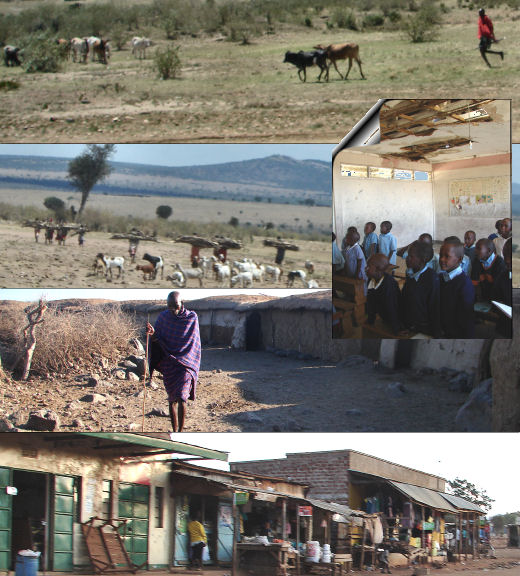

It’s hard for me to get out of Africa in my mind. It was such a compelling experience. While we went to see the animals, what lingers is the place itself and its people. Our guide said on the first day, "Safari doesn’t mean vacation, it means journey." He was certainly right about that. We flew to JFK, spent the night, then flew fourteen hours to Dubai, and four more hours into Nairobi. Nairobi has to be the most chaotic place on the planet – people and cars moving about in large numbers seemingly at random. There were rare traffic signals – most intersections were round-abouts with cars jockeying for position. Officially they drive on the left side of the road, but that seems to be more a suggestion than a habit. Outside the city, the roads are abysmal. When paved, there are constant potholes and frank breaks in the pavement, but much of the trip was on rippled and rutted dirt roads unequalled by anything even here in our rural South. While downtown Nairobi has stores and buildings like other cities, elsewhere the small towns in Kenya and Tanzania seemed more like flea markets – filled with homemade shacks containing small shops, all arranged on the raw African soil. In between the towns, Maasai men and boys dressed in traditional clothing drove small herds of cattle while the women either carried bundles of gathered wood or had plastic buckets full of water carefully balanced on their heads. The Maasai are herders – living on meat, blood, and milk. They eat nothing that comes from the ground. Their villages are circles of huts made from a mixture of dirt and dung that hardens into a water-proof leathery covering. The cattle spend the night in the center of the settlement with a separate pen for the goats.

When I look at these pictures, I see primitive and poverty. But that’s not how it felt when I was there. It just felt like a very different way of being. All of our travels were in the Maasai tribal areas. There are no fences or land ownership – cattle graze freely everywhere. While they live as they’ve always lived – many have been to government or mission schools. I saw nothing of the broken spirit of poverty. Rather, they seemed a proud people living in a structured society. And they were as curious about us as we were about them.

A school we visited had 600 students and 9 teachers. In the picture, there’s a lightbulb in the classroom, the only one I saw in the school. It’s for the upperclassmen [eighth grade] to study at night for their qualifying exams for high school. In the school, there weren’t many girls, and the number decreased in each higher grade. Maasai girls are given in marriage early, and taken out of school. Maasai circumcise men and girls as a rite of passage – the latter is now called "genital mutilation." This school boards forty girls who have been taken away from their parents to spare them this fate. They live in a cloakroom sized room in the back of a classroom. Each girl has a metal box for belongings and a mat to sleep on in a classroom floor at night. On the one hand, it seemed tragic. On the other, the pride of the teachers and students in making a dent in this ancient culture was palpable.

I had a very strange and confusing set of feelings, shared by most of the people in our group. I wanted to put this place in some familiar context, and to do something to help them move closer to the world as we know it. We were advised not to give in to the impulse to make donations or pledges of support because whatever we gave would disappear and never reach the children. If we wanted to give financial support, we were told how to make donations in a way that didn’t get lost in some black hole of corruption. But all that was balanced by another emotion – something like respect, maybe even awe, for this very foreign way of living a life. But without really thinking about it, I was caught up in the differentness of the Maasai.

At one point, we were leaving Amboseli, a dried up ancient salt lake below Mount Kilimanjaro that has aquifer-fed swamps teeming with wildlife – oases in an otherwise barren dusty desert [Amboseli is an anglicized version of an African word that means "salty dust"]. As we drove across the desert, we could see the line after line of Maasai herding their cattle along the horizon’s mirage heading for the swamps. Then we came upon four men sitting alone in the desert around a calf who was obviously ill.

Our driver/guide, Ruben, an educated man who had spent several days fascinating us with his discussions of the wildlife and the geography of the area drove off the road to the four men. They discussed things in Kiswahili for a while. When we drove on, Ruben told us that the calf was sick and had been given medicine by the men who would stay with the calf until it either died or revived – protecting it from predators [spears at hand]. It was obvious that our guide and these men were peers. Ruben had stopped because he shared their concern for the calf as well as being concerned for their well-being. I’m sure he would have loaded them onto our van had they wanted to leave the calf and the desert. Something about this exchange between Ruben and these Maasai warriors broke the spell of differences I had been feeling earlier. There was no gulf between this modern, well-spoken city-dweller, Ruben, and the Maasai herders. They were just African men talking about a situation before them. I think earlier, the Maasai were so far outside my experience, I must have been viewing them as aliens – an absurd idea I’d have been ashamed of if I’d been aware I was thinking it. To Ruben, they were just some guys who might as well have had a flat tire and he was stopping because he’s a helpful person.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.