Living in the UK in the1970s practicing in an a US Air Force Hospital near one of the UK’s primo Hospitals [Addenbrooks, in Cambridge] was interesting. Suffice it to say that our systems and expectations are very different. I never quite ‘got it‘ – except to say ‘very different‘ and ‘interesting.’ I think I understand the term, ‘service users‘ in the papers I’m about to discuss. It means, ‘people who rely on the National Health Service‘ for their health care – according to Wikipedia, that’s 92%. If I understand correctly, NICE [National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence] sets treatment guidelines one of which is to offer CBT [16 sessions] to service users with Schizophrenia, but it’s not really available through the NHS. That adds a commercial element to the issues brought up by the BPS report [or I could’ve misread the whole thing].

There was the phenomenal work of Anthony Morrison, who is the first researcher to empirically show that psychotherapy can be effective with individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia, even when they choose to not take psychotropics. Although many know this intuitively, the scientific community is not really interested in intuition; for him to show this repeatedly through empirical data is profound.

by Morrison AP, Turkington D, Pyle M, Spencer H, Brabban A, Dunn G, Christodoulides T, Dudley R, Chapman N, Callcott P, Grace T, Lumley V, Drage L, Tully S, Irving K, Cummings A, Byrne R, Davies LM, and Hutton P.Lancet. 383[9926]:1395–1403

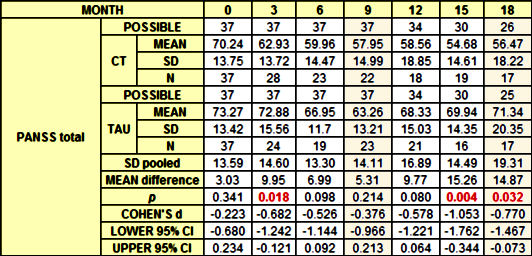

BACKGROUND: Antipsychotic drugs are usually the first line of treatment for schizophrenia; however, many patients refuse or discontinue their pharmacological treatment. We aimed to establish whether cognitive therapy was effective in reducing psychiatric symptoms in people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders who had chosen not to take antipsychotic drugs.METHODS: We did a single-blind randomised controlled trial at two UK centres between Feb 15, 2010, and May 30, 2013. Participants aged 16-65 years with schizophrenia spectrum disorders, who had chosen not to take antipsychotic drugs for psychosis, were randomly assigned [1:1], by a computerised system with permuted block sizes of four or six, to receive cognitive therapy plus treatment as usual, or treatment as usual alone. Randomisation was stratified by study site. Outcome assessors were masked to group allocation. Our primary outcome was total score on the positive and negative syndrome scale [PANSS], which we assessed at baseline, and at months 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, and 18. Analysis was by intention to treat, with an ANCOVA model adjusted for site, age, sex, and baseline symptoms. This study is registered as an International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial, number 29607432.FINDINGS: 74 individuals were randomly assigned to receive either cognitive therapy plus treatment as usual [n=37], or treatment as usual alone [n=37]. Mean PANSS total scores were consistently lower in the cognitive therapy group than in the treatment as usual group, with an estimated between-group effect size of -6.52 [95% CI -10.79 to -2.25; p=0.003]. We recorded eight serious adverse events: two in patients in the cognitive therapy group [one attempted overdose and one patient presenting risk to others, both after therapy], and six in those in the treatment as usual group [two deaths, both of which were deemed unrelated to trial participation or mental health; three compulsory admissions to hospital for treatment under the mental health act; and one attempted overdose].INTERPRETATION: Cognitive therapy significantly reduced psychiatric symptoms and seems to be a safe and acceptable alternative for people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders who have chosen not to take antipsychotic drugs. Evidence-based treatments should be available to these individuals. A larger, definitive trial is needed.

Participants allocated to cognitive therapy received a mean of 13.3 sessions [SD 7.57; range 2–26], with each session lasting roughly 1 h [these figures do not include the four booster sessions that were available]. Adherence to cognitive therapy was reasonably good, with no patients not attending any sessions, and 30 [82%] having at least six or more sessions.

… 74 individuals were randomised to the cognitive therapy plus treatment as usual group [n=37], or the treatment as usual alone group [n=37]. We stopped before the target of 80 individuals in accordance with our recruitment timeline, on the basis of restricted resources, to ensure that we had the possibility to obtain 9 month data for all participants. Baseline characteristics were similar between groups.

