“The time has come," the Walrus said,

“The time has come," the Walrus said,“To talk of many things:

Of shoes··and ships··and sealing-wax··

Of cabbages··and kings··

And why the sea is boiling hot··

And whether pigs have wings.”

It seems like only yesterday, but it’s been three years since the DSM-5 was released [May 18, 2013]. Unlike Spitzer’s 1980 DSM-III, Kupfer and Regier’s DSM-5 was hardly cause for celebration. I was just glad to have it off of the front page. While the debates and harangues had gone on for years, the substantive questions about its basic structure were never even really addressed.

So when I saw the abstract below, I perked up. Dr Kendler was part of the DSM-5 Task Force and maybe he’s finally getting around to examining the flawed MDD category. However, in the days leading up to the DSM-5, Dr. Kendler wrote a report explaining the move to get rid of the Bereavement Exclusion in the DSM criteria for Major Depressive Disorder that I thought was an ill advised rationalization at best. My take is cataloged in

depressing ergo-mania….

American Journal of Psychiatry

by Kenneth S. Kendler

Published online: May 3, 2016

How should DSM criteria relate to the disorders they are designed to assess? To address this question empirically, the author examines how well DSM-5 symptomatic criteria for major depression capture the descriptions of clinical depression in the post-Kraepelin Western psychiatric tradition as described in textbooks published between 1900 and 1960. Eighteen symptoms and signs of depression were described, 10 of which are covered by the DSM criteria for major depression or melancholia. For two symptoms [mood and cognitive content], DSM criteria are considerably narrower than those described in the textbooks. Five symptoms and signs [changes in volition/motivation, slowing of speech, anxiety, other physical symptoms, and depersonalization/derealization] are not present in the DSM criteria. Compared with the DSM criteria, these authors gave greater emphasis to cognitive, physical, and psychomotor changes, and less to neurovegetative symptoms. These results suggest that important features of major depression are not captured by DSM criteria. This is unproblematic as long as DSM criteria are understood to index rather than constitute psychiatric disorders. However, since DSM-III, our field has moved toward a reification of DSM that implicitly assumes that psychiatric disorders are actually just the DSM criteria. That is, we have taken an index of something for the thing itself. For example, good diagnostic criteria should be succinct and require minimal inference, but some critical clinical phenomena are subtle, difficult to assess, and experienced in widely varying ways. This conceptual error has contributed to the impoverishment of psychopathology and has affected our research, clinical work, and teaching in some undesirable ways.

I found this abstract confusing. I couldn’t quite land on what he was getting at. I thought the idea of surveying the textbooks historically for their take on the symptoms of depression was clever. At the end, I couldn’t agree more that people have reified the DSM Disorders, or that there’s a categorical error in the woodpile with MDD. But his main point eluded me, so I read the whole article. Alas, neither of those things is what Dr. Kendler seems to be getting at here.

What I think he’s saying is that the fully nuanced clinical picture of Major Depressive Disorder may have many of the features he found in his textbook review that are being overlooked, symptoms like depersonalization or derealization. He tells us that the DSM criteria are simply an index to the Disorder, not the Disorder itself – ergo, there’s nothing wrong with the DSMs per se. The problem is a conceptual problem in the users. I guess he thinks we’ve gotten sloppy. And he apparently buys that there is a unitary Disorder behind these various symptoms. That’s hardly the serious look at Major Depressive Disorder I had hoped to read.

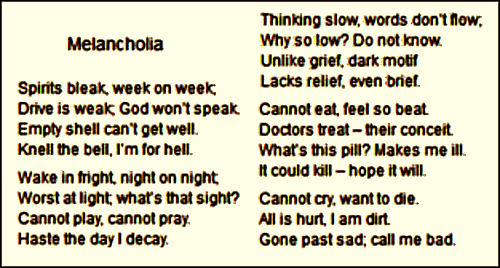

The categorical error that I see is that Major Depressive Disorder [MDD] isn’t a category in the first place, and never has been. When I think back to the 1980 days when the DSM-III first arrived, that’s what I thought on first reading. Gone was the psychiatric disease Depression, AKA Melancholia AKA Endogenous Depression AKA Endogenomorphic Depression. This is the stuff of psychiatry proper that has been with us since the dawn of recorded history. And then there used to be something else – a heterogeneous collection of patients with widely varying severity who had the affective symptom, depression, but not the illness Depression. The DSM [-I] had used the term depressive reaction. The DSM-II gathered them together under the term depressive neurosis. In the DSM-III, they were all included under MDD [my mistake, there were other categories included but they never caught on because they felt too made-up].

