The goals of Integrated Care: Working at the Interface of Primary Care and Behavioral Health are to educate psychiatrists about the fundamental shift underway in health care and to prepare them to be successful and effective in the new health care arena. The passage and implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act presents an opportunity for newly insured patients and for funding models of integrated care, enabling psychiatrists to have a more significant population-level impact…

Edited by Lori E. Raney, M.D.

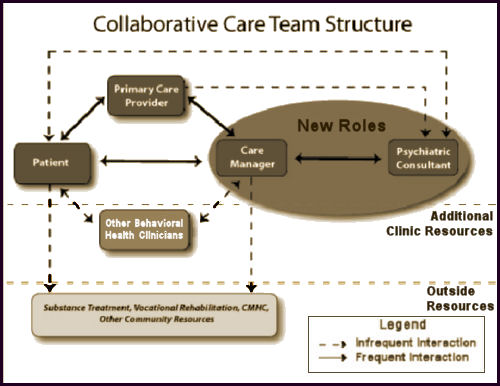

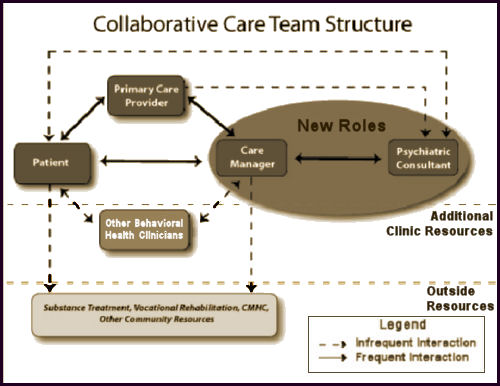

The integration of physical and mental health care is an important aspect of the Medicaid health home model. Collaborative care programs are one approach to integration in which primary care providers, care managers, and psychiatric consultants work together to provide care and monitor patients’ progress. These programs have been shown to be both clinically-effective and cost-effective for a variety of mental health conditions, in a variety of settings, using several different payment mechanisms. This brief highlights the collaborative care model as one approach to implementing integrated care under the Medicaid health homes authority.

"

… developing innovative integrated care models and translating research on evidence-based behavioral health interventions into effective clinical and public health practice." I admit to an involuntary visceral aversion to this kind of jargon filled patter. And it seems to be the preferred rhetoric in a lot of the literature on Collaborative Care [AKA Integrative Care] that apparently looms as a vision of the future for psychiatry [

two versions…,

my say…,

not directly seeing the patients…]. It’s obviously a big push item from

SAMHSA,

APA,

Medicare,

Medicaid,

ACA,

Managed Care, etc. This, from one of the epicenters at the

University of Washington:

Collaborative Care is a specific type of integrated care developed at the University of Washington that treats common mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety that require systematic follow-up due to their persistent nature. Based on principles of effective chronic illness care, Collaborative Care focuses on defined patient populations tracked in a registry, measurement-based practice and treatment to target. Trained primary care providers and embedded behavioral health professionals provide evidence-based medication or psychosocial treatments, supported by regular psychiatric case consultation and treatment adjustment for patients who are not improving as expected.

Collaborative Care originated in a research culture and has now been tested in more than 80 randomized controlled trials in the US and abroad. Several recent

meta-analyses make it clear that Collaborative Care consistently improves on care as usual. It leads to better patient outcomes, better patient and provider satisfaction, improved functioning, and reductions in health care costs, achieving the Triple Aim of health care reform. Collaborative Care necessitates a practice change on multiple levels and is nothing short of a new way to practice medicine, but it works. The bottom line is that patients get better.

[click image for description]

Obviously, from all the noise from the APA higher-ups and PsychiatricNews, the APA had its hand in this story. Essentially, it’s a step beyond the last sell out in that psychiatrists have a sit down with the Care Manager and discuss cases of patients they’ve never seen, making suggestions to be passed on to others. The only reason that the psychiatrist is there is that they’ve figured out that the primary care docs know nothing of mental illness and prescribe very badly. So we’re there to prescribe better – only to do it blindfolded – formerly known as malpractice. It’s an absurd scheme that can only produce psychiatrists that end up as in the dark as the primary care doctors they advise via proxy. So it’s at least clear why the rhetoric is so jargon filled – take away the jargon and there’s nothing there. My advice? Insert No Roles where it says New Roles.

