In deeply troubling…, I started in 2001 with the publication of the Paxil Study 329 paper looking at Karen Dineen Wagner’s history, but perhaps I should’ve started a couple of years earlier with the now infamous TMAP project. And then there was an appearance at a SmithKline Beechum Neuroscience Division meeting that bears mentioning…

TMAP/TCMAP

Perhaps the biggest pharmaceutical scam to date was TMAP [Texas Medical Algorithm Project]. Before it was stopped, it had nearly bankrupted the Texas Mental Health system, had spread to 17 other States, and was on its way to Washington. It should make us all shudder when we hear the word "Guidelines." It was shepherded into being by

John Rush and

Madhukar Trivedi in Dallas. Basically, they controlled guidelines for the huge Mental Health system in Texas. It had a child piece [TCMAP] and

Karen Dineen Wagner and

Graham Emslie were both involved in setting the Algorithms. The TMAP program was exposed in 2004 largely through the work of one man,

Allen Jones, an Inspector for the Pennsylvania OIG [who was fired for his work] but who never gave up. Below is just a snippet from a

report he published on the Internet in 2004 with the bare bones of Dr. Wagner’s involvement [A more complete version about her goes from pages 10-14, and

tells quite a story]:

In 1997-98, TMAP, with pharmaceutical industry funding, began working on the Texas Children’s Medication Algorithm Project [TCMAP]. An "Expert Consensus" panel was assembled to determine which drugs would be best for the treatment of mental and emotional problems in children and adolescents. The panel consisted almost exclusively of persons already involved in TMAP or associated with TMAP officials. A survey was not necessary.

These persons simply met and decided that the identical drugs being used on adults should also be used on children. There were no studies or clinical trial results whatsoever to support this consensus…

One of the members of the children’s "expert consensus panel" was Graham J. Emslie,M.D., Professor and Chair, Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, [a TMAP site] and Director. Bob Smith Center for Research in Pediatric Psychiatry, Dallas, TX…

The panel also included Dr. Karen Dineen Wagner…

In 1998, without any published trial data and based on the "consensus opinion" of Emslie, Wagner and others, TCMAP began widespread usage of these SSRIs and other drugs on children within the Texas state Juvenile Justice system and state Foster Care System…

Between 1998 and 2003, state doctors following the TCMAP guidelines routinely and regularly prescribed these antidepressant drugs to children in accordance with the TCMAP algorithm requirements…

After the first year, they published periodic updates in the JAACAP:

by CARROLL W. HUGHES, GRAHAM J. EMSLIE, M. LYNN CRISMON, KAREN DINEEN WAGNER, BORIS BIRMAHER, BARBARA GELLER, STEVEN R. PLISZKA, NEAL D. RYAN, MICHAEL STROBER, MADHUKAR H. TRIVED, MARCIA G. TOPRAC, ANDREW SEDILLO, MARIA E. LLANA, MOLLY LOPEZ, A. JOHN RUSH, AND THE TEXAS CONSENSUS CONFERENCE PANEL ON MEDICATION TREATMENT OF CHILDHOOD MAJOR DEPRESSIVE DISORDER

Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 1999 38[11]:1442-1454.

The consensus panel agreed on categorizing 3 levels of "data" hierarchically in formulating stages and differential branching of the treatment algorithm. Level A data consist of both child and adult randomized controlled clinical trials, level B data consist of open trials and retrospective analyses, and level C data are based on case reports and panel consensus as to recommended current clinical practices. Level A takes precedence over level B, and B over C…

The recommended monotherapy antidepressant for stage 1 are SSRIs [fluoxetine, paroxetine, or sertraline]. [Fluvoxamine and citalopram may be added to the list at a future date with additional research and experience]…

SSRIs are deemed first-line treatments because of supporting efficacy data for fluoxetine in children and adolescents and paroxetine in adolescents [level A], open trials of sertraline [level B], and clinical experience [level C]. Information extrapolated from adults further supports the initial use of SSRIs given the minimal need for dosage titration [level A in adults and level C in children/adolescents] and favorable side effect profiles [levels A and C]…

Only fluoxetine was a published paper [paroxetine was an abstract of Study 329 posted at the 1998 APA]. There was a

consensus meeting recorded in 1998, with no details [wayback machine].

