| The great eventful Present hides the Past; but through the din Of its loud life, hints and echoes from the life behind steal in. |

| John Greenleaf Whittier |

I grew up in the 1940s in a reasonable family – not much inundated with religion or superstition. But there were still some things to complain about – Cod Liver Oil for example. Never was there such a vile substance, but my otherwise sensible mother administered it with a too-generous tablespoon on a regular basis. There were a few other things – Castor Oil regularly applied to warts [with no results that I could see]. When I complained, I heard stories of the "spring cleanings" with "phospho-soda" [a cathartic that packed a wallop] or the soaps-suds enemas of their childhoods. So I was to feel lucky. My next door neighbor’s family was less modern. The "spring cleanings" still went on, and the medicine cabinet was full of tonics and remedies with labels that looked as if they’d come from some ancient time. My friend there had the Saint Vitus Dance and spent a year in pajamas being pampered with toys and ice cream [and plenty of tonic]. His older sister had jaw-lock which meant she would bite down on her toothbrush and her jaw would lock up [causing her to stay home from school]. Only my mother could relieve the dreaded jaw-lock [with soft words and soothing massage]. When I asked my Mom about her technique, she just smiled.

I grew up in the 1940s in a reasonable family – not much inundated with religion or superstition. But there were still some things to complain about – Cod Liver Oil for example. Never was there such a vile substance, but my otherwise sensible mother administered it with a too-generous tablespoon on a regular basis. There were a few other things – Castor Oil regularly applied to warts [with no results that I could see]. When I complained, I heard stories of the "spring cleanings" with "phospho-soda" [a cathartic that packed a wallop] or the soaps-suds enemas of their childhoods. So I was to feel lucky. My next door neighbor’s family was less modern. The "spring cleanings" still went on, and the medicine cabinet was full of tonics and remedies with labels that looked as if they’d come from some ancient time. My friend there had the Saint Vitus Dance and spent a year in pajamas being pampered with toys and ice cream [and plenty of tonic]. His older sister had jaw-lock which meant she would bite down on her toothbrush and her jaw would lock up [causing her to stay home from school]. Only my mother could relieve the dreaded jaw-lock [with soft words and soothing massage]. When I asked my Mom about her technique, she just smiled.

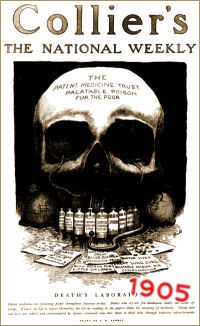

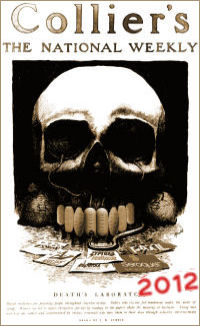

I ran across this stuff while I was nosing around to see when the FDA [and Physicians] became the gatekeepers, but the Patent Medicine story adds a perspective to the current debates about psychotropic medications. It has all of the elements of today’s story: the promise of relief from life’s ills; corporate greed and false advertising; muckraking. But now there are some other things in the mix – Clinical Trials, the FDA, FDA approval, Physicians, Medical Journals, Pharmaceutical Conglomerates, Insurance Plans, Diagnostic Manuals, Academic Medicine, CME presentations, blogs, etc. [I guess things don’t really change very much, they just get a lot more complicated]. So are we just repeating history? Are the raft of new expensive medications that have a lot of us so upset simply a repeat of the Patent Medicine era of bygone days? Are the Speaker’s Bureaus just modern snake oil salesmen and traveling medicine show hucksters hiding behind white coats and medical licenses? Or are they even more dangerous because some of these medications have the capacity to do some serious damage? Is it time for some new version of Collier’s to do a centennial issue on "The Great American Fraud Revisited?"

