NOTE: I have a Conflict of Interest about this report. It’s from the NIMH funded RAISE Study [Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode]. My conflict is that I have two interests. First, I’m really interested in this particular study on the impact of psychosocial treatment on these First Episode Patients. But second, I’m exhausted with academic researchers with extensive industry connections – suspicious of almost everything they publish. John Kane is such a person. Here are a few comments about his extensive industry connections – prelapse: but there’s more…. I was particularly put off by his comments about COI in an interview here. He is the Principle Investigator for this NIMH RAISE study…

|

In spite of the persistent divisive rhetoric, there seems to be a developing consensus about the treatment of psychotic mental illness [schizophrenia]. The notion that the only treatment is antipsychotic medication "for life" has been laid to rest [largely through the efforts of Robert Whitaker and his colleagues at Mad in America]. Most agree that the medication is indicated for acute psychosis, but controversy persists about maintenance [in general, independent of the advice given, the patients themselves don’t continue to take it long term]. There’s a developing consensus that ongoing care for these patients from a mental health system or provider is essential, over and beyond the issue of medication. The form of that ongoing care is unclear, and the subject of heated debate. Most hope for some way to identify these patients before a psychotic break [but worry that it will lead to overmedication]. There is a concern, mainly in the lay population, that these patients are dangerous. Likewise, there is a concern almost everywhere that chronic psychotic patients are inappropriately housed in jails and prisons. With that as an introduction, yesterday we read this in the New York Times:

New York Times

by BENEDICT CAREY

OCT. 20, 2015

More than two million people in the United States have a diagnosis of schizophrenia, and the treatment for most of them mainly involves strong doses of antipsychotic drugs that blunt hallucinations and delusions but can come with unbearable side effects, like severe weight gain or debilitating tremors.

Now, results of a landmark government-funded study call that approach into question. The findings, from by far the most rigorous trial to date conducted in the United States, concluded that schizophrenia patients who received smaller doses of antipsychotic medication and a bigger emphasis on one-on-one talk therapy and family support made greater strides in recovery over the first two years of treatment than patients who got the usual drug-focused care.

The report, to be published on Tuesday in The American Journal of Psychiatry and funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, comes as Congress debates mental health reform and as interest in the effectiveness of treatments grows amid a debate over the possible role of mental illness in mass shootings…

So we’ll likely agree with his conclusion. The problem is that he’s talking about the NIMH Study RAISE-ETP [Recovery After Initial Schizophrenic Episode] and the results published in the American Journal of Psychiatry yesterday ahead of print:

2-Year Outcomes From the NIMH RAISE Early Treatment Program

by John M. Kane, M.D., Delbert G. Robinson, M.D., Nina R. Schooler, Ph.D., Kim T. Mueser, Ph.D., David L. Penn, Ph.D., Robert A. Rosenheck, M.D., Jean Addington, Ph.D., Mary F. Brunette, M.D., Christoph U. Correll, M.D., Sue E. Estroff, Ph.D., Patricia Marcy, B.S.N., James Robinson, M.Ed., Piper S. Meyer-Kalos, Ph.D., L.P., Jennifer D. Gottlieb, Ph.D., Shirley M. Glynn, Ph.D., David W. Lynde, M.S.W., Ronny Pipes, M.A., L.P.C.-S., Benji T. Kurian, M.D., M.P.H., Alexander L. Miller, M.D., Susan T. Azrin, Ph.D., Amy B. Goldstein, Ph.D., Joanne B. Severe, M.S., Haiqun Lin, M.D., Ph.D., Kyaw J. Sint, M.P.H., Majnu John, Ph.D., and Robert K. Heinssen, Ph.D., A.B.P.P.

American Journal of Psychiatry. Published on-line Oct 20, 2015.

Objective: The primary aim of this study was to compare the impact of NAVIGATE, a comprehensive, multidisciplinary, team-based treatment approach for first-episode psychosis designed for implementation in the U.S. health care system, with community care on quality of life.

Method: Thirty-four clinics in 21 states were randomly assigned to NAVIGATE or community care. Diagnosis, duration of untreated psychosis, and clinical outcomes were assessed via live, two-way video by remote, centralized raters masked to study design and treatment. Participants [mean age, 23] with schizophrenia and related disorders and ≤6 months of antipsychotic treatment [N=404] were enrolled and followed for ≥2 years. The primary outcome was the total score of the Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale, a measure that includes sense of purpose, motivation, emotional and social interactions, role functioning, and engagement in regular activities.

