Posted on Monday 13 October 2014

Raleigh NC

As mentioned in the prequel…, the 2014 landscape in psychiatry is very different from the year 1980 or even the year 2000. Exposures of scientific and commercial misconduct swept through academic psychiatry and the pharmaceutical industry; the psychopharmacology pipeline ran dry; PHARMA took "a runner" from CNS drug development altogether taking its liberal support of academic institutions and the APA with it; the DSM-5 Revision floundered in something of a public spectacle; and there was a growing backlash against the monocular biomedical directions in psychiatry in general and the efficacy and safety of the widely used medications in specific. Most psychotherapy had been handed off to other disciplines in the 1980s. These days, most medication is being prescribed by Primary Care Physicians. Most Psychiatric hospitals are closed. Many chronically mentally ill patients are in jail, prisons, or shelters. And the ACA [Affordable Care Act] looks to turn the third party system further upside down. After a frantic year or so trying to woo PHARMA back without success, the place and fate of psychiatry are again in question – endangered species? obsolete? severe shortages? train more? train less? train none? are the kind of phrases being thrown around [or hurled].

Most practicing psychiatrists have grown up in the post-1980 era – by which I mean that within the body of the APA, there’s little apparent turmoil or faction. If there’s much of a call for change or reform coming from inside the ranks, I don’t know about it. Incidentally, there are many psychiatrists who are off the grid for a multiplicity of reasons, suggesting that there’s not much room for discord, controversy, or dialog within the APA. And so to the subject: the APA’s continued assumption that it is tasked with defining, rather than representing, the body psychiatric – persistent since the the days of Sabshin and Spitzer.

In unanswered questions…, I was mentioning several articles in the PsyciatricNews where Presidents of the APA are talking about the future of psychiatry being in Integrative Care, Collaborative Care, and Population Health. I added another in which the APA is offering a course on Recovery [with a capital R] meaning Recovery as it is formulated by SAMHSA [Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Agency] or as you might read about it on many websites opposed to the current medication-heavy brief-contact psychiatric practices. That is a huge topic that I’m not going to talk about substantively in this post, not because I don’t have something to say or don’t want to say it, but for the opposite reason. It’s too big for a simple blog post [and there are too many distracting rants along the way]. Right now I want to talk about just one simple thing. There is a growing trend in what’s coming from the upper levels of the APA that the redirection of psychiatry and the redefinition of psychiatrists is what the organization is setting out to do – what it’s supposed to be doing.

That’s a bad habit that needs a great deal of reflection, because that’s what the APA did in 1980 – created a psychiatry that fit the prevailing vision of what physicians should do in the face of Managed Care’s insistence – see sick people, make a diagnosis, give them the treatment for their sickness, then send them on their way. So the APA created a dictionary to catalog those diseases in concrete terms, and industry went about coming up with a compendium of treatments keyed to the catalog. There are some mental diseases that can be classified in that way, and some treatments that can be used in that way. But being the only model in town, it inappropriately generalized to be the model for all comers. Then the medication makers jumped on board, engaged with psychiatry, and made an ill-gained fortune. We now live in a world where the system that the APA actively created, encouraged, and maintained is currently a very big problem – and psychiatrists are villified for going along with it.

And now the APA is making noises about another major redefinition as we move into the future, and appears to be pitching it to its membership. While there’s much to be said about what’s being pitched [next post], there’s a question that comes before that. Should the APA even be on the pitching mound at this point. The suggested changes aren’t coming from the floor of the membership. They’re not coming from some subgroup of psychiatrists intensely studying a problem, nor a subgroup of practitioners who have long-occupied the suggested roles, nor the halls of physical medicine, nor being introduced as a topic for general debate within psychiatry itself. My premise is obvious, that the centrality of the APA upper echelon in defining psychiatry has been maintained and used to keep psychiatry on a path controlled by industrial and ideological forces – a legacy from Sabshin, Spitzer, and 1980s DSM-III – whether that was their intent or not and it’s being exerted once again.

Now, the APA is pushing a major change in the directions of the profession in the face of the exhaustion of the current paradigm that will have not only an effect on practice and third party reimbursement, it does nothing to deal with the plight of the chronic patients now incarcerated; it does nothing to curb overuse of psychiatric medications particularly by primary care; it moves clinical psychiatry to a non-patient-contact role; it’s based on a theoretical role originating from outside the specialty; and it looks as if it will perpetuate the very things in need of change. These are goals that have been pushed by Managed Care and PHARMA, hardly by psychiatrists or even its opponents – more like retiring the side than reform. And it’s coming from the APA – the only negotiating force in town. Is this to be the legacy from the 1980 revolution? Is the APA representing psychiatry, our patients, or simply itself and some inappropriate assumptions of power and misguided decisions all along the way? Will practicing psychiatrists continue to leave their fate in the hands of an organization that unilaterally lead us down this path?

