STAR*D was an elaborate NIMH study aiming to define some sequencing method that would improve the response to antidepressants using the algorithm on the left [as seen from space]. The main outcomes were a database mined for several hundred publications, a self-rating depression scale [QIDS-SR], and a template for future studies called naturalistic at the time – no control group, no blinding, and progress was monitored by a telephone version of the QIDS-SR. From my point of view, it was a thirty-five million dollar misunderstanding…

STAR*D was an elaborate NIMH study aiming to define some sequencing method that would improve the response to antidepressants using the algorithm on the left [as seen from space]. The main outcomes were a database mined for several hundred publications, a self-rating depression scale [QIDS-SR], and a template for future studies called naturalistic at the time – no control group, no blinding, and progress was monitored by a telephone version of the QIDS-SR. From my point of view, it was a thirty-five million dollar misunderstanding…

But the idea that there is some way to predict who might respond to which antidepressant definitely has staying power. Borrowing the term

personalized medicine from physical medicine, the search for predictor of response continues. There are two large ongoing studies [

iSPOT-D and

EMBARC] aiming towards locating biosignatures that might predict a response, and they are both beginning to report findings [

Godzilla vs. Ghidorah ,,,, ]. Here’s one from the

STAR*D director reporting on an aspect of

iSPOT-D…

by Bruce A. Arnow, Christine Blasey, Leanne M. Williams, Donna M. Palmer, William Rekshan, Alan F. Schatzberg, Amit Etkin, Jayashri Kulkarni, James F. Luther, and A. John Rush.

American Journal of Psychiatry. 2015 172[8]:743-750.

Objective: The study aims were 1] to describe the proportions of individuals who met criteria for melancholic, atypical, and anxious depressive subtypes, as well as subtype combinations, in a large sample of depressed outpatients, and 2] to compare subtype profiles on remission and change in depressive symptoms after acute treatment with one of three antidepressant medications.

Method: Participants 18–65 years of age [N=1,008] who met criteria for major depressive disorder were randomly assigned to 8 weeks of treatment with escitalopram, sertraline, or extended-release venlafaxine. Participants were classified by subtype. Those who met criteria for no subtype or multiple subtypes were classified separately, resulting in eight mutually exclusive groups. A mixed-effects model using the intent-to-treat sample compared the groups’ symptom score trajectories, and logistic regression compared likelihood of remission [defined as a score ≤5 on the 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology–Self-Report].

Results: Thirty-nine percent of participants exhibited a pure-form subtype, 36% met criteria for more than one subtype, and 25% did not meet criteria for any subtype. All subtype groups exhibited a similar significant trajectory of symptom reduction across the trial. Likelihood of remission did not differ significantly between subtype groups, and depression subtype was not a moderator of treatment effect.

Conclusions: There was substantial overlap of the three depressive subtypes, and individuals in all subtype groups responded similarly to the three antidepressants. The consistency of these findings with those of the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression trial suggests that subtypes may be of minimal value in antidepressant selection.

… that we all already know, since clinical subtype is a usual add-on to any antidepressant Clinical Trial and is regularly unrevealing. Here’s another in the search for biomarkers of antidepressant response:

by Alan F. Schatzberg, Charles DeBattista, Laura C. Lazzeroni, Amit Etkin, Greer M. Murphy, Jr., and Leanne M. Williams

American Journal of Psychiatry. 2015 172[8]:751-759.

Objective:: The ABCB1 gene encodes P-glycoprotein, which limits brain concentrations of certain antidepressants. ABCB1 variation has been associated with antidepressant efficacy and side effects in small-sample studies. Cognitive impairment in major depressive disorder predicts poor treatment outcome, but ABCB1 genetic effects in patients with cognitive impairment are untested. The authors examined ABCB1 genetic variants as predictors of remission and side effects in a large clinical trial that also incorporated cognitive assessment.

Method:: The authors genotyped 10 ABCB1 single-nucleotide polymorphisms [SNPs] in 683 patients with major depressive disorder treated for at least 2 weeks, of whom 576 completed 8 weeks of treatment with escitalopram, sertraline, or extended-release venlafaxine [all substrates for P-glycoprotein] in a large randomized, prospective, pragmatic trial. Antidepressant efficacy was assessed with the 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology–Self-Rated [QIDS-SR], and side effects with a rating scale for frequency, intensity, and burden of side effects. General and emotional cognition was assessed with a battery of 13 tests.

Results:: The functional SNP rs10245483 upstream from ABCB1 had a significant effect on remission and side effect ratings that was differentially related to medication and cognitive status. Common homozygotes responded better and had fewer side effects with escitalopram and sertraline. Minor allele homozygotes responded better and had fewer side effects with venlafaxine, with the better response most apparent for patients with cognitive impairment.