Results: The 223 recipients of NAVIGATE remained in treatment longer, experienced greater improvement in quality of life and psychopathology, and experienced greater involvement in work and school compared with 181 participants in community care. The median duration of untreated psychosis was 74 weeks. NAVIGATE participants with duration of untreated psychosis of <74 weeks had greater improvement in quality of life and psychopathology compared with those with longer duration of untreated psychosis and those in community care. Rates of hospitalization were relatively low compared with other first-episode psychosis clinical trials and did not differ between groups.

Conclusions: Comprehensive care for first-episode psychosis can be implemented in U.S. community clinics and improves functional and clinical outcomes. Effects are more pronounced for those with shorter duration of untreated psychosis.

And here’s the description of the study published earlier this year:

background, rationale, and study design.

by Kane JM, Schooler NR, Marcy P, Correll CU, Brunette MF, Mueser KT, Rosenheck RA, Addington J, Estroff SE, Robinson J, Penn DL, and Robinson DG.

Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2015 76[3]:240-246.

OBJECTIVE: The premise of the National Institute of Mental Health Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode Early Treatment Program [RAISE-ETP] is to combine state-of-the-art pharmacologic and psychosocial treatments delivered by a well-trained, multidisciplinary team in order to significantly improve the functional outcome and quality of life for first-episode psychosis patients. The study is being conducted in non-academic [ie, real-world] treatment settings, using primarily extant reimbursement mechanisms…

I first got interested in the RAISE study after reading a blog post by Dr. Insel that didn’t sound right to me [

Director’s Blog: From Research to Practice]. It was written up as an example of translation – research to practice. It seems like it was not that:

But in looking, I got interested in the RAISE study for itself. The design was to compare treatment-as-usual and a particular structured approach [

NAVIGATE] to First Episode of Psychosis patients delivered in existing non-academic community settings ["

naturalistic"]. One component was

COMPASS, a medication algorithm designed for this study [I couldn’t find out anything about it]. Another component is

IRT [

Individualized Resiliency Training] that comes with a

Manual. Here are my musings about that

IRT Manual:

In summary, there were two RAISE studies. Dr. Lieberman’s version floundered for recruitment issues, and was retroactively spun away as a pilot and disappeared. About that Manual – I was disappointed. It was something of a "coping skills" outing [and it actually suggested things like "chemical imbalance" etc. used to encourage subjects to stay on their meds]. When the opportunity for block grant money from SAMHSA appeared for community treatment appeared, the materials from RAISE were quickly assembled to take advantage of the opportunity – even though RAISE wasn’t yet completed. That was Insel’s Translational moment – more opportunistic than Translational.

So why the long introduction? It’s because when I looked at Dr. Kane et al’s paper, I could find little relationship to the AJP paper and Benedict Carey’s New York Times article [or for that matter, any of the other media reports]. Carey had reported lower antipsychotic doses, but the paper says nothing about medications. Cary’s article mentioned one-to-one talk therapy but I found not much about that in this report. What I did find first off were graphs of the answers to quality assurance questionnaires:

And then there was this showing some modest improvements in the NAVIGATE group [though the metrics seem odd and fairly distant from the data – statistical testing of only the treatment×time interaction???]:

There was a companion AJP piece by Dr. Insel [RAISE-ing Our Expectations for First-Episode Psychosis]. He said:

This issue of the Journal includes a report on the primary outcomes from the Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode [RAISE] Early Treatment Program clinical trial. …RAISE was not a test of a breakthrough intervention or high-tech diagnostic but a trial of adapting and optimizing currently known, evidence-based practices. The RAISE question was simple and urgent: Will a comprehensive, person-centered, team-based approach for first-episode psychosis improve outcomes? For RAISE, the outcomes measured were quality of life, participation in school or work, and symptomatic improvement. The setting was “ real world ”— 34 community mental health centers in 21 states.

