influence of that caused me to lose all but three brief memories of my first two days on the ward. THAT made me feel crazy. After that, I refused the anti-psychotics two or three times a day until I left.

I didn’t know what the cocktail they gave me did to me until I saw a new patient— who very lucidly told me a lot of things about herself the night before—drooling, incapable of speaking, shuffling around like a zombie. The woman wasn’t upset, wasn’t particularly emotional, was engaging and perfectly conversational. So they doped her to the gills.

I guess I can see why someone would want a 5 megaton tranquilizer, but sheesh— popping Klonopin sounds extreme to me. Then again, the way an alcoholic can drink enough to poison the average person is pretty extreme.

“So, for what it’s worth, I see this single question as the eye of the storm. Are we going to start with the patients as they present themselves to us? Or”…?

The Timeless Question – for all not lost in the wilderness beyond the patients, for all who stay on narrow roads, who remain true to her/him-self and the patients in a world dizzy with quick fixes, waiting for the arrival of …. the glittering future…?

The human condition is not easily pinned down into diagnostic categories. I know people labelled with the major diagnosises of SMD, one after another, to grasp and simplify the chaos and the mortal wounds perpetrated on us vulnerable humans by forces beyond our control, by the ignorance and hubris of others, by oppressive poverty, wars, violence, vulcanoes, tsunamis, accidents, suicides, .. wounds that may impact future generations, as witnessed by scared descendants of American Indians, African Americans, Veterans, survivors of “lesser” evils, of which the magnitude of biological psychiatry is yet to be universally recognized.

Calamity, violence, hunger, war is visited on pregnant women and their offspring, the next generations, also presenting as … Melancholia?

Native Americans, or First Nations, more correct, I think, for the descendants of the tribes living on the American continent before the arrival of European settlers who visited treachery, genocide, continuing discrimination on the original inhabitants, and the same to enslaved Africans.

The raw emotions brought on by cruelty and injustice live on, seen in books and families, as in mine, grandmothers living through two world wars, losing brothers and sons, children crippled by want. They always seemed sad, serious, took refuge in religion, quiet ladies whose surviving children bore many scars.

When little babies and children live in war torn wars across the Middle East.

Are they suicidal?

Of course not.

The human will to live is as obvious as obvious and Seroxat, Prozac and all the rest and the depersonalisation of Benzos are a cruel cult of cruelty.

We do not do suicide……….pills do suicide….

Pills, little pills, in little boxes, all the same…..they are not all the same and ‘give us strength’ that we can all pursue a spurious arguement, coming from Pharma, that we are worn, torn, babies and children in a war zone who don’t want to live.

We want to live, equally, and pharma are not now equal to anything resembling fact from fiction…

Shame on them.

Keep the spirit of life – pills have had their day…..let;s live…..now and forever….no more pills………

Oh, the differences of “scared” and “scarred” – scarred descendants … we all are, I think, more or less.

Just to inform readers, did you know when Xanax first came out, it was touted as not only NOT a risk for benzo withdrawal (really!), but was being considered as an antidepressant? Wow, the sheer arrogance of a company trying to sell a pill!

Yeah, and the above commenter who notes that benzos are alcohol in a pill, well, I commented on that at my blog earlier this week. Really, benzo addicts are as annoying and disruptive as alcoholic patients denying recovery.

Really makes ya feel melancholic? Have a nice weekend.