The great irony of this legacy passed on to us from the PHARMA tarnished KOLs who sold out psychiatry long ago is that it forces anyone participating in it to do the very thing that everyone is complaining about – see medication as the first line treatment of mental illness and overprescribe. To even amplify the irony, this model is essentially supported and encouraged by the people who criticize the bio-bio-bio models the most [see the rise and ??? of the guild…]. The KOLs and PHARMAs of the decades bracketing the century mark succeeded in reducing psychiatry to pill-pushing for their profit and this is what they’ve passed along to us – now encoded as Collaborative Care. What other Behavioral Health Clinicians haven’t quite figured out is that they are on a dotted line too, and are already feeling their future dwindling along with psychiatry and headed for a similar fate. Unfortunately, for all concerned, all of this actually hinges on the business-fication of the word "Care," and is unlikely to change until society rediscovers other meanings of the word. Like the bumper sticker in the 1980s prophetically said, "Managed Care is Neither!"

Here are the abstracts of the reliable meta-analyses so far:

The Cochrane Collaboration

by Janine Archer, Peter Bower, Simon Gilbody, Karina Lovell, David Richards, Linda Gask, Chris Dickens, and Peter Coventry

17 OCT 2012

Background: Common mental health problems, such as depression and anxiety, are estimated to affect up to 15% of the UK population at any one time, and health care systems worldwide need to implement interventions to reduce the impact and burden of these conditions. Collaborative care is a complex intervention based on chronic disease management models that may be effective in the management of these common mental health problems.

Objectives: To assess the effectiveness of collaborative care for patients with depression or anxiety.

Search methods: We searched the following databases to February 2012: The Cochrane Collaboration Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group [CCDAN] trials registers [CCDANCTR-References and CCDANCTR-Studies] which include relevant randomised controlled trials [RCTs] from MEDLINE [1950 to present], EMBASE [1974 to present], PsycINFO [1967 to present] and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials [CENTRAL, all years]; the World Health Organization [WHO] trials portal [ICTRP]; ClinicalTrials.gov; and CINAHL [to November 2010 only]. We screened the reference lists of reports of all included studies and published systematic reviews for reports of additional studies. Selection criteria: Randomised controlled trials [RCTs] of collaborative care for participants of all ages with depression or anxiety.

Data collection and analysis: Two independent researchers extracted data using a standardised data extraction sheet. Two independent researchers made ‘Risk of bias’ assessments using criteria from The Cochrane Collaboration. We combined continuous measures of outcome using standardised mean differences [SMDs] with 95% confidence intervals [CIs]. We combined dichotomous measures using risk ratios [RRs] with 95% CIs. Sensitivity analyses tested the robustness of the results.

Main results: We included seventy-nine RCTs [including 90 relevant comparisons] involving 24,308 participants in the review. Studies varied in terms of risk of bias. The results of primary analyses demonstrated significantly greater improvement in depression outcomes for adults with depression treated with the collaborative care model in the short-term [SMD -0.34, 95% CI -0.41 to -0.27; RR 1.32, 95% CI 1.22 to 1.43], medium-term [SMD -0.28, 95% CI -0.41 to -0.15; RR 1.31, 95% CI 1.17 to 1.48], and long-term [SMD -0.35, 95% CI -0.46 to -0.24; RR 1.29, 95% CI 1.18 to 1.41]. However, these significant benefits were not demonstrated into the very long-term [RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.27]. The results also demonstrated significantly greater improvement in anxiety outcomes for adults with anxiety treated with the collaborative care model in the short-term [SMD -0.30, 95% CI -0.44 to -0.17; RR 1.50, 95% CI 1.21 to 1.87], medium-term [SMD -0.33, 95% CI -0.47 to -0.19; RR 1.41, 95% CI 1.18 to 1.69], and long-term [SMD -0.20, 95% CI -0.34 to -0.06; RR 1.26, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.42]. No comparisons examined the effects of the intervention on anxiety outcomes in the very long-term. There was evidence of benefit in secondary outcomes including medication use, mental health quality of life, and patient satisfaction, although there was less evidence of benefit in physical quality of life.

Authors’ conclusions: Collaborative care is associated with significant improvement in depression and anxiety outcomes compared with usual care, and represents a useful addition to clinical pathways for adult patients with depression and anxiety.

The Cochrane Collaboration.

by Siobhan Reilly, Claire Planner, Linda Gask, Mark Hann, Sarah Knowles, Benjamin Druss, and Helen Lester

4 NOV 2013

Background: Collaborative care for severe mental illness [SMI] is a community-based intervention, which typically consists of a number of components. The intervention aims to improve the physical and/or mental health care of individuals with SMI.

