by Pat BrackenWorld Psychiatry. 2014 13[3]:241-243.…

TOWARDS HERMENEUTICSI contend that good psychiatry involves a primary focus on meanings, values and relationships, both in terms of how we help patients as well as identifying from whence their problems arise. This is not to deny that psychiatry should be a branch of medicine, or that other doctors sometimes deal with problems of meaning. However, interpretation and "making sense" of the personal struggles of our patients are to psychiatry what operating skills and techniques are to the surgeon. This is what makes psychiatry different from neurology. When we put the word "mental" in front of the word "illness", we arc demarcating a territory of human suffering that has issues of meaning at its core. This simply demands an interpretive response from us. 1 think that many psychiatrists would recoil from the idea that they should train themselves to be uninterested in the problems of their patients, as the New York Times interviewee described.Hermeneutics is based on the idea that the meaning of any particular experience can only be grasped through an understanding of the context [including the temporal context] in which a person lives and through which that particular experience has significance. It is a dialectical process whereby we move towards an understanding of the whole picture by understanding the parts. However, we cannot fully understand the parts without understanding the whole. The German philosopher H.-G. Gadamer suggested that the idea of hermeneutics is particularly relevant to the work of the psychiatrist.

By adopting a hermeneutic approach to epistemology, we can attempt to understand the struggles of our patients in much the same way as we attempt to understand great works of art. To grasp the meaning of Picasso’s Guernica, for example, we need to understand what is happening on the canvas, how the artist manages to create a sense of tension and horror through the way he uses line, colour and form. We also need to understand where this painting fits in relation to Picasso’s artistic career, how his work relates to the history of Western art and the political realities of his day that he was responding to in the painting. The meaning of the work emerges in the dialectical interplay of all these levels and also in the response of the viewer. The actual physical painting is a necessary, but not a sufficient, factor in generating a meaningful work of art. A reductionist approach to art appreciation would involve the unlikely idea that we could reach the meaning of a painting through a chemical analysis of the various pigments involved.

CONCLUSIONI do not believe that we will ever be able to explain the meaningful world of human thought, emotion and behaviour reductively, using the "tools of clinical neuroscience". This world is simply not located inside the brain. Neuroscience offers us powerful insights, but it will never be able to ground a psychiatry that is focused on interpretation and meaning. Indeed, it is clear that there is a major hermeneutic dimension to neuroscience itself. A mature psychiatry will embrace neuroscience but it will also accept that "the neurobiological protect in psychiatry finds its limit in the simple and often repeated fact: mental disorders are problems of persons, not of brains. Mental disorders are not problems of brains in labs, but of human beings in time, space, culture, and history."hat tip to Mad in America…

For most of my career, I was comfortable with the term «mind·brain dichotomy». Actually, it wasn’t anything I gave much thought. It was just a descriptor – a way of separating two areas that I knew something about. I didn’t pay attention to the «mind·brain dichotomy» part, as in mutual exclusivity or contrast. My primary interests were in the «mind·brain dichotomy» part, but that didn’t mean I didn’t care about the «mind·brain dichotomy» part. I was certainly aware that in the halls and meetings of psychiatry and psychology, this was a true «mind·brain dichotomy» and the controversy was endless. Mainstream psychiatrists like APA presidents and NIMH Directors were careful to always say brain diseases or even clinical neuroscience, and critics raled against the bio·bio·bio medical model. I frankly thought it was all a bunch of turf fighting with the many psychiatrists asserting their "medical·ness" and way overdoing the whole neoKraepelinian thing, perpetuating their war with the psychoanalysts, and the critics were on the same tack as Dr. Szasz and the 1970s behaviorists. The battling feels anachronistic, like straw man arguments, to me, and I try to avoid it whenever possible in line with my life rule, "never accept an invitation to go crazy."

