During my forty years of an active medical career, I don’t recall thinking about the Food and Drug Administration [FDA] or, for that matter, the Clinical Trials of medications – even though they became obligatory about the same time I started medical school [1962] in the wake of the Thalidomide problem. Whenever there was a new drug I wasn’t familiar with, I opened the PDR and read the efficacy and adverse effects sections, assuming they were accurate. I generally stayed on the "trailing edge" of new drugs, preferring the familiarity of experience to "the latest." And, to be honest, my own prescribing from the late 1970s through retirement was minimal. Had there been an exam on the FDA approval process, I would’ve flunked it. That said, I’ve always been a medical literature junkie, but my reading has been focused on the things I was actually doing – and psychopharmacology wasn’t it. So there has been a lot of catching up to do in the last few years.

The idea of Randomized Clinical Trials [RCTs] for testing drugs makes perfect intuitive sense, particularly in psychiatry where the outcomes are subjective responses measured by standardized rating scales. Start with an a priori protocol describing the conduct of the whole study in detail – including the outcome variables, the analytic techniques, and criteria for the conclusions – and the trial should run itself. But looking at the process now fifty years later, things are anything but that simple. The story is one of recurrent regulatory reform to tighten the process countered by the creative exploitation of loopholes – a high stakes game played on the tables of medicine. And like any such gambling enterprise, it hinges on holding one’s cards close to the chest – on secrecy.

by Deborah A. Zarin, M.D., Tony Tse, Ph.D., and Jerry Sheehan, M.S.New England Journal of Medicine. 2015 372:174-180.

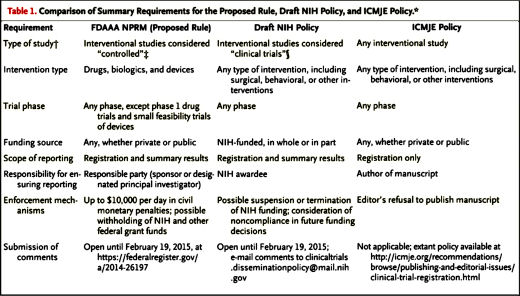

Broad access to information about clinical trials and their findings is critical for advancing medicine, promoting public health, and fulfilling ethical obligations to human volunteers. Traditional methods of information dissemination [e.g., presentations and publication] may nevertheless leave distortions and gaps in the knowledge base because the results of many trials are not published. Title VIII of the Food and Drug Administration [FDA] Amendments Act of 2007 [FDAAA] addressed some of these concerns by requiring the registration and submission of summary results information to ClinicalTrials.gov for certain clinical trials of drugs [including biologic products] and devices. The Department of Health and Human Services [HHS] recently published for public comment a proposed rule [or “Notice of Proposed Rulemaking [NPRM] for Clinical Trials Registration and Results Submission”] to clarify and expand [as permitted] the FDAAA requirements and ultimately facilitate compliance with the law. Separately, and in keeping with a long-standing principle that systematic dissemination of results is a critical step in realizing the value of the research investment, the National Institutes of Health [NIH] has issued a draft policy for public comment to promote registration and results submission to ClinicalTrials.gov. This policy is proposed to cover all NIH-funded clinical trials, regardless of study phase, type of intervention, or whether they are subject to the FDAAA requirements.

-

As intuitive as RTCs seem, even when they’re run and published in a pristine manner, they are anything but a gold standard for measuring the effectiveness or the safety of a drug or device. They’re short term. The subjects are carefully picked and more closely watched than in clinical practice. They are capable of detecting significant differences that are well below the threshold of clinical relevance. And particularly in the domain of adverse events, their getting on first results are often interpreted as a home run. And they have offered a conduit for some of the most egregious deceit in the history of medicine. For my money, the best treatise on this topic remains David Healy’s Pharmageddon.

-

The Results Database is a summary tool, not full Data Transparency. It can be helpful in vetting a Clinical Trial, particularly if the verbatim protocol is available. Many of the techniques used to distort results in published papers rely on the HARK technique [Hypothesis After Results Known] – poring over the numbers looking for something significant after the fact. But the more subtle techniques that play with data display or analysis can be buried in the summary just as in the published material. So it can be considered a step forward, but it doesn’t replace the kind of Data Transparency we really want – the raw data prior to any opportunity for manipulation [emphasis on any].

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.