PsychiatricNewsby Mark MoranSeptember 24, 2015Separate codes should be created for the care-management and psychiatric-consultation components of the collaborative care model. Appropriate payment codes need to be developed to reflect the work of physicians — including psychiatrists — participating in collaborative care models treating patients with mental illness in primary care settings, said APA CEO and Medical Director Saul Levin, M.D., M.P.A., in a letter last month to the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

The 18-page letter was in response to CMS’s Proposed Rule for Medicare Program; Revisions to Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Revisions to Part B for CY 2016. The letter addresses a range of issues raised in the proposed rule — including improving payment accuracy for primary care and care management services, chronic care management and transitional care management services, the Physician Quality Reporting System, electronic health records, and the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act. But the bulk of APA’s comments in Levin’s letter focused on payment and coding issues around reimbursement for the collaborative care model [CoCM]. The model, developed by leaders in integrated care at the University of Washington, involves a primary care physician, a care manager, and a psychiatric consultant.

“The lack of reimbursement for key components of this model has been the principal barrier to its widespread implementation,” Levin stated. “Although there may be other treatment models that engage primary care clinicians and behavioral health specialists, the specific Collaborative Care Model [referenced in the proposed rule] is the only model that has compelling scientific data supporting its effectiveness. Over 80 randomized, controlled trials have shown the CoCM to be more effective than care as usual. … In addition to the robust research evidence for the value of collaborative care, there is also substantial practice experience with this model of care from the Medicaid-funded Mental Health Integration Program in Washington State, the commercially funded DIAMOND program in Minnesota, and similar programs in several other states.”

The letter continued, “[T]he development of codes and requirements to be used for collaborative care for behavioral health conditions must be specific to the CoCM to enable its clinical approach and processes. To create codes that would facilitate any or all of the clinical roles or transactions embedded in the model [such as co-location of a care manager and screening mechanisms] without being tied to the other elements of the model [such as measurement-based care maintained in a registry with psychiatrist oversight] will not realize the substantiated results of the model’s utilization: that is, better quality patient care and outcomes and cost efficiencies”…

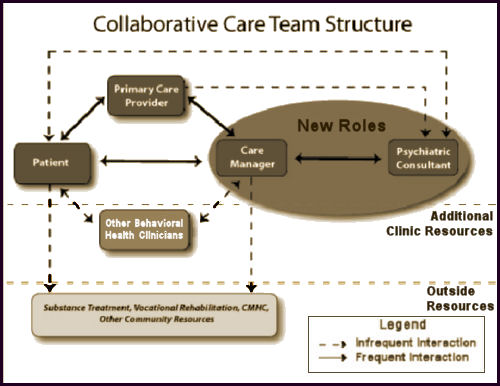

It remains hard for me imagine that anyone takes Collaborative Care as it is being presented seriously or would willingly participate. It begins [top version] with a Primary Care Provider who sees the patient and "Makes initial diagnosis and prescribes medication." So right out of the gate, the model is based on the premise that a symptomatic diagnosis of mental illness should lead to a medication prescription. The patient then gives symptom updates to the Primary Care Provider and the Case Manager. At some point, the Case Manager discusses the patient’s progress with the Psychiatrist, and the Psychiatrist makes treatment [medications] recommendations. In the second version, there are provisions for the Psychiatrist or other Behavioral Health Clinicians to have infrequent interactions with the patient.

We’re further down that yellow brick road than we used to be. We know that none of the current psychiatric drugs are benign and that their efficacy is nowhere near what has been widely advertised. We also know that these medications are grossly over-prescribed and many, if not all, can have a withdrawal syndrome that can be problematic. The majority of people who come to a clinic complaining of psychiatric symptoms have some problem in their life, and could benefit from a talk with someone who understands people [I work in such a clinic, and I’m impressed that one can get a lot done even with short and infrequent visits].

-

keep the Primary Care Provider from using the medications as badly as they are currently being used

-

certify that the patient is receiving psychiatric care

Not just the APA.

http://www.aacap.org/app_themes/aacap/docs/advocacy/policy_resources/preparing_for_healthcare_reform_201303.pdf

Collaborative care also happens to be the main policy interest of the incoming AACAP president.

Of course collaborative care really has nothing to dow with psychiatric care:

http://real-psychiatry.blogspot.com/search/label/collaborative%20care

It is all about streamlining the prescription of inexpensive generic antidepressants and it was designed to take psychiatrists out of the loop. In this managed care model people can be “treated” for less than a hundred bucks a year in generic antidepressants. Being as politically clueless as they are the APA and their CEO think that they can now muscle back in and get some reimbursement for waving their hands over this algorithm. They don’t understand managed acre and why this approach was invented in the first place.

Definitive proof that the APA does little to represent working psychiatrists and what they do. I can think of a handful of people I have seen over 30 years who could be handed a checklist and treated on that basis. But even then – it could not be predicted ahead of time. Then again, I am interested in talking about and treating psychiatric problems. I am not a busy FP trying to diagnose and treat a multitude or ambulatory complaints in too little time.

To add a little BOM color, the Diamond Project that looked at the PHQ-9 in primary care clinics in Minnesota was sponsored by ICSI and ICSI of course is sponsored primarily by the managed care companies in the state:

https://www.icsi.org/about_icsi/members__sponsors/

Thanatos

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Death_drive

Remarkably nonstrategic and self-destructive for a group of people who pride themselves on thinking about the meaning of their behavior.

This is just so far from what I do for a living — and we wonder why there is a shortage of psychiatrists. Why would anyone who wants to be a physician be happy with a career where they are always a few circles on a Venn Diagram away from ever speaking to a patient? Talk about an unrewarding model for both they psychiatrist and the patients.

And what happens to the person who needs to or wants to get off of psych meds thanks to this “wonderful” collaborative care model? Who supervises the taper?

Sadly, since so many physicians (not all) are clueless about withdrawal issues, I see this problem getting alot worse. A big fat sigh.

What happens when you want to get off is you can if you have enough money to get individual attention.

ACA was designed to produce equity in healthcare, the predictable unintended effect is the same as public schools. The wealthy opt out and everyone else is trapped.

But let’s not look at that, let’s fawn all over the good intentions of its supporters.

Which is how you assess the performance of a small child, not an adult.

Dinah,

I’m trying to take it seriously [which isn’t easy] and read up on it. It’s slow going because there’s so much jargon. If you’re interested, this is the definitive version from 2013 -> The Collaborative Care Model: An Approach for Integrating Physical and Mental Health Care in Medicaid Health Homes…

Rather than getting off the medications – the primary consideration is how many people are started on these medications who do not need them. My guess is that it is a large number – people taking them for adjustment disorders, drug and alcohol problems, and chronic life stressors that won’t go away until they make some changes.

You generally won’t find that number by looking at how the collaborative care model is studied. You will only find positive studies.

Also agree with Dinah here – no need for psychiatrists anymore – just “prescribers”. It’s a win-win for managed care. No need to hire “expensive” staff or spend much on medications or psychotherapy.

Hi Mickey,

I posted my own suggestion for an antidote to this on MIA today.