I wrote that last piece in the spirit of full disclosure. This business of the changes that occurred in psychiatry thirty years ago remains almost as contentious today as when it happened, and it’s impossible to read anything about what people write about it without wondering about the authors’ orientation and history. I thought it would be sensible to put my story first and let you decide for yourself how contaminated my opinions are. My story is atypical in that my primary identity was doctor, and I was dissatisfied with the the fact that 3/4 of my patients had physical symptom but no "disease" – instead problems in life/mind. So the way Psychiatry was when I came fit my needs just fine. When Psychiatry changed, I considered going back to Internal Medicine as an "informed" Internist, but I guess I was hooked and found plenty to occupy my time. But what I’m trying to do right now is look back at what the DSM III framers thought they were doing, and what actually happened when they did it.

Around the time that the DSM II came out, there was a flurry of activity from multiple foci to scientificize psychiatric diagnosis – but the center of it was at Washington University in Saint Louis. In 1972, a former resident, John P. Feighner, published some of the criteria developed in seminars there as

Research Criteria:

Diagnosis has functions as important in psychiatry as elsewhere in medicine. Psychiatric diagnoses based on studies of natural history permit prediction of course and outcome, allow planning for both immediate and long-term treatment, and make communication possible between psychiatrists and other physicians, as well as among psychiatrists themselves. Such functions are of obvious importance in research. In contrast to the American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM-II], in which the diagnostic classification is based upon the "best clinical judgement and experience" of a committee and its consultants, this communication will present a diagnostic classification validated primarily by follow-up and family studies.

Over the next decade, the group there continued this approach, applying it to the Affective Disorders, Depression, Schizophrenia, Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders, Anxiety states etc. They saw this effort as an extension of the one used by Emil Kraepelin 75 years before, and their collective work had a huge influence on the DSM III committee.

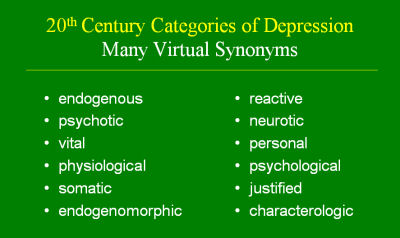

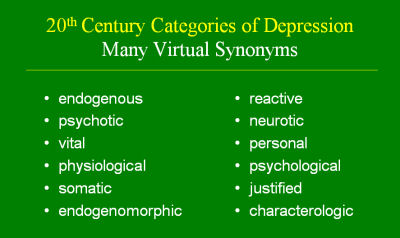

There was one particular line of thinking at the time that related to Depression that deserves mention – the widely held idea that there were two kinds of Depression. Endogenous Depression [a non-precipitated syndrome most of us thought was biologic] and Neurotic Depression [related to life events and/or the personality of the sufferer]. Here’s a slide passed along from the time by Dr. Bernard Carroll showing the various synonyms used for this distinction:

It was a concept that fit my clinical experience, so I both bought it and taught it. I think most of us did. It apparently didn’t fit the Wash U model so it didn’t make it into the DSM III. Here’s what the DSM III actually ended up saying:

And then in a footnote to the word Melancholia, it would go on to say:

A term from the past, in this manual used to indicate a typically severe form of depression that is particularly responsive to somatic therapy. The clinical features that characterize this syndrome have been referred to as "endogenous." Since the term "endogenous" implies, to many, the absence of precipitating stress, a characteristic not always associated with this syndrome, the term "endogenous" in not used in DSM-III.

This is from a letter dated February 19, 1979 from Dr. Carroll to Dr. Spitzer making a last minute plea to include the endogenous [endogenomorphic] category [thx to Dr. Carroll for passing it on]:

Obviously, his letter fell on deaf ears. I would like to think that the move to scientificize psychiatric diagnosis was only what they said it was, but I had an experience in those days that told me otherwise.

I stayed at Emory for a year after deciding to leave while my office was being built, and during that year ran the medical student teaching program. The new chairman and the old director had a falling out and I’d taught the sophomore course already, so it became my mustering out job. I went to the national meeting of such people that year in Chicago. At one series of sessions, I was sitting next to a guy who was the director of the program at Wash U. He was nice enough and we talked about Chicago etc., but he was nervous about his own talk later in the session. When he got to the podium, he commenced a rant with the fervor of a Southern Evangelist – raging against the evils of Psychoanalysis. He used words like "heresy," "dogma," "ideology," and built in intensity to the point that I thought he was heading for an altar call for us all to be born-again. Some analyst in a full Cleveland [white belt and white shoes] rebutted lamely and the discussion was beyond heated [and beyond rational]. My thought at the time? "I’m glad my town house is almost finished."