By examination of the proportion of participants achieving good clinical outcomes in each disorder [defined by use of an improvement of >50% in adjusted PANSS total scores], we noted that, at 9 months, seven [32%] of 22 participants in the cognitive therapy group, and three [13%] of 23 from the treatment as usual group had achieved good clinical outcomes. At 18 months seven [41%] of 17 receiving cognitive therapy and three [18%] of 17 receiving treatment as usual had achieved good clinical outcomes.

With regards to use of antipsychotic drugs throughout the lifetime of the trial, ten [4%] of 37 participants in the cognitive therapy group were prescribed antipsychotics after randomisation [eight during the treatment window and two during the follow-up phase] as were ten [4%] of 37 in the treatment as usual group [nine during the treatment window and one during the follow-up phase].

So in-so-far as I’m able to vet this study, I would see it as a pilot project showing a signal that deserves repeating, but I can’t confirm the opening quote above, the article’s conclusion, or the commentary on the article. Here’s the thing of it, my bias is on the side of confirmation. I support psychotherapeutic intervention in Schizophrenia. I’m not sure I would’ve picked CBT, but I’m not an CBT-er, and from what I can read, Morrison et al have adapted the technique to be used in this condition.

I’d like to see psychotherapy work too.

This line in your post seems relevant:

and many of the results have molded to the wishes of the sponsors rather than the data itself.

The NHS is really invested in CBT and other short-term therapies; they are the ultimate sponsor here.

I’d like to see whether other modalities are helpful as well and whether more intensive treatments are useful.

I don’t think there is any reason to wait for the ideal CBT study. I also don’t think there is any magic to CBT. There was better evidence that psychotherapy “works” for schizophrenia in the Boston psychotherapy study of schizophrenia published in the Schizophrenia Bulletin in 1984. It compared the effects of exploratory, insight-oriented (EIO) and reality-adaptive, supportive (RAS) forms of psychotherapy in schizophrenia and concluded the RAS had preferential effects. From my extensive reading of the therapy of schizophrenia, supportive therapy has significant overlap with CBT and anyone trained in supportive psychotherapy should not have any problems with that transition.

I would not hesitate to use it in cases on early onset psychosis and have used it as an adjunct to medication and in cases where the patient was not interested in taking medication. Even in cases where the patient does not follow up with the course of psychotherapy – it allows for a more complete elaboration of their problems and how they can be a focus for collaboration and resolution.

The great unknown in the US is paying for it and whether staff psychiatrists in HMOs would be allowed to do it rather than “medication management”. In my case I had to subsidize any therapy that I did with additional “productivity” in other areas. I noticed a few years ago that the average course of psychotherapy in managed care clinics was about 3 sessions and it never resembles the research version.

I noticed a few years ago that the average course of psychotherapy in managed care clinics was about 3 sessions and it never resembles the research version.

But is the amount in the research really enough either?

In terms of the type of therapy, is this an area where the diagnosis of schizophrenia is not the most meaningful determinant? Are there other personality factors and other psychosocial factors which ought to be considered?

Someone who grew up in a house where they were neglected and with poor caregiving is going to have a different set of issues from somebody who grew up in a stable home.

EastCoaster,

I think that’s right, but a decent therapist can negotiate that. In a world where the kind of therapy and number of sessions is pre-specified, that latitude is erased.

Mickey, That was part of my point.

And a good one!

The concept of even a minimal number of person to person sessions is important. The concept of check a box and then medicate is not serving us well and the need for a person to have a more complete picture of the patient and their situation is paramount.

http://davidhealy.org/antidepressants-and-the-tell-tale-heart/?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+DrDavidHealy+%28Dr.+David+Healy%29

http://davidhealy.org/antidepressants-and-the-tell-tale-heart-ii/?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+DrDavidHealy+%28Dr.+David+Healy%29

The need for a careful thoughtful analysis combined with a caring advocate who understands is in stark contrast to what we see being practiced.

A comment in the last thread stuck me when it spoke of “doctors and friends” seeing issues with patients. I would expand this to include social groups, and work dynamics.

Today we see many patients slapped with a label, medicated, and then left to navigate the changes in their emotions and mental state. Friends and co-workers are then in the position of trying to work out what is wrong and how to best help. This is not an acceptable situation given the increased stress of most work environments and the lack of training in the general population.