With the coming of Jones’ whistle blower suit and the mounting awareness of adverse effects that lead to the Black Box Warning, TCMAP just disappeared. TCMAP was never adjudicated, and the only specific TMAP suit I know of was the settlement in Allen Jones and the State of Texas v. J&J.

Paxil in Pediatric Depression and «The Launch»

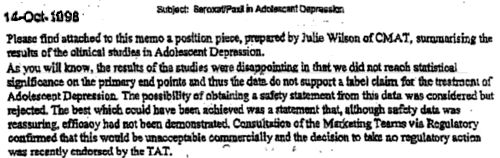

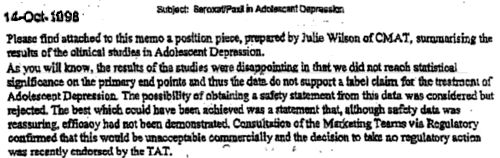

We all know about the famous Paxil Study 329, published in July 2001 in the JAACAP with 24 authors [Karen Dineen Wagner among them]. The Acute phase of Study 329 ran from 04/1994 until 03/1997 [blind broken]. In October 1998, this internal memo went out:

The draft of the paper came from ghost writer Sally Laden to First Author Martin Keller in February 1999, and by August 1999, he had submitted the paper to the JAMA. It was turned down there in November 1999. In December 1999 and again April 2000, there were emails saying that they were rethinking it, planning to go for the AJP. But in June 2000 [?], it was at the JAACAP where it was accepted in January 2001 and published in their July 2001 issue.

So what does all this have to do with Dr. Wagner? Back in Early December 1999, she was the main event for a

SmithKline Beecham meeting in San Francisco – the Neuroscience Division. Here’s their Newsletter [December 9, 1999] about the meeting [

Nulli Secundus –

second to none]. They were launching Paxil for adolescents:

"As many of you know, SB is preparing an indication for adolescent depression for Paxil next year! SB’s clinical study demonstrating the success of Paxil in treating depression among adolescents will be published in a peer reviewed journal during first quarter 2000…"

"Dr. Wagner said the window of opportunity is before SB. Several other competing SSRls and other compounds have studies ongoing. But Paxil and Prozac are the only two SSRIs that have any published data to date and many physicians have already found success in treating adolescent patients with Paxil…"

"The paroxetine study measured treatment of adolescent depression. It is the largest study to date, involving 275 adolescents at 12 sites for eight weeks. In the study, one of three treatments was possible: imipramine, paroxetine, or placebo. Results:

"As a result of this large study," Dr. Wagner said, "We can say that paroxetine has both efficacy and safety data for treating depression in adolescents."

At the time she gave this presentation, that first paragraph simply wasn’t true. SB had long before decided not to go for an indication for Paxil in adolescents. The paper had just been rejected by the JAMA – with no publication in sight. The JAMA reviewers pointed to the low HAM-D cut-off, the effect of supportive care, the high Placebo response, the small or absent differences in rating scales, the significant incidence of Serious Side Effects with Paroxetine, and the inappropriate dosing of Imipramine. For that matter. I have no clue where those results came from, not from the paper or the CSR.

At the time she gave this presentation, that first paragraph simply wasn’t true. SB had long before decided not to go for an indication for Paxil in adolescents. The paper had just been rejected by the JAMA – with no publication in sight. The JAMA reviewers pointed to the low HAM-D cut-off, the effect of supportive care, the high Placebo response, the small or absent differences in rating scales, the significant incidence of Serious Side Effects with Paroxetine, and the inappropriate dosing of Imipramine. For that matter. I have no clue where those results came from, not from the paper or the CSR.

A look at the work of one medical school researcher, Dr. Karen Dineen Wagner, shows the challenges and possible pitfalls such research can entail. For example, from 1998 to 2001, university records show, Dr. Wagner was one of several academic researchers participating in more than a dozen industry-financed pediatric trials of antidepressants and other types of drugs. While some of the results were published, many were not.

I ran across this 2004 article from the New York Times by Barry Meier [Contracts Keep Drug Research Out of Reach]. An excellent article, it prominently mentions Dr. Wagner and reminds us that this was the heyday of industry-funded Clinical Trials and that Dr. Wagner was one of a handful of Academic Child Psychiatrists who were involved with almost every study published – people who were and who remain prominent figures in the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, the organization Dr. Wagner was just elected to lead.