British Medical Journal blogby Tom Jefferson7 Oct, 14The European Medicines Agency [EMA] has now released the final version of its policy on the prospective release of clinical reports of trials, which are submitted by sponsors to support marketing authorisation applications [MAAs]. The agency has said that it will—at a future date—determine how to release individual participant data [IPD].

Scope

The policy—to become effective from 1 January 2015—explains what will be released and how. Full clinical study reports will not be released. Rather, selected parts of clinical study reports will be released, including the “core report” [although this is not labelled as such in the text], the statistical analysis plan, protocol and its amendments, and a blank case report form. [To those familiar with clinical study reports, these are sections 1-15, 16.1.1, 16.1.2, and 16.1.9 of the ICH E3 guidelines.] The policy document does not explain why full clinical study reports will not be released.

Redactions

The EMA’s policy states: “The Agency respects and will not divulge CCI [commercially confidential information]. In general, however, clinical data cannot be considered CCI.” That said, commercially confidential information will be redacted, “where disclosure may undermine the legitimate economic interest of the applicant/market authorization holder” and in items that may facilitate identification of trial participants. Sponsors will have primary responsibility for redacting study reports for EMA’s approval prior to their being made accessible under the new policy.

The policy is a landmark, as for the first time it ensures access to clinical study reports of drugs that have obtained a MAA or on which a decision has been made. The EMA may be the first regulator to allow such access and the Nordic Cochrane Centre, the European Ombudsman, and the EMA deserve credit for that.

There’s a lot of good news for researchers in the final version of the policy. Gone is the “Peeping Tom” clause of “viewing only” access to data—described by users of comparable policies as “science through a periscope”—and there is no trace of a threat of legal proceedings for those who produce research that is disagreeable to sponsors.

In a previous post I urged users to adopt Reagan’s maxim of “trust but verify” when reading the EMA’s policies. Ultimately, we will not know how usable and transparent this policy is until it has been in use for some time.

The new president of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, recently moved the responsibility for the regulation of medicines from the health to the industry department. When asked whether this move would allow industry lobbying to affect drug regulations, Ms Bienkowska said, “All my professional experience shows that I am lobbyist-proof. I’m absolutely lobbyist-proof”. Glenis Willmott MEP said, “It is disappointing Ms Bienkowska didn’t answer directly whether or not she thinks pharmaceutical and medical devices should really be in the health commissioner’s portfolio.”

This battle is anything but over. In the other shoe… I ended with a picture of Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli, the author of The Prince – the Renaissance treatise on how to gain and wield power at any cost. I think of him once again this evening. There is no stopping place for the cause of Data Transparency. PHARMA is always in the background. They have unlimited resources and teams of people being well-paid to spend their days working whatever angles are necessary to win the day and allow PHARMA to hold onto control of the data from clinical trials.

This battle is anything but over. In the other shoe… I ended with a picture of Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli, the author of The Prince – the Renaissance treatise on how to gain and wield power at any cost. I think of him once again this evening. There is no stopping place for the cause of Data Transparency. PHARMA is always in the background. They have unlimited resources and teams of people being well-paid to spend their days working whatever angles are necessary to win the day and allow PHARMA to hold onto control of the data from clinical trials.  It’s not paranoia that leads me to this cynical conclusion, it’s self-evident experience. The only thing to say is that their offering this much consistent resistance says that we’re fighting the right battle. And by the way, endless thanks to MEP Glenis Willmott [see on the right track…]. She’s a true champion for the cause [and it is a cause]…

It’s not paranoia that leads me to this cynical conclusion, it’s self-evident experience. The only thing to say is that their offering this much consistent resistance says that we’re fighting the right battle. And by the way, endless thanks to MEP Glenis Willmott [see on the right track…]. She’s a true champion for the cause [and it is a cause]…I wrote this before the last post. Even as I wrote it, I knew I was writing it to myself, mainly to get things straight in my own thinking. But I changed my mind about posting it for two reasons. First, many of you aren’t psychiatrists and may not know the chronology so intimately – and I think it might help. History always seems to help me. Second, there’s something I want to say that has to do with George Dawson’s comment to the last post that won’t make sense without this. I apologize for the redundancies, where I lifted phrases to write the last post.