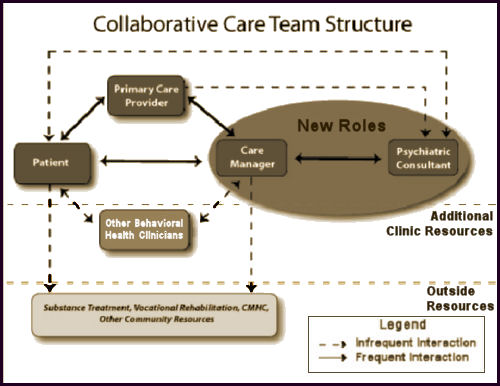

This issue of the The study compared the efficacy of an experimental intervention, called NAVIGATE, with standard community care for people with first-episode psychosis. NAVIGATE consisted of four evidence-based interventions: personalized medication management, family psychoeducation, resilience-focused individual therapy, and supported employment and education. The component interventions were offered as a package, with the addition of a team leader who coordinated services and served as a primary point of contact for individuals and their families. The NAVIGATE programs also involved a proactive focus on engagement. In contrast to standard community care, these multiple components were offered within a shared decision-making framework and implemented according to patient preference.

Just as the dramatic improvements for treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia reflected incremental gains over time, the results for NAVIGATE take a palpable step toward markedly better outcomes for young people following first-episode psychosis. A measure of quality of life improved modestly more in the NAVIGATE group than in the standard community care group over 24 months [effect size = 0.31], and the NAVIGATE group had lower levels of symptoms as measured by the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale [effect size = 0.29]. Participants in the NAVIGATE group stayed in treatment longer than the standard community care group [a median of 23 months compared with a median of 17 months]. In contrast to some earlier studies of first- episode psychosis , the intervention did not decrease hospitalization probably because the rates of hospitalization were relatively low in both groups [over the 2 years of treatment, 34% of the NAVIGATE group and 37% of the standard community care group were hospitalized for psychiatric indications].

One of the most remarkable aspects of this study was the substantial moderation of the treatment effect by the duration of untreated psychosis. The median duration of untreated psychosis in the entire sample was 74 weeks — a clear indication of the need to identify young people with mental illness at much earlier stages and to get them into effective treatment more rapidly. Those with a duration of untreated psychosis of less than the median of 74 weeks responded far better to the NAVIGATE intervention than those with a longer duration of untreated psychosis at baseline. Indeed, the overall effects of NAVIGATE were largely driven by the robust response [the effect size was 0.54 for the quality of life measure and was 0.42 for overall symptoms] from those with shorter duration of untreated psychosis. These results demonstrate the importance of early detection, early engagement, and integrated care following the onset of psychosis…

Seems like if the medication doses were lower, Dr. Insel would’ve noticed and commented. Then I started finding commentary like this:

VICE NEWS

By Colleen Curry

Oct 21, 2015

A landmark study into the treatment of newly diagnosed schizophrenics has found that talk therapy combined with medication can be more effective in treating symptoms than just strong doses of drugs. The findings, which emphasize the success of therapy and how unusual it is for schizophrenics to be treated with it, could help shift the way health insurers in the United States cover mental health treatment costs.

Researchers spent four years studying more than 200 newly diagnosed schizophrenics. Half of the subjects were treated solely with medication, while the other half received a lower-dose medication combined with individual therapy, coaching sessions in the workplace or school, and family counseling.

The study involved patients at 34 treatment centers in 21 states. The results, released Tuesday in the American Journal of Psychiatry, found that individuals in the early stages of schizophrenia were better off receiving lower-doses of antipsychotics in conjunction with therapy. The National Alliance of Mental Illness (NAMI) praised the study and said it would be used as part of the organization’s push to broaden access to services for the mentally ill…

The study’s release coincided with hearings on Capitol Hill for mental reform amid a bipartisan push to improve mental health treatment, partially due to the increase in mass shootings in which mental illness is thought to have played a role.

This article, while still in the upbeat mode, was the most rational of the bunch:

Washington Post

By Lenny Bernstein

October 20, 2015

Quickly identifying people who have suffered a first schizophrenic episode and treating them with coordinated, sustained services sharply boosts their chances of leading productive lives, according to a major study being published Tuesday. And the treatment can be provided in a typical community mental health setting, the researchers concluded…

The study, called Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode (RAISE), found that people who are provided years of “coordinated specialty care” in community clinics had a greater quality of life, more involvement in work and school, and less ongoing pathology than others who received typical care.

Although this approach is more expensive and labor-intensive, the researchers suggest that it may be cost-effective in the long run. The approach includes psychotherapy, medication, supported employment and education, help for families of the mentally ill person, and case management. Much of the effort can be funded under insurance and government reimbursement policies, the researchers note.