Objectives: To assess the effectiveness of collaborative care approaches in comparison with standard care for people with SMI who are living in the community. The primary outcome of interest was psychiatric admissions.

Search methods: We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Specialised register in April 2011. The register is compiled from systematic searches of major databases, handsearches of relevant journals and conference proceedings. We also contacted 51 experts in the field of SMI and collaborative care.

Selection criteria: Randomised controlled trials [RCTs] described as collaborative care by the trialists comparing any form of collaborative care with ‘standard care’ for adults [18+ years] living in the community with a diagnosis of SMI, defined as schizophrenia or other types of schizophrenia-like psychosis [e.g. schizophreniform and schizoaffective disorders], bipolar affective disorder or other types of psychosis.

Data collection and analysis: Two review authors worked independently to extract and quality assess data. For dichotomous data, we calculated the risk ratio [RR] with 95% confidence intervals [CIs] and we calculated mean differences [MD] with 95% CIs for continuous data. Risk of bias was assessed.

Main results: We included one RCT [306 participants; US veterans with bipolar disorder I or II] in this review. We did not find any trials meeting our inclusion criteria that included people with schizophrenia. The trial provided data for one comparison: collaborative care versus standard care. All results are ‘low or very low quality evidence’.Data indicated that collaborative care reduced psychiatric admissions at year two in comparison to standard care [n = 306, 1 RCT, RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.99].The sensitivity analysis showed that the proportion of participants psychiatrically hospitalised was lower in the intervention group than the standard care group in year three: 28% compared to 38% [n = 330, 1 RCT, RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.99].In comparison to the standard care group, collaborative care significantly improved the Mental Health Component [MHC] of quality of life at the three-year follow-up, [n = 306, 1 RCT, MD 3.50, 95% CI 1.80 to 5.20]. The Physical Health Component [PHC] of the quality of life measure at the three-year follow-up did not differ significantly between groups [n = 306, 1 RCT, MD 0.50, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.91].Direct intervention [all-treatment] costs of collaborative care at the three-year follow-up did not differ significantly from standard care [n = 306, 1 RCT, MD -$2981.00, 95% CI $16934.93 to $10972.93]. The proportion of participants leaving the study early did not differ significantly between groups [n = 306, 1 RCT, RR 1.71, 95% CI 0.77 to 3.79]. There is no trial-based information regarding the effect of collaborative care for people with schizophrenia.No statistically significant differences were found between groups for number of deaths by suicide at three years [n = 330, 1 RCT, RR 0.34, 95% CI 0.01 to 8.32], or the number of participants that died from all other causes at three years [n = 330, 1 RCT, RR 1.54, 95% CI 0.65 to 3.66].

Authors’ conclusions: The review did not identify any studies relevant to care of people with schizophrenia and hence there is no evidence available to determine if collaborative care is effective for people suffering from schizophrenia or schizophreniform disorders. There was however one trial at high risk of bias that suggests that collaborative care for US veterans with bipolar disorder may reduce psychiatric admissions at two years and improves quality of life [mental health component] at three years, however, on its own it is not sufficient for us to make any recommendations regarding its effectiveness. More large, well designed, conducted and reported trials are required before any clinical or policy making decisions can be made.

This is a population model that incorporates various instruments [screening, PHQ-9, etc] along the way. It’s built on the naive notion that one can treat mental health problems with a prescription pad and/or CBT. It reminds me of a graphic I drew when I first started blogging about psychiatry and mental health matters a number of years ago. I drew it meaning to be facetious, but maybe I should have applied for a patent…

This is a population model that incorporates various instruments [screening, PHQ-9, etc] along the way. It’s built on the naive notion that one can treat mental health problems with a prescription pad and/or CBT. It reminds me of a graphic I drew when I first started blogging about psychiatry and mental health matters a number of years ago. I drew it meaning to be facetious, but maybe I should have applied for a patent…

The graph is the number of companies he was a paid to advise by year. Note what happened when Dr. Grassley investigated him – and the ones left were in the minor leagues. If it were his expertise that mattered, it would’ve been a different story. Certainly there have been genuine experts who worked for/with industry as documented in Rosenbaum’s articles, but they were exceptions to the rule [and we all know that]. The usual hire is for a ticket into the literature.

The graph is the number of companies he was a paid to advise by year. Note what happened when Dr. Grassley investigated him – and the ones left were in the minor leagues. If it were his expertise that mattered, it would’ve been a different story. Certainly there have been genuine experts who worked for/with industry as documented in Rosenbaum’s articles, but they were exceptions to the rule [and we all know that]. The usual hire is for a ticket into the literature.