I was only casually aware of matters psychiatric during the 1960s. For me, it was the era of medical school, Internal Medicine training, and bench research. But from what I recall, the psychiatric residents got a generous government bonus for choosing the specialty. There was a shortage, it seems. In retrospect, that was because of de·Institionalization, and psychiatrists were needed to staff the Mental Health Centers that were to take their places as patients were moved from the hospitals into the community. By the latter half of the 1970s when I was in psychiatric training and early on the faculty, public mental health services were in crisis as the community services and hospital resources disappeared, even as the patient load from de·Institionalization grew [it was before they started filling up the jails and prisons]. Within psychiatry, there was a backlash against the prominence of psychoanalysts. Outside of psychiatry, the criticisms of psychiatry had a broad base: the heavy use of medications in treating psychosis; both the psychoanalytic and medical models; charging third party payers for psychotherapies; the question of whether mental illness was disease; the power of psychiatrists in involuntary commitment and medication. It was a tumultuous time. In the background, the revision of the diagnostic manual was marching towards release in 1980, a force that would make massive changes in the specialty and its practice. One part of that oft-told story is that those changes in psychiatry were orchestrated by the American Psychiatric Association [APA] under the guidance of its Board of Trustees, its Medical Director Dr. Melvin Sabshin, the chair of the DSM-III Task Force, Dr. Robert Spitzer, and the strong influence of the neoKraepelinians centered at Washington University in Saint Louis. Dr. Sabshin further consolidated the power of the APA by founding the American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. [APPI].

The course of psychiatry in the US has been steered by the American Psychiatric Association since those 1980 changes. I don’t know if that central control was present before then, but it has certainly been true during my time. Many of us have withdrawn our membership for a variety of reasons in that time period. The medical·ization and medicine·ization of the specialty built through the ensuing quarter century, an era when much of academic and organized psychiatry was actively engaged with the pharmaceutical industry and the neuroscientific focus of the NIMH. It was a period of dramatic change with third party payers paying psychiatrists for outpatient medication management, and contracting with other specialties for psychosocial treatments. Another change – our prisons filled with chronic mental patients creeping toward the numbers of the confined prior to de·Institionalization.

The first decade of the new century began at the apogee of the now aging new psychiatry. The APA embarked on a DSM Revision that would realize a dream of connecting clinical diagnosis with measurable biology. Dr. Tom Insel of the NIMH advocated reframing psychiatry as Clinical Neuroscience. And the pharmaceutical industry was maintaining a steady pipeline of new medications coming onto the market [along with a publishing arm of its own]. But by the end of the decade, things were once again changing dramatically, as we all know. The involvement of academic psychiatrists with industry came to public attention with the revelations of Senator Grassley about unreported income, but the focus soon generalized to the whole issue of a corrupted alliances between a prominent sector of psychiatry and drug manufacturers – and we began to learn about ghost writing, and guest authorship, and industry financing out-front and in the background. Suits against pharmaceutical companies flourished exposing false advertising, exaggerated efficacy, minimizing of adverse reactions, and the involvement of the "KOLs" with industrial interests which became a source of public shame for us all. Meanwhile, the enthusiasm for a "biologic" DSM-5 choked in a desert of non-confirmation. Then the pipeline dried up, and PHARMA began to exit CNS drug development en masse. Quite an impressive decade of changes in fortune.

Here at the near midpoint of the second decade of the century, it would be hard to summarize the current state of play. We’ve seen several years of intense efforts to reform the clinical trials of drugs through Data Transparency, though at least in psychiatry, at present there’s not a lot of actual action in that arena with a dry pipeline – so, the "closing the stable door after the horse has bolted" adage seems to apply. The DSM-5 effort mercifully limped to its lackluster conclusion, but not before being abandoned by the NIMH, now creating a diagnostic system of its own – the Research Domain Criteria project [RDoC]. If anything, the DSM-5 Task Force process exposed the APA to further scorn – particularly with it’s chairman being exposed as involved in an entrepreneurial enterprise. And to complexify matters further, there’s another huge general issue on the table at the moment, the changing landscape of practice, finance, and health policy coming with the Affordable Care Act [ACA] among other things.

In my home town, there was a 19th century bridge across the Tennessee River. It was designed with bolts that were intended to be tightened and loosened with the seasons, but that never happened. Over a 90 year period, the subtle stresses and strains of seasonal expansion and contraction rendered it unsafe for auto traffic – unfixable. It’s now a tourist attraction as a pedestrian bridge.

In my home town, there was a 19th century bridge across the Tennessee River. It was designed with bolts that were intended to be tightened and loosened with the seasons, but that never happened. Over a 90 year period, the subtle stresses and strains of seasonal expansion and contraction rendered it unsafe for auto traffic – unfixable. It’s now a tourist attraction as a pedestrian bridge.

The APA’s DSM-III revision in 1980 ultimately lead mainstream psychiatry to an exclusively biological focus and a deep entanglement with the pharmaceutical industry. My primary "dog in this hunt" has been the resulting corruption of the industry sponsored clinical drug trials in our peer reviewed psychiatric literature, and the collusion of the academic KOLs who signed on as authors. But the ‘subtle stresses and strains‘ from the ensuing three plus decades of inattention to the traditional domains of psychiatry have taken their toll in many arenas, and left the specialty ill prepared for the challenge of a dramatic change in the healthcare landscape and a growing disillusionment with the medication-heavy approach to matters mental.