This is hard for me to personally understand. Dr. Wagner has essentially made her career advocating the use of psychophatmacologic agents in the treatment of children – having covered the gamut of conditions, drugs, and worked with many of the front-running drug companies who make and profit from these drugs. Surely the broad membership of the AACAP knows that, and knows about the dark side of her work – ghost-writing, financial COI, withheld negative studies, TMAP, training sessions for PHARMA. At a time when such things are moving closer and closer to the front burner, why would the AACAP membership choose her as President? Are her colleagues unaware of her history? Is that possible? Is this a sign that her position represents the consensus of the members? For that matter, why would she even run for that office instead of lowering her profile? It’s similar to the questions asked when people like Drs. Alan Schatzberg or Jeffrey Lieberman have been elected to the APA Presidency.

I don’t know the answers to those questions…

I decided that trying to summarize Why is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders so hard to revise? Path-dependence and "lock-in" in classification in the last post [a curious inertia…] was too much, but rereading it this morning, I changed my mind. Independent from how the DSMs came into being, this article has something to say about any future attempts to change it no matter what changes are proposed [and changing it yesterday would be absolutely okay with me]. As Allen Frances tweeted about this article, "DSM is so hard to change not because it’s right – it’s that every change has harmful unintended consequence."

I decided that trying to summarize Why is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders so hard to revise? Path-dependence and "lock-in" in classification in the last post [a curious inertia…] was too much, but rereading it this morning, I changed my mind. Independent from how the DSMs came into being, this article has something to say about any future attempts to change it no matter what changes are proposed [and changing it yesterday would be absolutely okay with me]. As Allen Frances tweeted about this article, "DSM is so hard to change not because it’s right – it’s that every change has harmful unintended consequence." I’m a self-taught typist with a spastic technique. I actually look at the keyboard, so I never knew why the keyboard is laid out so oddly. But in the day, fast typists could jam up pretty easily if the keybar from the last letter isn’t out of the way of the next. So the keyboard layout is designed to put keys that frequently follow each other in words far apart. Very clever! Now, that doesn’t matter with the computer keyboards, but because all jillion of you real typists out there would rise up in arms if it got changed to the Dvorak layout, it stays the same – QWERTY. And if there were a major revision of the DSM, the administrative and actuarial changes would fall into the "Y2K" range. If I may be allowed an editorial comment, the third party carriers don’t trust us to make

I’m a self-taught typist with a spastic technique. I actually look at the keyboard, so I never knew why the keyboard is laid out so oddly. But in the day, fast typists could jam up pretty easily if the keybar from the last letter isn’t out of the way of the next. So the keyboard layout is designed to put keys that frequently follow each other in words far apart. Very clever! Now, that doesn’t matter with the computer keyboards, but because all jillion of you real typists out there would rise up in arms if it got changed to the Dvorak layout, it stays the same – QWERTY. And if there were a major revision of the DSM, the administrative and actuarial changes would fall into the "Y2K" range. If I may be allowed an editorial comment, the third party carriers don’t trust us to make  reasonable treatment recommendations. Instead they force us to squeeze patients into these often ill-fitting categories with somewhat fixed coverage. The profoundly depressed Melancholic and the situationally depressed may have the same coverage – a silly use of a Dx category…

reasonable treatment recommendations. Instead they force us to squeeze patients into these often ill-fitting categories with somewhat fixed coverage. The profoundly depressed Melancholic and the situationally depressed may have the same coverage – a silly use of a Dx category…

Anybody recall what it was about? I remembered the Black Death, Joan of Arc, the introduction of the longbow in the Battle of Agincourt. As for what it was about? England v France, Kings and things – that’s about all I could remember. One thing I never knew, the distinct cultural identities of France and England, including languages, were formed and consolidated during that conflict. Apparently a good war is a powerful organizer of national unity and cultural identity.