It’s easy to see the problem. There are really no boundaries on the much larger second group. I personally thought at the time that this second group had problems in their relationships, or their lives, or carried over from the past, or in the basic structure of their personalities, and that depression was a symptom, a signal to them and to the world that something wasn’t right. Most of my internal medicine colleagues looked into the symptoms that brought them to a doctor’s office. Finding no underlying physical cause, they reassured them and sent them on their way. I did that too, and for many, that was enough. But for a sizable number, it wasn’t, and I got interested in working with those cases [I still am]. So in that group, the gamut runs from unhappy in a lousy marriage to structuralized lifelong personality disorder. No clear borders. And that drives actuaries and third party payers crazy. So I suppose that conflating the Depressions and the severe depressions looked like a solution to many. Major Depressive Disorder then became a way of certifying or validating illness. That’s the only explanation I could come up with at the time for the faux category.

We all know what happened. Instead of tightening a boundary, the DSM-III loosened it [maybe better said, destroyed it]. So the valuable research on Melancholia was stymied by dilution, and the huge number of symptomatically depressed people became fair game for the pharmaceutical industry and the [carpetbagger] KOLs who jumped at the chance to annex them as an eager market for the antidepressants. The scientifically sound ideas that were developing about Melancholic Depression [that it has a biologic basis, that it responds to medications or ECT, that it is a brain disease, that it has a genetic component] flowed into the whole population of people with depressive symptomatology who were told they had a chemical imbalance or a brain disease. And what flowed out was untold billions of dollars in sales of largely unnecessary and sometimes dangerous medications. And in the mix, millions of dollars of unnecessary and unproductive research depleted the funds available for continuing research pathways that might have clarified some more focused piece of the puzzle. In the process, progress in the psychological and social treatments also ground to a halt. We all went backwards.

Dr. Kendler’s offering seems to be an attempt to help us be more forgiving about the short-comings of the DSM and its Major Depressive Disorder category. What I’m able to follow about his idea seems trivial and off the mark – more "cabbages and kings". I found it particularly annoying that this is one of the few commentaries on the DSM-5 from an official and that it continues to skirt the real problems. In my opinion, as shepherds of the DSM, it would behoove he and his colleagues to take another tack. Fix the DSM rather than us, and restore the boundaries to more reasonable scientific domains so we can pick up where we left off 36 years ago and bring some kind of much needed clarity to the current sea of misinformation. And as a corollary, the place of medication in the symptomatic treatment of depression can only be clarified by clinical trials conducted without the epidemic corruption of our current era. The fact that the pharmaceutical industry, the clinical trial industry, and the  third party carriers like things just the way they are right now is really not our concern.

third party carriers like things just the way they are right now is really not our concern.

So like Lewis Carroll’s Walrus, I think "the time has come … to think of many things." But right now, we’re sure not thinking about the right ones. We’re in the "whether pigs have wings" range. Somewhere on the other side of the morass of commercial interests, ideological differences, guild wars, and a sea of other bias, there’s some system that will deliver the best we’ve got with the resources available. And there’s some path that allows productive researchers to be in an environment that optimizes progress. Neither of those things are likely to happen without a sensible classification system that fits a lot better than the one we have now, without an insistence on honesty in the science we bring to bear on the problems, and without an oversight function that insures that we never again allow what’s happened here to repeat.

The

The

Again, the vicissitudes of multivariate factor analysis are well beyond capabilities of this mere mortal [namely me], but it identified two distinct clusters that had little overlap as shown in the graphic representation of their main results table from the reanalysis of Lewis’ data on the right. They had this to say about Aubrey Lewis’ papers:

Again, the vicissitudes of multivariate factor analysis are well beyond capabilities of this mere mortal [namely me], but it identified two distinct clusters that had little overlap as shown in the graphic representation of their main results table from the reanalysis of Lewis’ data on the right. They had this to say about Aubrey Lewis’ papers:

In my last post I was, once again, going on about what I see as a fundamental flaw in the DSM-III carried forward to today. My persistence in stressing the categorical distinction between Melancholic Depression and depression as a symptom was originally born from my own clinical experience but has come to have other determinants. I suspect that the "lumping" of all depression into Major Depressive Disorder [MDD] was originally a move to get the analysts out of the picture [eliminating depressive neurosis] and a concession to the insurers who have no interest in paying for symptoms arising from "life." But it had pervasive and ominous consequence. The emerging Academic·Industrial alliance co-opted the research being done on Melancholic Depression that was beginning to edge towards a neuro·biologic causality [a promising bio·marker, sleep abnormalities, response to biological treatment, the genetic component, etc] and teleported those findings to all depression [chemical imbalance, Clinical Neuroscience, etc]. It helped sell a lot of unnecessary drugs hurting some in the process, basically shut down a lot of research along productive lines, and wasted untold research dollars chasing neuro-whatever pipe dreams with the wrongest of cohorts.