Beginning in 2007 when Senator Grassley exposed a number of academic psychiatrists who were failing to report personal drug-company income, there followed a steady stream of revelations of scientific misbehavior and corrupt practices eroding confidence in psychiatry in general. Then, the exit of PHARMA from CNS drug development three years ago took things from bad to worse. The DSM-5 Revision had begun life a decade earlier dreaming of a triumphant transition to a biologically based diagnostic system, but floundered in a desert of non-confirmation – limping to its release barely even revised. Periods of paradigm exhaustion in science are rarely smooth, but this one has been abetted by disillusioning revelations and a reactionary and paralyzed establishment unwilling to deal directly with much of anything.

PsychiatricNewsby Vabren WattsSeptember 15, 2014

PsychiatricNewsby Mark MoranSeptember 23, 2014

PsychiatricNewsFrom the Presidentby Hunter McQuistion and Paul SummergradSeptember 26, 2014

PsychiatricNewsFrom the Presidentby Jurgen Unützer and Jeffrey LiebermanNovember 12, 2013

All healthcare specialties are currently trying to figure out how to fit into the new world of the Affordable Care Act – adapting their traditional identities to a new set of rules and a new theater of operations. Psychiatry doesn’t have that luxury – more starting from scratch, trying to create a new brand – a consultative identity that is as yet amorphous and very different from medication manager of recent years or the general psychiatrist of the past. It’s hard to see through the upbeat rhetoric what they envision psychiatrists actually spending their time doing, or if the primary care physicians they plan for psychiatrists to collaborate with are interested, or if psychiatrists are interested in filling that particular role. And it’s unknown how [or if] they intend to address the widespread misadventures of their predecessors – those longstanding ignored stresses and strains.

by

In this study published on September 15, Arnedo et al. asserted that schizophrenia is a heterogeneous group of disorders underpinned by different genetic networks mapping to differing sets of clinical symptoms. As a result of their analyses, Arnedo et al. have made remarkable and perhaps unprecedented claims regarding their capacity to subtype schizophrenia. This paper has received considerable media attention. One claim features in many media reports, that schizophrenia can be delineated into “8 types”. If these claims are replicable and consistent, then the work reported in this paper would constitute an important advance into our knowledge of the etiology of schizophrenia.

Unfortunately, these extraordinary claims are not justified by the data and analyses presented. Their claims are based upon complex [and we believe flawed] analyses that are said to reveal links between clusters of clinical data points and patterns of data generated by looking at millions of genetic data points. Instead of the complexities favored by Arnedo et al., there are far simpler alternative explanations for the patterns they observed. We believe that the authors have not excluded important alternative explanations – if we are correct, then the major conclusions of this paper are invalidated.

Analyses such as these rely on independence in many ways: among variables used in prediction, absence of artifactual relationships between genotypes and clinical variables, and between the methods of assessing significance and replication. Below we identify five specific areas of concern that are not adequately addressed in the manuscript, each of which calls into question the conclusions of this study.

A. Ancestry/population stratification…B. X chromosome [chrX]…C. Linkage disequilibrium [LD]…D. SNP selection…E. Replication…Conclusions: Given the remarkable claims made by Arnedo et al., it is essential that alternative explanations be excluded. Unfortunately, the authors do not provide the necessary evidence. As presented, their methodology is opaque [even to experts], meaning that their results cannot be independently validated. Arnedo et al. do not consider alternative explanations for the phenomena that they observe, such as confounding from ancestry and LD, even though these are well-known issues for the statistical methods that they employ and have been studied extensively in the statistical and population genetics literature. In addition, their multistep analysis approach is subject to multiple issues as noted above. We believe that it is highly likely that the results of Arnedo et al. are not relevant for schizophrenia. We urge great caution in the interpretation of the results of study.