Anybody recall what it was about? I remembered the Black Death, Joan of Arc, the introduction of the longbow in the Battle of Agincourt. As for what it was about? England v France, Kings and things – that’s about all I could remember. One thing I never knew, the distinct cultural identities of France and England, including languages, were formed and consolidated during that conflict. Apparently a good war is a powerful organizer of national unity and cultural identity.  One of my memories from early childhood was of standing in our front yard when everyone had gone crazy. People were beating on pans and shooting guns, laughing and hugging each other – my parents included. My mother noticed I was frightened, crying I think. She said something like, "Don’t worry. We’re happy. The War is over! [WWII]. But that made things worse, because I didn’t know that "War" was something that was ever "over". Where would it go? I thought war was just a part of life [actually, I think I might have been right about that at age 4]. Oh, by the way, the War of Roses started a few years after the end of the Hundred Years War.

One of my memories from early childhood was of standing in our front yard when everyone had gone crazy. People were beating on pans and shooting guns, laughing and hugging each other – my parents included. My mother noticed I was frightened, crying I think. She said something like, "Don’t worry. We’re happy. The War is over! [WWII]. But that made things worse, because I didn’t know that "War" was something that was ever "over". Where would it go? I thought war was just a part of life [actually, I think I might have been right about that at age 4]. Oh, by the way, the War of Roses started a few years after the end of the Hundred Years War.

In 1997-98, TMAP, with pharmaceutical industry funding, began working on the Texas Children’s Medication Algorithm Project [TCMAP]. An "Expert Consensus" panel was assembled to determine which drugs would be best for the treatment of mental and emotional problems in children and adolescents. The panel consisted almost exclusively of persons already involved in TMAP or associated with TMAP officials. A survey was not necessary. These persons simply met and decided that the identical drugs being used on adults should also be used on children. There were no studies or clinical trial results whatsoever to support this consensus…

In 1997-98, TMAP, with pharmaceutical industry funding, began working on the Texas Children’s Medication Algorithm Project [TCMAP]. An "Expert Consensus" panel was assembled to determine which drugs would be best for the treatment of mental and emotional problems in children and adolescents. The panel consisted almost exclusively of persons already involved in TMAP or associated with TMAP officials. A survey was not necessary. These persons simply met and decided that the identical drugs being used on adults should also be used on children. There were no studies or clinical trial results whatsoever to support this consensus…

At the time she gave this presentation, that first paragraph simply wasn’t true. SB had long before decided not to go for an indication for Paxil in adolescents. The paper had just been rejected by the JAMA – with no publication in sight. The JAMA

At the time she gave this presentation, that first paragraph simply wasn’t true. SB had long before decided not to go for an indication for Paxil in adolescents. The paper had just been rejected by the JAMA – with no publication in sight. The JAMA  A series of articles in the New England Journal of Medicine has questioned whether the conflict of interest movement has gone too far in its campaign to stop the drug industry influencing the medical profession. Here, three former senior NEJM editors respond with dismay

A series of articles in the New England Journal of Medicine has questioned whether the conflict of interest movement has gone too far in its campaign to stop the drug industry influencing the medical profession. Here, three former senior NEJM editors respond with dismay Public trust in the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industry is low. Many practising physicians share that mistrust and are inclined to discount the results of otherwise sound studies that are industry funded. There are good historical reasons to be sceptical. But has suspicion degenerated, as some have charged, into “mindless demonisation?” The New England Journal of Medicine [NEJM] seems to think so. It has published a series of commentaries and an editorial suggesting there have been serious negative consequences of strict, “oversimplified” conflict of interest and disclosure policies, including the development of a “hostile climate” and “loss of trust.” Editor in chief, Jeffrey Drazen, says the “divide” between academic researchers and industry is not in the best interests of the public because “true improvement can come only through collaboration.”

Public trust in the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industry is low. Many practising physicians share that mistrust and are inclined to discount the results of otherwise sound studies that are industry funded. There are good historical reasons to be sceptical. But has suspicion degenerated, as some have charged, into “mindless demonisation?” The New England Journal of Medicine [NEJM] seems to think so. It has published a series of commentaries and an editorial suggesting there have been serious negative consequences of strict, “oversimplified” conflict of interest and disclosure policies, including the development of a “hostile climate” and “loss of trust.” Editor in chief, Jeffrey Drazen, says the “divide” between academic researchers and industry is not in the best interests of the public because “true improvement can come only through collaboration.”