I ran across this stuff while I was nosing around to see when the FDA [and Physicians] became the gatekeepers, but the Patent Medicine story adds a perspective to the current debates about psychotropic medications. It has all of the elements of today’s story: the promise of relief from life’s ills; corporate greed and false advertising; muckraking. But now there are some other things in the mix – Clinical Trials, the FDA, FDA approval, Physicians, Medical Journals, Pharmaceutical Conglomerates, Insurance Plans, Diagnostic Manuals, Academic Medicine, CME presentations, blogs, etc. [I guess things don’t really change very much, they just get a lot more complicated]. So are we just repeating history? Are the raft of new expensive medications that have a lot of us so upset simply a repeat of the Patent Medicine era of bygone days? Are the Speaker’s Bureaus just modern snake oil salesmen and traveling medicine show hucksters hiding behind white coats and medical licenses? Or are they even more dangerous because some of these medications have the capacity to do some serious damage? Is it time for some new version of Collier’s to do a centennial issue on "The Great American Fraud Revisited?" Some aspects of today’s situation do sound like the days of the Patent Medicines. I think about them every time I see one of those "Ask your Doctor if ___ is right for you" ads [mercifully, very few patients have ever asked]. But, in the main, our modern problem has a more ominous underpinning than in the days of the morphine tinctures or the alcohol based tonics, particularly in the area of the modern psychoactive medications. The Food and Drug Act of 1906 established the FDA, a government agency, to certify the effectiveness and safety of medications released on the market. This blog and many others document numerous examples where the FDA has either been given inaccurate information or relevant data has been withheld in the approval process. There are even a few allegations where the FDA process has been corrupted from the inside. Too many academic psychiatrists have been on the marketing side of Pharmaceutical Companies, and there’s an epidemic of physicians being paid by drug companies to give Continuing Medical Education presentations. Both universities and private physicians are part of a cottage industry doing drug trials – many with only marketing objectives. A few years back, you couldn’t tell who was in the pocket of some drug company. Now, it seems hard to find someone who isn’t. The same is true of many of our Journals, apparently filled with ghost-written articles [in collusion with pharmaceutical representatives].

Some aspects of today’s situation do sound like the days of the Patent Medicines. I think about them every time I see one of those "Ask your Doctor if ___ is right for you" ads [mercifully, very few patients have ever asked]. But, in the main, our modern problem has a more ominous underpinning than in the days of the morphine tinctures or the alcohol based tonics, particularly in the area of the modern psychoactive medications. The Food and Drug Act of 1906 established the FDA, a government agency, to certify the effectiveness and safety of medications released on the market. This blog and many others document numerous examples where the FDA has either been given inaccurate information or relevant data has been withheld in the approval process. There are even a few allegations where the FDA process has been corrupted from the inside. Too many academic psychiatrists have been on the marketing side of Pharmaceutical Companies, and there’s an epidemic of physicians being paid by drug companies to give Continuing Medical Education presentations. Both universities and private physicians are part of a cottage industry doing drug trials – many with only marketing objectives. A few years back, you couldn’t tell who was in the pocket of some drug company. Now, it seems hard to find someone who isn’t. The same is true of many of our Journals, apparently filled with ghost-written articles [in collusion with pharmaceutical representatives].

We all know where the solution to the immediate problem lies. If Astrazeneca had to forfeit its Seroquel profits for burying Study 15 or if GSK had to do the same for jury-rigging the suicide or dependency problems with Paxil, things would change. At the least, drugs that turn out to have been approved based on hanky panky ought to be immediately withdrawn and reevaluated. Drug trials that make sense for patients instead of patent extensions or ad campaigns would be a welcome improvement. Likewise, if Dr. Nemeroff were banned from NIH Grant money for life and shunned by academic medicine for being a Principle Investigator on a NIH Grant studying Paxil while serving on the GSK Advisory Board and being hyper-active on their Speaker’s Bureau [without reporting his income], that would end his particular flavor of sponsortizing in short order. I don’t have a solution for the CME problem. I expect there is one, but if CME is simply going to be a conduit for pharmaceutical advertising, we probably ought to do away with it altogether, at least in Psychiatry [they could just send us all flyers like they used to]. But it’s not like the days of Patent Medicines. This time, we already have most of the rules we need. They just haven’t been enforced.

