Posted on Sunday 20 April 2014

Director’s Blog: NIMHBy Thomas InselApril 11, 2014… check out a new report from the Treatment Advocacy Center on the treatment of people with serious mental illness. According to this report, there are now 10 times more people with serious mental illness in state prisons [207,000] and county jails [149,000] than there are in state mental hospitals [35,000]. The report includes a state-by-state assessment of treatment of people with mental illness in jails and prisons. In 44 of the 50 states, the largest single “mental institution” is a prison or jail…

How can this be possible? In the 1830’s Dorothea Dix revolutionized the care of people with mental illness by taking them out of jails and caring for them in asylums, later known as state hospitals. In the last 50 years, we have reversed this trend, resulting in a 90 percent reduction in public hospital beds for people with serious mental illness. While this reversal came about as the result of good intentions, it has resulted in unintended consequences. Many, but not all, people with serious mental illness can be treated effectively with the less restrictive care offered in outpatient settings. Sometimes patients with serious mental illness, just as with other serious medical illnesses, require hospitalization. In the absence of available public or private hospital beds, there are few options. Some patients are housed in emergency room holding areas; some return home, where family and friends struggle to provide care; and some—at considerable risk to themselves—become homeless. For those who do not realize they are ill and therefore resist treatment, or those whose behavior may be disruptive or aggressive, jails and prisons have become the de facto mental hospitals…

What should be done? Returning to the asylum system — which could be regarded as turning away from the goal of recovery — is not the answer. The new report suggests several remedies, including ensuring better treatment within the prison system, jail diversion programs, assisted outpatient treatment, and release planning. Surely our nation can do better than assigning the criminal justice system the responsibility for delivering care to the mentally ill. In an era of mental health parity and health care reform, how can we allow hundreds of thousands of people with a brain disorder to be treated in our justice system — if that can be called treatment — rather than our healthcare system? Abraham Lincoln, no stranger to serious mental illness, once lamented, “a tendency to melancholy… is a misfortune not a fault.” Our current system, if these new numbers are accurate, treats mental illness, for many, not as a misfortune but a crime, with little promise of recovery.

And I’m not going let go with a primal scream that those 350,000 people are not Myths. Their commitment was as criminals. They are receiving medications whether they want them or not [or whether they need them or not]. And, by the way, the TAC doesn’t need any biomarkers to know who they are or to count them. The prison guards know. The other prisoners know. The judges that sent them there know. It’s just not that hard to tell.

And I’m not going to advocate more medications, or less, or pray for future medications, or long for old Asylums, or blame psychiatrists, or anyone else. But there is something worth saying here. The National Institute of Mental Health is our government Agency that is tasked with thinking about the mental health of the country, and this is a problem that actually belongs at the very top of that problem list. There are countries all over the world that do a much better job with this problem than we do. There are social scientists and psychiatrists and social workers and psychologists all over this country that specifically care passionately about this topic and these patients. So why doesn’t the National Institute of Mental Health have a Task Force to look at this problem rationally, to travel the world looking at solutions, to figure out a direction for us to be moving in.

"Who wants to go to a doctor that is not the most well informed, the most aware of what’s happening?" Hugin said. "We really want to make sure that this act, which is designed to make things more transparent, does that but doesn’t change behavior because people misuse the data and apply in a way that implies something inappropriate." He suggested that the Sunshine Act may become an issue when and if people mischaracterize the data when it becomes public. That’s why companies and doctors must be proactive later this year when the data are released to make sure it is presented accurately and fairly, he indicated.

"Who wants to go to a doctor that is not the most well informed, the most aware of what’s happening?" Hugin said. "We really want to make sure that this act, which is designed to make things more transparent, does that but doesn’t change behavior because people misuse the data and apply in a way that implies something inappropriate." He suggested that the Sunshine Act may become an issue when and if people mischaracterize the data when it becomes public. That’s why companies and doctors must be proactive later this year when the data are released to make sure it is presented accurately and fairly, he indicated.

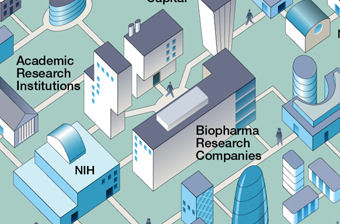

It’s an impressive universe they have there. I noticed that they left out the ghostwriters. Maybe they’re the ones walking around outside on their virtual campus. On the site, there’s something called the

It’s an impressive universe they have there. I noticed that they left out the ghostwriters. Maybe they’re the ones walking around outside on their virtual campus. On the site, there’s something called the

The

The  Their logo shows their most characteristic graph – the forest plot with the mean and Confidence Intervals of a number of trials of the same thing. The size of the mean box in the center is proportional to the size of the trial and the horizontal line shows the 95% C.I. The bottom diamond is the weighted trial mean. The horizontal axis varies depending on what’s measured. The top graph is from the Tamiflu meta-analysis and shows the time to first alleviation of symptoms between Placebo and Zanamivir. One can see the means, the intervals, the significance [does it cross the vertical null line], and the sum of all studies at a single glance.

Their logo shows their most characteristic graph – the forest plot with the mean and Confidence Intervals of a number of trials of the same thing. The size of the mean box in the center is proportional to the size of the trial and the horizontal line shows the 95% C.I. The bottom diamond is the weighted trial mean. The horizontal axis varies depending on what’s measured. The top graph is from the Tamiflu meta-analysis and shows the time to first alleviation of symptoms between Placebo and Zanamivir. One can see the means, the intervals, the significance [does it cross the vertical null line], and the sum of all studies at a single glance.