watching a Battle of the Titans. At least that’s where I am when it comes to this kind of research. The criticisms in A-F above that I left out of my summary are far reaching – untested confounding factors like ancestry and gender, faulty analytic and statistical methodology, replication errors. And their conclusion…

watching a Battle of the Titans. At least that’s where I am when it comes to this kind of research. The criticisms in A-F above that I left out of my summary are far reaching – untested confounding factors like ancestry and gender, faulty analytic and statistical methodology, replication errors. And their conclusion…But the main thing I wanted to write about was PubMed Commons – something whose power I hadn’t quite realized Heretofore, once an article was posted in PubMed, it may have had a few things appended over time. Retracted articles were usually annotated. If there were published letters, they might be referenced with links. But it required journal access to see the letters and they were slow in coming. So a questionable article often languished for many months before any sign of the dissent showed up, if it showed up at all. Many of the disreputable industry funded clinical trials have nothing in PubMed to let a reader know of the problems. In the case above, an international consortium was on the case within two weeks. Take a look. Then look at the infamous Paxil Study 329 with the old links above, and the new below, a comment added when PubMed Commons went live a year ago. Here’s Dr. Karen Dineen Wagner’s write-up about an equally questionable pair of Zoloft trials with many links, but no comment [just waiting for the comments it deserves]. Any author indexed in PubMed can open a Commons Account and leave a comment. Among the major contributors to the problem with clinical trials of the psychiatric drugs, first was that no one much was looking, but even if they were, there was no easy public way to post comments to flag the literature.

It’s easy to get discouraged when reforms that seem so obviously right move so slowly or come in only an incomplete form [beyond the blind…, what we claim to be…], but probably the most important thing isn’t necessarily the enduring safeguards, but rather the ongoing awareness and the mechanisms to alert people to instances that need attention. Right now, there’s a heightened awareness of the problems in our literature. But what matters is that the vigilance lasts beyond the news cycle and we don’t have to look at empty spaces like this anymore:

by Pat BrackenWorld Psychiatry. 2014 13[3]:241-243.…

TOWARDS HERMENEUTICSI contend that good psychiatry involves a primary focus on meanings, values and relationships, both in terms of how we help patients as well as identifying from whence their problems arise. This is not to deny that psychiatry should be a branch of medicine, or that other doctors sometimes deal with problems of meaning. However, interpretation and "making sense" of the personal struggles of our patients are to psychiatry what operating skills and techniques are to the surgeon. This is what makes psychiatry different from neurology. When we put the word "mental" in front of the word "illness", we arc demarcating a territory of human suffering that has issues of meaning at its core. This simply demands an interpretive response from us. 1 think that many psychiatrists would recoil from the idea that they should train themselves to be uninterested in the problems of their patients, as the New York Times interviewee described.Hermeneutics is based on the idea that the meaning of any particular experience can only be grasped through an understanding of the context [including the temporal context] in which a person lives and through which that particular experience has significance. It is a dialectical process whereby we move towards an understanding of the whole picture by understanding the parts. However, we cannot fully understand the parts without understanding the whole. The German philosopher H.-G. Gadamer suggested that the idea of hermeneutics is particularly relevant to the work of the psychiatrist.

By adopting a hermeneutic approach to epistemology, we can attempt to understand the struggles of our patients in much the same way as we attempt to understand great works of art. To grasp the meaning of Picasso’s Guernica, for example, we need to understand what is happening on the canvas, how the artist manages to create a sense of tension and horror through the way he uses line, colour and form. We also need to understand where this painting fits in relation to Picasso’s artistic career, how his work relates to the history of Western art and the political realities of his day that he was responding to in the painting. The meaning of the work emerges in the dialectical interplay of all these levels and also in the response of the viewer. The actual physical painting is a necessary, but not a sufficient, factor in generating a meaningful work of art. A reductionist approach to art appreciation would involve the unlikely idea that we could reach the meaning of a painting through a chemical analysis of the various pigments involved.

CONCLUSIONI do not believe that we will ever be able to explain the meaningful world of human thought, emotion and behaviour reductively, using the "tools of clinical neuroscience". This world is simply not located inside the brain. Neuroscience offers us powerful insights, but it will never be able to ground a psychiatry that is focused on interpretation and meaning. Indeed, it is clear that there is a major hermeneutic dimension to neuroscience itself. A mature psychiatry will embrace neuroscience but it will also accept that "the neurobiological protect in psychiatry finds its limit in the simple and often repeated fact: mental disorders are problems of persons, not of brains. Mental disorders are not problems of brains in labs, but of human beings in time, space, culture, and history."hat tip to Mad in America…

For most of my career, I was comfortable with the term «mind·brain dichotomy». Actually, it wasn’t anything I gave much thought. It was just a descriptor – a way of separating two areas that I knew something about. I didn’t pay attention to the «mind·brain dichotomy» part, as in mutual exclusivity or contrast. My primary interests were in the «mind·brain dichotomy» part, but that didn’t mean I didn’t care about the «mind·brain dichotomy» part. I was certainly aware that in the halls and meetings of psychiatry and psychology, this was a true «mind·brain dichotomy» and the controversy was endless. Mainstream psychiatrists like APA presidents and NIMH Directors were careful to always say brain diseases or even clinical neuroscience, and critics raled against the bio·bio·bio medical model. I frankly thought it was all a bunch of turf fighting with the many psychiatrists asserting their "medical·ness" and way overdoing the whole neoKraepelinian thing, perpetuating their war with the psychoanalysts, and the critics were on the same tack as Dr. Szasz and the 1970s behaviorists. The battling feels anachronistic, like straw man arguments, to me, and I try to avoid it whenever possible in line with my life rule, "never accept an invitation to go crazy."