But as an older retired psychiatrist, I have had other thoughts. I now think that explicitly or implicitly dichotomizing brain disease or human psychological processes is only destructive, and that it is a «false dichotomy» in the end. I personally think that the psychotic mental illnesses are likely biologically determined, or at least have prominent biological determinants. I don’t know that like I do about Systemic Lupus Erythematosis [SLE], but it’s what I think. I would be likely to use medications in cases of psychotic illness, but not because I think I’m treating the underlying cause. I would be using them because psychosis can be disruptive to the person’s life and sometimes fatal, and the medicine can help with that. I’m way on the side of using medications only when there’s a reason and not as a maintenance. The drugs are too toxic for maintenance and there’s increasing evidence that less is better in the long term [I think of Lithium as an exception to that statement]. I think the same thing about Lupus. Steroids or immunosuppressives don’t treat whatever Lupus is [like Vitamin C treats Scurvy]. They treat the damage to the body by suppressing the pathological immunological mechanisms. Antipsychotics can suppress psychotic damage, also a mechanism of disease. The analogy goes further in that. Both steroids and antipsychotics are toxic, dangerous, and not for casual or prolonged use. But that has nothing to do with the minds of these patients. I happen to think many patients with the schizophrenic illnesses are candidates for a kind of psychotherapy adapted to their specific mentation – and that it involves their learning to live with the difficulties in abstraction, emotional experience, and their propensity to psychotic reactions in the face of life’s confusions. Those patients have minds too and often need [and want] help with some aspect of their mental life, on meds or not [by the way, adaptive counseling often helps Lupus patients live with their illness as well\.

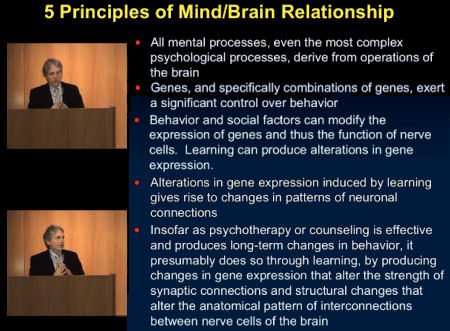

So as much as I like Dr. Bracken and as much as I agree with "I do not believe that we will ever be able to explain the meaningful world of human thought, emotion and behaviour reductively, using the "tools of clinical neuroscience", and even though I say things like that sometimes, I’m trying to get over doing it. And as much as I am infuriated when Dr. Nemeroff flashes slides that say things like this implying that he knows something the rest of us don’t:

I say let him think what he thinks. I doubt that many are listening much anymore.

I realize that in this piece, Dr. Bracken is reacting to people like Dr. Nemeroff, Dr. Insel, and many of the mainstream psychiatrists who have dehumanized psychiatry and tried to make an unleapable leap. He’s part of a group that call themselves the Critical Psychiatry Network for that very reason. But I think they make a mistake to even engage with those people on the other side, as destructive as they can sometimes be. There are destructive forces on both sides [and will be so long as the notion of "sides" persists]. Dr. Bracken and others in this group have so much to teach us, to restore a rational balance, but not by arguing with the caricatured enemy. The biologists and neuroscientists have much to teach us too, at least some of them do, and I look forward to learning about it when they get it straight.

My favorite book is called Collections of Nothing by William Davies King. Every mental health professional — indeed, every human being should read it.

Yes, it rambles, much as we all do, and circles back on realizations, which should come as no surprise to anyone who is introspective. For much of this short book, you’ll be trying to figure out the author’s degree of mental health. Ultimately, it’s a beautiful explication of an ordinary confused life as art.

Throughout the book, which is intensely personal, the author does not mention his profession. He has been a professor of theater for decades, with a special interest in the existentialists. (He’s recently extended his work to the Web, see http://williamdaviesking.com)

It doesn’t appear to me to be impossible that some psychotic disorders have a brain/genetic cause or relation because everything must. The primary problem I have with psychiatry embracing genetics like a brother, is that they are brothers. What seems to be understood by the most serious researchers in genetic research that psychiatry so embraces is that it’s primarily oversimplified bunk.

The more that is learned from serious genetic researchers, the more it’s learned that it’s all far more complex than is given credit for by popular scientists (scientificists) like Dawkins and Pinker, and it’s genes/environment all the way down.

There are also huge procedural problems with GWAS, like the fact that the subjects of study have been drawn from different labs using different methods and much of it not being equally accurate.

And even those diseases/disorders with physical or genetic causal factors, don’t require medication for life in every person who suffers from it. People suffering from psychotic illness who want medications and want better medication administered better deserve such, I won’t argue with that; but I think the field of genetics is in its larval stage and is need of the same a**whipping as the MRI abusing sect of neurology. And psychiatry is exactly what you’ve discovered it to be. Many people who have made the mistake of surrendering to it, including myself, are sorry we did.

Six minutes of nuclear war in real-time, psychiatry, my childhood family— that’s the order. The first convinced me that nuclear war is a crazy symptom of a human pathology that is completely batshit insane. My family convinced me they were crazy. Psychiatry had me convinced that I was crazy.

Shouldn’t our mind/brain/social construction/genetics be extraordinarily complex? We haven’t evolved to the point of studying ourselves in such minute detail by way of a little bit of code.

And furthermore! (I’m ready to meet on a field of onions, now ; ) )

Attachment.