My issues have mostly to do with the clergy. A minister who has stated he has multiple mental health issues has surround himself with educators and social workers all trying to help, all the while he continues on a course to access a $6M endowment fund. An area supervisor who has her own set of psychopathic tendencies and lust for glory all leave me on the outside yelling the emperor has no clothes.

Like many others, including medical professionals not involved in primary care, I am left wondering if the person next to me is medicated and are they, I hope, talking with someone. The proliferation of anti-depressants given in primary care offices with no follow up has put us as a society at risk. Anti-social behaviors perpetrated by those in this state place a stigma on those needing help and raise the level of paranoia in society.

The last thing we need in today’s environment is people being afraid to speak with one another and reach out a helping hand.

Steve Lucas

This was difficult for me to read, as my own biases incline me to ignore flaws in studies that support psychosocial interventions.

So thanks, because it’s all the more important that I have a good clear analysis o the evidence.

I’d also recommend this recent review paper:

Thomas et. al. Psychological Therapies for Auditory Hallucinations (Voices): Current Status and Key Directions for Future Research

Which shows how modest the gains are in many studies (i.e. less dramatic than might be suggested by this Morrison paper) but nevertheless supports both psychosocial interventions in clinical practice and the need for further research.

East Coaster – the people I have actually treated with psychotherapy alone require more than 3 sessions. The other elements that you mentioned are included in any reasonable psychiatric evaluation usually ahead of any list of diagnoses and that formulation is what the therapy is generally based on. There is no diagnosis that determines a course of therapy – but there are clearly insurance companies that do.

The link to Hilda Bastian’s blog ‘Study Report, Study Reality, and the Gap Between’ doesn’t work currently (there’s a problem with PLOS Blogs Network). But the cached version can be accessed: http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:wQVph37qu_EJ:blogs.plos.org/absolutely-maybe/study-report-study-reality-and-the-gap-between/+&cd=1&hl=en&ct=clnk

It’s well worth a look, including the link to a highly questionable trial report http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25344629#cm25344629_6775

To get back to the study by Anthony Morrison et al that Dr. Mickey discussed: My first impression is that it would hardly be surprising to find a benefit of cognitive therapy (CT) in patients with schizophrenia diagnoses. I am baffled by the pugnacious attitudes that have been expressed – in the comments on MIA, for instance – by supporters of non-drug interventions in schizophrenia. Second, people may wish to read a series of 4 letters published August 2, 2014 in Lancet, along with a response from Dr. Morrison and co-authors. These exchanges underline the tentative nature of conclusions that are possible from Dr. Morrison’s pilot study. Dr. Mickey’s request for full data access is right on target – what’s good for the goose is good for the gander.

Next, even though the authors issued a disclaimer about not having demonstrated that CT is effective, only safe and acceptable, and then a second disclaimer in their Lancet letter stating their trial “was not designed to change clinical practice,” they nevertheless tried to wring as much mileage from this pilot study as possible. The clearest instance of that is their hortatory insistence that “Evidence based treatments should be available to these individuals.” The clear implication here is that they consider their evidence justifies a policy mandate. As Dr. Mickey’s analysis and the commenters in Lancet demonstrate, however, their data do not yet support that belief.

My chief reservation about the Morrison study, however, is that they didn’t really test what they set out to test and what they claim they did test. What they said was, “We aimed to establish whether cognitive therapy was effective in reducing psychiatric symptoms in people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders who had chosen not to take antipsychotic drugs.” The comparison was designed to be against a matched group who received treatment as usual (TAU). The confound that they glossed over was antipsychotic drug prescription in the CT group. More than a quarter of these subjects took antipsychotic drugs during the study. The authors kept this information out of the Abstract and they tried to rationalize it away in the Discussion. A good experimental design would have removed those cases as failures when antipsychotic drugs were considered necessary. It matters not that the TAU group had a similar number of cases who were given antipsychotic drugs – that’s what TAU is about, after all. Removal of those cases from the CT group would have seriously reduced the sample of completers and the consequent power analyses. Alternatively, need for antipsychotic drugs would have been an appropriate hard primary endpoint, in which case there would clearly be no difference between the two groups.

The authors’ closing interpretation was, “Cognitive therapy significantly reduced psychiatric symptoms and seems to be a safe and acceptable alternative for people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders who have chosen not to take antipsychotic drugs.” Sorry – no cigar yet.

Thanks for this summary. I also found it hard to understand this study and when I wrote about it I got schooled by Keith Laws, a British critic of this work. Guild interests are always at play to some extent. How to avoid that, I do not know but I agree that open critical discussion with transparency is important.