But as an older retired psychiatrist, I have had other thoughts. I now think that explicitly or implicitly dichotomizing brain disease or human psychological processes is only destructive, and that it is a «false dichotomy» in the end. I personally think that the psychotic mental illnesses are likely biologically determined, or at least have prominent biological determinants. I don’t know that like I do about Systemic Lupus Erythematosis [SLE], but it’s what I think. I would be likely to use medications in cases of psychotic illness, but not because I think I’m treating the underlying cause. I would be using them because psychosis can be disruptive to the person’s life and sometimes fatal, and the medicine can help with that. I’m way on the side of using medications only when there’s a reason and not as a maintenance. The drugs are too toxic for maintenance and there’s increasing evidence that less is better in the long term [I think of Lithium as an exception to that statement]. I think the same thing about Lupus. Steroids or immunosuppressives don’t treat whatever Lupus is [like Vitamin C treats Scurvy]. They treat the damage to the body by suppressing the pathological immunological mechanisms. Antipsychotics can suppress psychotic damage, also a mechanism of disease. The analogy goes further in that. Both steroids and antipsychotics are toxic, dangerous, and not for casual or prolonged use. But that has nothing to do with the minds of these patients. I happen to think many patients with the schizophrenic illnesses are candidates for a kind of psychotherapy adapted to their specific mentation – and that it involves their learning to live with the difficulties in abstraction, emotional experience, and their propensity to psychotic reactions in the face of life’s confusions. Those patients have minds too and often need [and want] help with some aspect of their mental life, on meds or not [by the way, adaptive counseling often helps Lupus patients live with their illness as well\.

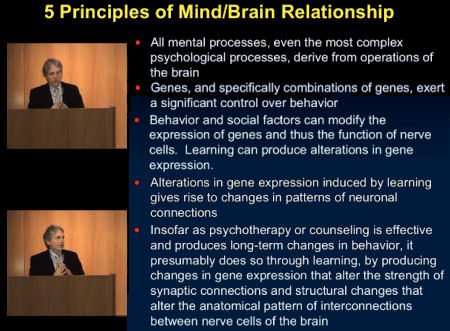

So as much as I like Dr. Bracken and as much as I agree with "I do not believe that we will ever be able to explain the meaningful world of human thought, emotion and behaviour reductively, using the "tools of clinical neuroscience", and even though I say things like that sometimes, I’m trying to get over doing it. And as much as I am infuriated when Dr. Nemeroff flashes slides that say things like this implying that he knows something the rest of us don’t:

I say let him think what he thinks. I doubt that many are listening much anymore.

I realize that in this piece, Dr. Bracken is reacting to people like Dr. Nemeroff, Dr. Insel, and many of the mainstream psychiatrists who have dehumanized psychiatry and tried to make an unleapable leap. He’s part of a group that call themselves the Critical Psychiatry Network for that very reason. But I think they make a mistake to even engage with those people on the other side, as destructive as they can sometimes be. There are destructive forces on both sides [and will be so long as the notion of "sides" persists]. Dr. Bracken and others in this group have so much to teach us, to restore a rational balance, but not by arguing with the caricatured enemy. The biologists and neuroscientists have much to teach us too, at least some of them do, and I look forward to learning about it when they get it straight.

I was kind of surprised how much letting the EMA decisions sit for a day softened my reaction, because my first take was to catalog what was missing from my wish list and privately groan [worry…, beyond the blind…]. I’m hungry too. And so there was more reflection to be done, and what I came up with may well be idiosyncratic – but that’s not for me to decide. So I’ll just say what I think.

I think what happened with PHARMA and Medicine was at least as much our own fault as PHARMA’s, and I’m including myself in the indictment. I’m not talking about the KOLs or in the case of psychiatry, the ones who jumped into the quick visit/psychopharmacology-for-symptoms mode because it was lucrative or because "it just was what happened." They deserve whatever blame comes their way. I’m talking about all of us who passed responsibility to others to maintain a standard of scientific integrity and medical ethics. We just didn’t pay attention.

When the great reform of requiring clinical trials came along in 1962, it was seen as a plan that would keep PHARMA honest. It worked for a while and we stopped looking. In psychiatry, when the DSM-III came along, it made an equal place for the biological side of the equation, but opened the door to making that the only side. It was obvious the day it was published, but we didn’t keep on top of it. When the CROs and PHARMA took control of Clinical Trials, we just didn’t pay attention. Many of us didn’t even notice. When the reform of ClinicalTrials.gov was added, PHARMA basically ignored many parts of it, mostly the reporting requirements, and that continued even when they were strengthened. We acted like reforms solved the problem, and ignored the fact that such things need constant monitoring – because the response to reforms from the other side is to evolve creative solutions that undermine their essence. And like what happened to the great reform of state mental hospitals, things festered when they were out of sight and out of mind.

