Posted on Friday 18 September 2015

PLoS Medicineby Yasmina Molero, Paul Lichtenstein, Johan Zetterqvist, Clara Hellner Gumpert, and Seena FazelSeptember 15, 2015

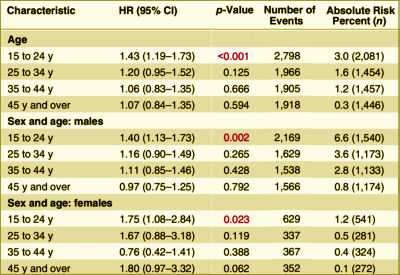

Background: Although selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs] are widely prescribed, associations with violence are uncertain.Methods and Findings: From Swedish national registers we extracted information on 856,493 individuals who were prescribed SSRIs, and subsequent violent crimes during 2006 through 2009. We used stratified Cox regression analyses to compare the rate of violent crime while individuals were prescribed these medications with the rate in the same individuals while not receiving medication. Adjustments were made for other psychotropic medications. Information on all medications was extracted from the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register, with complete national data on all dispensed medications. Information on violent crime convictions was extracted from the Swedish national crime register. Using within-individual models, there was an overall association between SSRIs and violent crime convictions [hazard ratio [HR] = 1.19, 95% CI 1.08–1.32, p < 0.001, absolute risk = 1.0%]. With age stratification, there was a significant association between SSRIs and violent crime convictions for individuals aged 15 to 24 y [HR = 1.43, 95% CI 1.19–1.73, p < 0.001, absolute risk = 3.0%]. However, there were no significant associations in those aged 25–34 y [HR = 1.20, 95% CI 0.95–1.52, p = 0.125, absolute risk = 1.6%], in those aged 35–44 y [HR = 1.06, 95% CI 0.83–1.35, p = 0.666, absolute risk = 1.2%], or in those aged 45 y or older [HR = 1.07, 95% CI 0.84–1.35, p = 0.594, absolute risk = 0.3%]. Associations in those aged 15 to 24 y were also found for violent crime arrests with preliminary investigations [HR = 1.28, 95% CI 1.16–1.41, p < 0.001], non-violent crime convictions [HR = 1.22, 95% CI 1.10–1.34, p < 0.001], non-violent crime arrests [HR = 1.13, 95% CI 1.07–1.20, p < 0.001], non-fatal injuries from accidents [HR = 1.29, 95% CI 1.22–1.36, p < 0.001], and emergency inpatient or outpatient treatment for alcohol intoxication or misuse [HR = 1.98, 95% CI 1.76–2.21, p < 0.001]. With age and sex stratification, there was a significant association between SSRIs and violent crime convictions for males aged 15 to 24 y [HR = 1.40, 95% CI 1.13–1.73, p = 0.002] and females aged 15 to 24 y [HR = 1.75, 95% CI 1.08–2.84, p = 0.023]. However, there were no significant associations in those aged 25 y or older. One important limitation is that we were unable to fully account for time-varying factors.Conclusions: The association between SSRIs and violent crime convictions and violent crime arrests varied by age group. The increased risk we found in young people needs validation in other studies.

[cropped to fit the space]

Besides having access a cohort of 8+M people [~10% on SSRIs] with their prescription records and the public records of every brush with the law, they had some mighty fine computers and statisticians to have extracted their data and cross-checked so many covariates. I couldn’t possibly"vet" all of their analyses. But the core thread is that they isolated periods when patients were "on" SSRIs and when they were "off" the medication, and they compared the arrest rates for violent crimes "on" and "off" – deriving a Hazard Ratio.

-

Gibbons RD, Hur K, Bhaumik DK, Mann JJ.Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005 Feb;62(2):165-72.

-

Gibbons RD, Hur K, Bhaumik DK, Mann JJ.Am J Psychiatry. 2006 Nov;163(11):1898-904.

-

Charles B. Nemeroff, Amir Kalali, Martin B. Keller, Dennis S. Charney, Susan E. Lenderts, Elisa F. Cascade, Hugo Stephenson, and Alan F. SchatzbergArch Gen Psychiatry. 2007 Apr;64(4):466-472.

-

Nakagawa A, Grunebaum MF, Ellis SP, Oquendo MA, Kashima H, Gibbons RD, Mann JJ.J Clin Psychiatry. 2007 Jun;68(6):908-916.

-

Benji T. Kurian, MD, MPH; Wayne A. Ray, PhD; Patrick G. Arbogast, PhD; D. Catherine Fuchs, MD; Judith A. Dudley, BS; William O. Cooper, MD, MPHJAMA: Pediatrics. 2007 Jun;161(7):690-696.

-

Gibbons RD, Brown CH, Hur K, Marcus SM, Bhaumik DK, Mann JJ.Am J Psychiatry. 2007 Jul;164(7):1044-1049.

-

Early evidence on the effects of regulators’ suicidality warnings on SSRI prescriptions and suicide in children and adolescents. [see peaks and valleys…]Gibbons RD, Brown CH, Hur K, Marcus SM, Bhaumik DK, Erkens JA, Herings RM, Mann JJ.Am J Psychiatry. 2007 Sep;164(9):1356-1363.

-

Brown CH, Wyman PA, Brinales JM, Gibbons RD.Int Rev Psychiatry. 2007 Dec;19(6):617-631.

-

Gibbons RD, Segawa E, Karabatsos G, Amatya AK, Bhaumik DK, Brown CH, Kapur K, Marcus SM, Hur K, Mann JJ.Stat Med. 2008 May 20;27(11):1814-1833.

-

Barry CL and Busch SH.Pediatrics. 2010 125[1]:88-95.

-

Gibbons RD, Mann JJ.Drug Saf. 2011 May 1;34(5):375-395.

-

Susan Busch, Ezra Golberstein, Ellen MearaNATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH, September 2011.

-

Robert D. Gibbons, Hendricks Brown, Kwan Hur, John M. Davis, and J. John MannArch Gen Psychiatry. 2012 Jun;69(6):580-587.

-

Gibbons RD, Coca Perraillon M, Hur K, Conti RM, Valuck RJ, and Brent DAPharmacoepidemiologic Drug Safety. 2014 Sep 29. doi: 10.1002/pds.3713. [Epub ahead of print]

-

Christine Y Lu, Fang Zhang , Matthew D Lakoma analyst, Jeanne M Madden, Donna Rusinak, Robert B Penfold, Gregory Simon, Brian K Ahmedani, Gregory Clarke, Enid M Hunkeler, Beth Waitzfelder, Ashli Owen-Smith, Marsha A Raebel, Rebecca Rossom, Karen J Coleman, Laurel A Copeland, Stephen B SoumeraiBMJ. 2014 348:g3596.

-

PSYCHIATRICNEWSby Mark Moran12/30/2014

-

by Richard A. Friedman, M.D.New England Journal of Medicine 2014 371:1666-1668.

-

by Marc B. Stone, M.D.New England Journal of Medicine 2014 371:1668-1671.

-

New York Timesby Richard A. FriedmanAUGUST 3, 2015