I stayed at Emory for a year after deciding to leave while my office was being built, and during that year ran the medical student teaching program. The new chairman and the old director had a falling out and I’d taught the sophomore course already, so it became my mustering out job. I went to the national meeting of such people that year in Chicago. At one series of sessions, I was sitting next to a guy who was the director of the program at Wash U. He was nice enough and we talked about Chicago etc., but he was nervous about his own talk later in the session. When he got to the podium, he commenced a rant with the fervor of a Southern Evangelist – raging against the evils of Psychoanalysis. He used words like "heresy," "dogma," "ideology," and built in intensity to the point that I thought he was heading for an altar call for us all to be born-again. Some analyst in a full Cleveland [white belt and white shoes] rebutted lamely and the discussion was beyond heated [and beyond rational]. My thought at the time? "I’m glad my town house is almost finished."

In my last post, I talked about the political and economic forces involved in the DSM III. There were certainly scientific issues on the table too, but it was no less ideological than it had been before. The Saint Louis group had Dr. Spitzer’s ear, and they were taking no prisoners. Even biological psychiatrists like Dr. Carroll [and many others] were marginalized in the process. In fact, as I recall it, the Wash U opinion, while loudly stated, was actually in the margin itself in those days. That’s one of the reasons the DSM was something of a shock when it was all said and done. Although the emerging trends in Psychiatry in those days were definitely heading in the "medical" direction, the version that appeared in the green book came neither from consensus nor even the middle, it came from a specific focus that wasn’t all the way in left field [but it was close]. The

framers were well pleased with the result:

According to Gerald Klerman, the highest-ranking psychiatrist in the federal government at the time, the movement from the DSM-I and II to the DSM-III was a “victory for science” [Klerman, Vaillant, Spitzer, & Michels]. Melvin Sabshin, the executive officer of the American Psychiatric Association, called it a great triumph of “science over ideology” [Sabshin, 1990]. For the proponents of the DSM-III, “the old psychiatry derives from theory, the new psychiatry from fact” [Maxmen, 1985]. According to another prominent diagnostic psychiatrist, “scientific evidence” rather than the charismatic authority of “great professors” stood behind the classificatory systems of the DSM-III and subsequent DSM-IV [Kendler, 1990].

I stayed at Emory for a year after deciding to leave while my office was being built, and during that year ran the medical student teaching program. The new chairman and the old director had a falling out and I’d taught the sophomore course already, so it became my mustering out job. I went to the national meeting of such people that year in Chicago. At one series of sessions, I was sitting next to a guy who was the director of the program at Wash U. He was nice enough and we talked about Chicago etc., but he was nervous about his own talk later in the session. When he got to the podium, he commenced a rant with the fervor of a Southern Evangelist – raging against the evils of Psychoanalysis. He used words like "heresy," "dogma," "ideology," and built in intensity to the point that I thought he was heading for an altar call for us all to be born-again. Some analyst in a full Cleveland [white belt and white shoes] rebutted lamely and the discussion was beyond heated [and beyond rational]. My thought at the time? "I’m glad my town house is almost finished."

I stayed at Emory for a year after deciding to leave while my office was being built, and during that year ran the medical student teaching program. The new chairman and the old director had a falling out and I’d taught the sophomore course already, so it became my mustering out job. I went to the national meeting of such people that year in Chicago. At one series of sessions, I was sitting next to a guy who was the director of the program at Wash U. He was nice enough and we talked about Chicago etc., but he was nervous about his own talk later in the session. When he got to the podium, he commenced a rant with the fervor of a Southern Evangelist – raging against the evils of Psychoanalysis. He used words like "heresy," "dogma," "ideology," and built in intensity to the point that I thought he was heading for an altar call for us all to be born-again. Some analyst in a full Cleveland [white belt and white shoes] rebutted lamely and the discussion was beyond heated [and beyond rational]. My thought at the time? "I’m glad my town house is almost finished."

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.