At least in medicine, there have been some watchdogs along the way: David Healy, Bernard Carroll, Bob Rubin, Danny Carlat come quickly to mind in psychiatry, but they are exceptions in a sea of sheep who didn’t pay enough attention to the wolves in drag wandering among the flock. So in my view, we can’t expect the EMA, or NICE, or the FDA to maintain the scientific and ethical standards of medicine or psychiatry. The forces of Hospital Corporations, Managed Care, Governmental Agencies, and the Pharmaceutical and Device Industries are powerful, but they all feed off of medicine. Only medicine can provide the required ongoing oversight, and we just haven’t done it. The "good guys" have been so quiet that many have forgotten that there are still any left.

EMA adopts landmark policy to take effect on 1 January 2015Press releaseOctober 2, 2014The European Medicines Agency [EMA] has decided to publish the clinical reports that underpin the decision-making on medicines. Following extensive consultations held by the Agency with patients, healthcare professionals, academia, industry and other European entities over the past 18 months, the EMA Management Board unanimously adopted the new policy at its meeting on 2 October 2014. The policy will enter into force on 1 January 2015. It will apply to clinical reports contained in all applications for centralised marketing authorisations submitted after that date. The reports will be released as soon as a decision on the application has been taken.

“The adoption of this policy sets a new standard for transparency in public health and pharmaceutical research and development,” said Guido Rasi, EMA Executive Director. “This unprecedented level of access to clinical reports will benefit patients, healthcare professionals, academia and industry.”

The new EMA policy will serve as a useful complementary tool ahead of the implementation of the new EU Clinical Trials Regulation that will come into force not before May 2016. EMA expects the new policy to increase trust in its regulatory work as it will allow the general public to better understand the Agency’s decision-making. In addition, academics and researchers will be able to re-assess data sets. The publication of clinical reports will also help to avoid duplication of clinical trials, foster innovation and encourage development of new medicines.

According to the policy’s terms of use, the public can either browse or search the data on screen, or download, print and save the information. The reports cannot be used for commercial purposes. In general, the clinical reports do not contain commercially confidential information. Information that, in limited instances, may be considered commercially confidential will be redacted. The redaction will be made in accordance with principles outlined in the policy’s annexes. The decision on such redactions lies with the Agency.

The policy will be implemented in phases. The first phase starts on 1 January 2015. Once a medicine has received a marketing authorisation, EMA will publish the clinical reports supporting applications for authorisation of medicines submitted after the policy’s entry into force. For line extensions and extensions of indications of already approved medicines, the Agency will give access to clinical reports for applications submitted as of 1 July 2015 after a decision has been taken.

In future, EMA plans to also make available individual patient data. To address the various legal and technical issues linked with the access to patient data, the Agency will first consult patients, healthcare professionals, academia and industry. It is critically important for EMA that the privacy of patients is adequately protected before their data are released.

The policy does not replace the existing EMA policy on access to documents. It will be reviewed in June 2016 at the latest.

There are four documents generated from a Clinical Trial: a Protocol, the CRFs [Case Report Forms], the IPD [Individual Participant Data], the CSR [Clinical Study Report]. Oh yeah, I guess we could add the published [or maybe unpublished] journal article, bringing the total to five documents [see it matters…]. In the absence of outright fraud, three of them come from "behind the blind," in other words, they are what the investigators [and sponsors] see when the "blind is broken." If you have those three things, the playing field is level. Someone evaluating the study from afar is in the same boat as those who did it. We’re talking about a gajillion pages [every piece of paper from every visit by every subject, the CRFs, AND the tables compiled into the IPD of everything that can be objectified and tabulated]. It’s an overwhelming stack of stuff.

After the blind is broken and the data is at hand, it is collated, analyzed, and turned into the CSR – a manageable report for regulators that will later be simplified further to become a journal article [or not]. While there are plenty of computers whirring at this point in the process, there are real live people with real live motives also in the mix, and this is where the problems have come from – beyond the blind:

The Internet tells me that this phrase comes from 18th century England [when a penny was serious money]. Pennies were frequently counterfeited in those times. So if if one turned up in one’s purse, it was spent quickly. There were so many in circulation that you were likely to get another one soon. Thus, "turns up like a bad penny" – something unwanted of dubious value that keeps showing up.