A very long time ago, I had a discussion with a colleague, someone who was a champion of a new, medical psychiatry. I was arguing that we Psychiatrists occupied an odd place in medicine, that we were the doctors of ambiguity [I made that up at the time]. Every case was different, a new puzzle, and we brought the forces available to the table – all of them double edged swords – trying to find the best solution that didn’t do more harm than good. It was always a double bind. The more we knew, the more likely our success. He argued that what I was saying was unscientific and unreproducible. I countered that it was the essence of the scientific method. I claimed that if there came to be a safe, effective drug for symptomatic depression, you wouldn’t need Psychiatrists to give it [maybe not even Physicians]. And so it went – back and forth. Obviously, there was a lot more behind that discussion than meets the eye. He was a new Chairman, who became a Dean [and also a CEO of a Healthcare System]. I was an already resigned, soon to be private practitioner, headed for the world of n=1 – teaching as a volunteer. Had it been a divorce, the grounds would’ve been irreconcilable differences. As it played out, we both had rewarding careers.

What was wrong with what I was saying is that I wasn’t willing to compromise with the coming of Managed Care, or the death of the Community Health Movement, or the intrusion of the Pharmaceutical Industry. That sounds lofty and principled, but it wasn’t just that. I didn’t see those things as my problem, so I was of absolutely no use in the fight to fund a struggling Department of Psychiatry at a time when it was increasingly impossible. What was wrong with what he was saying is obvious. He became a Dean and hired his own replacement who funded things just fine [and became one of the paradigms for everything that’s wrong right now]. I would hope that my old Chairman is as dismayed about what has happened in Psychiatry as I am.

There is no perfect way for Psychiatry to proceed, but there never has been. The history of the specialty is like that of any medical discipline – a story of exciting new treatments that then begin to show their undersides. What’s different this time is that pharmaceutical money actually succeeded in buying a place at the top of the hierarchy – Chairmen of Departments, a President of our Professional Organization, some of our prominent authors, the editors of some of our Journals, many "key opinion leaders." The corruption rolled downhill, as it does. The downside of some lucrative pharmaceuticals was actively hidden from view – hidden from Psychiatrists as well as Primary Care Physicians. So the usual checks and balances on sloppy or dangerous medicine were subverted, on purpose.

I’ll challenge your choice of cod liver oil as the vilest substance ever. In the deep South in the 1930s, all us kids had to take chocolate syrup was supposed to disguise the bitterness of the quinine, but all it did was ruin the taste of chocolate for me. It took years to get over.

My maternal grandfather was a wonderful, gentle horse and buggy doctor; but his tightly corseted, Germanic wife ruled the medicine cabinet. The first line of attach against any illness — sore throat, upset stomach, whatever — was a big dose of Epsom salts — to cleanse the bowels and get rid of toxins.

Then along came Sal Hepatica, which wasn’t quite so bad. I used to plead, “Let me take Sal Hepatica instead,” when the glass of epsom salts was forced on me.

And, as you say, this is where medicine advertising came along. In the 1930’s Bristol-Meyers had two big products that were sponsors of popular radio programs: Ipana toothpaste and Sal Hepatica — Ipana to give your face a smile and the other one to give you “the smile of health.”

Thanks for prompting the memories. And for your cogent analysis of this whole pharma mess.

opps — a line got deleted. It was supposed to read: “All us kids had to take cocoa quinine throughout the summer to prevent malaria. The chocolate syrup . . .”

If “Sal Hepatica” was the desirable alternative, you indeed have my sympathy for surviving the 1930s. On the other hand Ralph, I’ve always admired your “youthfulness.” Do you reckon the “Sal Hepatica” might have helped with that?