The study confirms previous research results that the most critical element of treatment may be starting it as quickly as possible after a first psychotic episode. It found “a substantial difference” in effect for patients who began treatment less than 74 weeks after their first symptoms — the median length of time that people in the study went untreated after the onset of psychosis.

“Doing the right thing — and doing the right thing at the right time — that’s the key finding,” said Robert Heinssen, director of the division of services and intervention research at the National Institute of Mental Health, which funded the $25 million, six-year study. “That is guiding our efforts going forward. That has become the north star of where we’re going”…

Cost remains a challenge, because some of the services offered by the comprehensive care model are not reimbursed under traditional fee-for-service arrangements, Kane and his colleagues said. Last week, though, three federal agencies issued guidance to help states design benefit packages for treatment of first-episode psychosis using Medicaid and mental health block-grant funds.

I’ve spent the better part of the last two days chasing down leads about the

RAISE Study, including writing some people who were involved with it. The paper itself and the hype about it in the media feel out of sync to me. That’s complicated by the fact that my own bias is on the side of the media version.

Dinah at

ShrinkRap says the same thing I felt on first reading it:

In sum: Patients with schizophrenia do better if they get comprehensive services, and they do better if they are treated early in the course of their illness. And now we officially know what we all knew.

But after reading and reading, I’m afraid my reaction is a bit more critical than that. I suspect that the published paper casts the study is the best possible light [or better], and that the untouched data is less glowing. The NIMH track record with naturalistic studies isn’t so hot [as in STAR*D]. And from what I’ve highlighted above, it’s obvious that this paper in linked to a campaign for more mental health funding [which is more than fine by me]. So to the dilemma. I support the conclusions and their implications, but am suspicious that a closer look at RAISE would raise lots of questions. Like I said at the outset…

|

NOTE: I have a Conflict of Interest about this report….

|

see also:

Mad in America

by by Justin Karter

October 21, 2015

NIMH: Director’s Blog

by By Thomas Insel

October 20, 2015

NIH: Director’s Blog

by Dr. Francis Collins

October 20, 2015

Thanks to a compounding pharmacy, Martin Shkreli’s company may no longer have a lock on the market for its pricey anti-infective drug Daraprim. A little-known company called Imprimis Pharmaceuticals announced plans to make a combination medicine that includes pyrimethamine, the same active ingredient found in Daraprim. And Imprimis

Thanks to a compounding pharmacy, Martin Shkreli’s company may no longer have a lock on the market for its pricey anti-infective drug Daraprim. A little-known company called Imprimis Pharmaceuticals announced plans to make a combination medicine that includes pyrimethamine, the same active ingredient found in Daraprim. And Imprimis

I was looking at my old patent-life graph I used in

I was looking at my old patent-life graph I used in  But even without the pressure from PHARMA and an empty pipeline, these drugs are selling like hot-cakes, and the consensus is that they are still way over-prescribed [at least my consensus]. With the increasingly large databases from healthcare plans and the government, we ought to be able to figure out why. And we need to know how many stay on the drugs just to avoid withdrawal symptoms, and figure out how to help them safely get off. Many of the problem come with long term use, and a lot of patients and doctors continue them as "preventive insurance" or something like that in inproven situations. Also, it appears that the generic drug makers are jumping on the high price band-wagon along with the patent-holders, so somebody needs to curb that trend. And I suspect that PHARMA isn’t the only industry pushing these medications. Managed Care and other third party payers like the drugs because in spite of their high cost, they are still cheaper than other interventions and they get a checkmark in the treatment box [an analogy to deinstitutionalization comes to mind].

But even without the pressure from PHARMA and an empty pipeline, these drugs are selling like hot-cakes, and the consensus is that they are still way over-prescribed [at least my consensus]. With the increasingly large databases from healthcare plans and the government, we ought to be able to figure out why. And we need to know how many stay on the drugs just to avoid withdrawal symptoms, and figure out how to help them safely get off. Many of the problem come with long term use, and a lot of patients and doctors continue them as "preventive insurance" or something like that in inproven situations. Also, it appears that the generic drug makers are jumping on the high price band-wagon along with the patent-holders, so somebody needs to curb that trend. And I suspect that PHARMA isn’t the only industry pushing these medications. Managed Care and other third party payers like the drugs because in spite of their high cost, they are still cheaper than other interventions and they get a checkmark in the treatment box [an analogy to deinstitutionalization comes to mind].