The Internet tells me that this phrase comes from 18th century England [when a penny was serious money]. Pennies were frequently counterfeited in those times. So if if one turned up in one’s purse, it was spent quickly. There were so many in circulation that you were likely to get another one soon. Thus, "turns up like a bad penny" – something unwanted of dubious value that keeps showing up.

by Gibbons RD, Coca Perraillon M, Hur K, Conti RM, Valuck RJ, and Brent DAPharmacoepidemiologic Drug Safety. 2014 Sep 29. doi: 10.1002/pds.3713. [Epub ahead of print]

PURPOSE: In the 2004, FDA placed a black box warning on antidepressants for risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior in children and adolescents. The purpose of this paper is to examine the risk of suicide attempt and self-inflicted injury in depressed children ages 5-17 treated with antidepressants in two large observational datasets taking account time-varying confounding.METHODS: We analyzed two large US medical claims databases (MarketScan and LifeLink) containing 221,028 youth (ages 5-17) with new episodes of depression, with and without antidepressant treatment during the period of 2004-2009. Subjects were followed for up to 180 days. Marginal structural models were used to adjust for time-dependent confounding.RESULTS: For both datasets, significantly increased risk of suicide attempts and self-inflicted injury were seen during antidepressant treatment episodes in the unadjusted and simple covariate adjusted analyses. Marginal structural models revealed that the majority of the association is produced by dynamic confounding in the treatment selection process; estimated odds ratios were close to 1.0 consistent with the unadjusted and simple covariate adjusted association being a product of chance alone.CONCLUSIONS: Our analysis suggests antidepressant treatment selection is a product of both static and dynamic patient characteristics. Lack of adjustment for treatment selection based on dynamic patient characteristics can lead to the appearance of an association between antidepressant treatment and suicide attempts and self-inflicted injury among youths in unadjusted and simple covariate adjusted analyses. Marginal structural models can be used to adjust for static and dynamic treatment selection processes such as that likely encountered in observational studies of associations between antidepressant treatment selection, suicide and related behaviors in youth.

The statistical analysis was comprised of two stages. In the first stage, a logistic regression model was used to predict antidepressant usage on each of the 6months conditional on fixed covariates (demographics and prior suicide attempt and self-inflicted injury) and time-varying covariates (comorbid conditions, concomitant medications (listed above), psychiatric hospitalizations and psychotherapy above). The predicted probability of treatment at time point t was computed as the continued product of probabilities from baseline to time point t . The inverses of these estimated probabilities were then used as weights W(t) in the second stage analysis that related actual treatment (dynamcally determined on a month by month basis) to suicide attempt and self-inflicted injury using a discrete time survival model. In practice, W(t) is highly variable and fails to be normally distributed. To overcome this problem, Robins suggested use of the stabilized weight:where L is the set of all baseline and time-varying covariates, V is a subset of L consisting of only the baseline covariates (i.e. time invariant effects), A(k) is the actual treatment assignment at time k , and à (k) is the treatment history…

The paper is based on the analysis of two large longitudinal claims databases from which they extracted a number of covariates. He describes, but does not show, his analyses which I couldn’t exactly follow, but he could disappear the correlation between SSRIs and suicidality by his factor analysis. And like many of his papers, there’s nothing to say [because there’s nothing to see]. And like so much of his work, in spite of all the jargon, the only way there is to accept his conclusions is to take them on faith. I’m not willing to do that based on vetting his previous work [cataloged above]. As Neuroskeptic tweeted:

|

the thing is, I might be willing to buy Gibbons et al’s argument about confounding, *but* I just can’t trust… |

|

…him to present an unbiased analysis of the data, judging by what I’ve seen of the "CAT"…. |

| [see Can A Computer Measure Your Mood? (CAT Part 3)] |

Well I certainly agree, but my skepticism goes further – beyond his CAT work, and the conduct of many of the studies on the list. Besides his practiced opaqueness and monotonous conclusions, I doubt that any population study of the problem of Akathisia and suicidality will ever shed any meaningful light on this question based on clinical experience. I’ve seen cases of agitation, and suicidality, and know of several related completed suicides. The most common version is a patient who gets put on an SSRI and becomes agitated, aggressive and they stop taking it either themselves or at the request of their parents – and they never go back to see the person that prescribed it. So they wouldn’t show up at all in a longitudinal population database. If you’re a clinician and you’ve seen these cases, even though they’re infrequent, you have no questions about the syndrome. It’s not subtle. These population studies use suicidality and completed suicides as an end-point rather that the full range of the presentations of Akathisia.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work was supported by NIMH grant MH8012201 (RDG) and AHRQ grants 7U19HS021093-03 (RDG) and T32HS000084 (MCP)… Dr. Gibbons has been an expert witness in suicide cases for the US Department of Justice, Wyeth and Pfizer.