This is my struggle. I see CBT as a tool. From psychotherapy outcome studies, the suggestion is that the particular tool does not matter so much; the treatment alliance does. It does not surprise me that some in the CBT group went on medications. These were people who were resistant to try. One outcome of an extended conversation might be to talk further about the pros and cons of drug therapy. The challenge is that our current system of care tends to put drugs front and center and when someone declines, we do not have ready tools or expectations to just start a conversation about the experience and just attempt to engage. And although some here seem to disagree, the current system of care/treatment standards promotes early use of drugs as the cornerstone to care. When a person refuses, that refusal becomes the focus of our interaction. CBT at least offers a different way to engage. Over time, with some sort of engagement, some will get better. Why not try to support them? When we were in RAISE, it was all about engagement.We had trouble getting most to the IRT clinician. How to study that?

Today on MIA there is yet another post on ISPS. Ron Unger describes a presentation by a woman and her psychiatric nurse.She was extremely symptomatic for many years and then slowly recovered fully. It certainly appears that the relationship was instrumental to this. Yes, an N of 1, but I think you value these kinds of reports.

http://www.madinamerica.com/2015/04/reflections-on-compassion-and-uncertainty/

Thanks for your revealing take on the Lancet CBT for un-medicated psychosis paper. You might be interested in the parallels with my re-analysis from last year – http://keithsneuroblog.blogspot.co.uk/2014/02/my-bloody-valentine-cbt-for-unmedicated.html?m=1

and our letter on this RCT subsequently published in the Lancet http://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lancet/PIIS014067361461271X.pdf

Regarding your question about why the ‘TAU’ get worse – one clear possibility is that that TAU is *not* TAU – as the authors say “many of these participants were discharged by their clinical teams during the trial for non-attendance or continued reluctance to accept medicine.” – so, its CT vs. people left (alone) to their own devices…hardly surprising that some get worse at some point.

What is, for me, more remarkable is how this ‘TAU’ group improved as much as the CT group during the 9 months of the trial – suggesting that the CT change may simply be within the ‘normal range of symptom change’ we might see in people not taking medication

It is also clear that many of these un-medicated individuals ended-up on medications at some point during the trial – and of those in the CT group showing symptom reduction at the end of the 9 month trial, one-third were medicated including those with the largest symptom reductions

GD: Personally, I’m not arguing for psychotherapy *alone* as a best course, but I do think that it ought to be offered to everyone.

I’m personally somewhat biased against CBT (no doubt unfairly), largely because the people I’ve met who really advocated it were just not the brightest bulbs. And I’ve had friends dealing with depression who were studying philosophy or literature as grad students who just felt like they were being asked to accept really dumb propositions with no subtlety, nuance or tolerance for ambiguity. I worked on a psych rehab demonstration project once, and the psychologist-advisor who had developed an evidence-based mental health self-management program, said that there were exactly 4 types of motivation. Really? Go read some Sophocles. And she just completely unaware of culture, reading fears of African-American clients that they were being watched as paranoia and a symptom of their shizophrenia, when, in fact, it was totally realistic that white shop keepers were going to be keeping an eye on these lower-income black people. So that’s my bias.

But my main point is that if you want to study really specific techniques in a randomized way, you might need to break down the group into smaller less heterogeneous groups. Somebody with poor caregiving experiences might find that psychotic symptoms increased when they were trying to get close to someone (something a therapist could address in psychotherapy) in a way that didn’t apply to someone without that kind of trauma.

Morrison’s trial of cognitive behavior therapy for psychosis is a seriously flawed modest study with more authors than patients remaining at the last follow-up. In exchange of letters at Lancet, we got them to admit they didn’t show that CBT was effective. Nonetheless, the authors of understanding psychosis, who overlap with the authors of the Lancet paper, continue to mislead patients and policymakers with claims that the Morrison study demonstrated CBT was as effective as antipsychotics.

See these links for my extended critique of the study.

Much ado about very little: Lancet study of cognitive therapy for persons with unmedicated schizophrenia http://blogs.plos.org/mindthebrain/2014/02/25/much-ado-little-lancet-study-cognitive-therapy-persons-unmedicated-schizophrenia/

Much ado about a modest and misrepresented study of CBT for schizophrenia: Part 2 http://blogs.plos.org/mindthebrain/2014/03/11/much-ado-modest-misrepresented-trial-cbt-schizophrenia-part-2/