In my last post I was, once again, going on about what I see as a fundamental flaw in the DSM-III carried forward to today. My persistence in stressing the categorical distinction between Melancholic Depression and depression as a symptom was originally born from my own clinical experience but has come to have other determinants. I suspect that the "lumping" of all depression into Major Depressive Disorder [MDD] was originally a move to get the analysts out of the picture [eliminating depressive neurosis] and a concession to the insurers who have no interest in paying for symptoms arising from "life." But it had pervasive and ominous consequence. The emerging Academic·Industrial alliance co-opted the research being done on Melancholic Depression that was beginning to edge towards a neuro·biologic causality [a promising bio·marker, sleep abnormalities, response to biological treatment, the genetic component, etc] and teleported those findings to all depression [chemical imbalance, Clinical Neuroscience, etc]. It helped sell a lot of unnecessary drugs hurting some in the process, basically shut down a lot of research along productive lines, and wasted untold research dollars chasing neuro-whatever pipe dreams with the wrongest of cohorts. Dr. Peter Kramer’s 1993 "Listening to Prozac" was a game changing best-seller with its enthusiasm for future possibilities for biological interventions – "replacing the couch with the capsule." It’s a different time now, and the antidepressants are under attack. Kramer returns with a new book, "Ordinarily Well," that again makes a case for the antidepressants. In a review/opinion piece in the Washington Post, Historian Edward Shorter commented favorably on the book, but made the argument that Kramer saw depression as a unitary condition rather than recognizing the distinction between Depression and depression [

Dr. Peter Kramer’s 1993 "Listening to Prozac" was a game changing best-seller with its enthusiasm for future possibilities for biological interventions – "replacing the couch with the capsule." It’s a different time now, and the antidepressants are under attack. Kramer returns with a new book, "Ordinarily Well," that again makes a case for the antidepressants. In a review/opinion piece in the Washington Post, Historian Edward Shorter commented favorably on the book, but made the argument that Kramer saw depression as a unitary condition rather than recognizing the distinction between Depression and depression [ Aubrey Lewis [1900-1975] was a major figure in the growth of Psychiatry in England after WWII. He was originally from Adelaide, South Australia where he took his medical degree and trained in psychiatry. Receiving a Rockefeller Scholarship, he traveled first to the US, working at the Phipps Clinic under Adolf Meyer, then to Germany, and finally ended up in London taking a position at the Maudsley Hospital in 1928. By 1936, he was appointed Clinical Director at the Maudsley. And when it was reorganized after the War, he was appointed Chairman of Psychiatry in the newly created Institute of Psychiatry at the College of London – a position he held until retiring in 1966.

Aubrey Lewis [1900-1975] was a major figure in the growth of Psychiatry in England after WWII. He was originally from Adelaide, South Australia where he took his medical degree and trained in psychiatry. Receiving a Rockefeller Scholarship, he traveled first to the US, working at the Phipps Clinic under Adolf Meyer, then to Germany, and finally ended up in London taking a position at the Maudsley Hospital in 1928. By 1936, he was appointed Clinical Director at the Maudsley. And when it was reorganized after the War, he was appointed Chairman of Psychiatry in the newly created Institute of Psychiatry at the College of London – a position he held until retiring in 1966. “The time has come," the Walrus said,

“The time has come," the Walrus said, It seems like only yesterday, but it’s been three years since the DSM-5 was released [May 18, 2013]. Unlike Spitzer’s 1980 DSM-III, Kupfer and Regier’s DSM-5 was hardly cause for celebration. I was just glad to have it off of the front page. While the debates and harangues had gone on for years, the substantive questions about its basic structure were never even really addressed.

It seems like only yesterday, but it’s been three years since the DSM-5 was released [May 18, 2013]. Unlike Spitzer’s 1980 DSM-III, Kupfer and Regier’s DSM-5 was hardly cause for celebration. I was just glad to have it off of the front page. While the debates and harangues had gone on for years, the substantive questions about its basic structure were never even really addressed. So when I saw the abstract below, I perked up. Dr Kendler was part of the DSM-5 Task Force and maybe he’s finally getting around to examining the flawed MDD category. However, in the days leading up to the DSM-5, Dr. Kendler wrote a report explaining the move to get rid of the Bereavement Exclusion in the DSM criteria for Major Depressive Disorder that I thought was an ill advised rationalization at best. My take is cataloged in

So when I saw the abstract below, I perked up. Dr Kendler was part of the DSM-5 Task Force and maybe he’s finally getting around to examining the flawed MDD category. However, in the days leading up to the DSM-5, Dr. Kendler wrote a report explaining the move to get rid of the Bereavement Exclusion in the DSM criteria for Major Depressive Disorder that I thought was an ill advised rationalization at best. My take is cataloged in  third party carriers like things just the way they are right now is really not our concern.

third party carriers like things just the way they are right now is really not our concern.