Conclusions:: The functional polymorphism rs10245483 differentially affects remission and side effect outcomes depending on the antidepressant. The predictive power of the SNP for response or side effects was not lessened by the presence of cognitive impairment.

That is one pretty graph –

efficacy on the left, safety on the right, here I am, stuck in the middle with you. This study looked at ten

SNP‘s on a gene that "among blood-brain barrier transporter proteins, P-glycoprotein transports several commonly prescribed antidepressants." It looks like one’s genetics has something to do with antidepressant response.

Lexapro® or

Zoloft® for G/Gs and

Effexor XR® for T/Ts. However, reading the methodology, one wonders. It looks as if they did the honorable thing and corrected to avoid false positives.

To account for the testing of multiple SNPs, SNP p values of 0.05/18<0.0028 ere considered significant using a Bonferroni correction for nine SNPs, each tested for one main effect and one interaction effect. All p values <0.05 are reported for completedness, because of the possibility of false negative results at this significance level.

But buried in the math [which we don’t quite follow], there’s one of those "uh-oh" things:

Remission. In the modified intent-to-treat sample, age [p=0.01] and baseline QIDS-SK score [p<0.001] were significant predictors of remission. Hence, genetic analyses were performed covarying for both.

Within the significant overall model [X2=67.58, df=29, p<0.001] only rsl0245483 contributed significantly to prediction of remission. For rsl0245483, there was a significant main effect on remission using multiple testing correction [W=12.64, p<0.001; main effect odds ratio=3.48] and a significant interaction by treatment arm [W=11.18, p=0.001; interaction odds ratio=1.73]. Common allele homozygotes for rsl0245483 responded significantly better to escitalopram [p=0.032] and sertraline [p=0.020] than did minor allele homozygotes. Minor allele homozygotes responded significantly better to venlafaxine [p=0.018]. There were no effects noted in the heterozygotes. The specific contribution of rsl0245483 as a predictor of remission was also verified in univariate models assessing each SNP one at a time.

The effect was similar in whites and nonwhites. In white participants in the modified intent-to-treat sample [N=423], within the significant overall model [X2=61.51, df=29, p<0.001] rsl0245483 had a significant main effect on remission [W=7.22, p=0.007; main effect odds ratio=3.54] and a significant interaction by treatment arm [W=6.99, p=0.008; interaction odds ratio=1.78], which did not pass the multiple testing threshold. For nonwhites, within the significant overall model [X2=55.79, df=28, p=0.001], there was a main effect of rsl0245483 on remission [W=11.42, p=0.001; main effect odds ratio=14.38] and a significant interaction between rsl0245483 and treatment [W=9.81, p=0.002; interaction odds ratio=3.54] that met the multiple testing correction threshold.

I would like to be competent in looking at those statistics and knowing what they mean, but in genetics studies, I come up short. These studies are often non-replicable, and I’m suspicious this will turn out to be one of those too. First off, there’s no control, no placebo group. So like in STAR*D, we don’t know what those responder figures really mean. And while they say the effect was similar in whites and nonwhites, the rest of that paragraph doesn’t confirm the assertion, including a dramatic difference in the odds ratios. One really has to be suspicious with such a paragraph that there a decepticon in the mix. And speaking of STAR*D, "The authors acknowledge the editorial support of Jon Kilner, M.S., M.A." Jon was the medical writer for most of the STAR*D articles. And the two first authors spent years chasing a glucocorticoid blocker in psychotic depression without results [but lots of profit]. Throw in their extensive COIs including commercial genetic testing labs, the financing of Australian entrepreneur Evian Gordon’s brain resources and suspicion is well justified.

My take on this whole line of thinking is suffused with suspicion. It seems to me that the assumption that there will be biomarkers that predict antidepressant response is widely held, but I’m in the dark as to why. At least this study has a hypothesis – the transport of drugs across the blood-brain barrier. This article is accompanied by a Perspective article from the NIMH Intramural Research Program [Clinically Useful Genetic Markers of Antidepressant Response: How Do We Get There From Here?] that suggests [you guessed it] more research.

STAR*D began in 2001 as an outgrowth of the TMAP program [often referred to as

the infamous  TMAP program

TMAP program] and has spawned a steady stream of both public and industry financed research into super-charging antidepressants ever since – now chasing the dream of predictive genetic biomarkers [which might lead to a productive enterprise in commercial testing]. Meanwhile, back at STAR*D, it looks as if someone’s going to have another shot at it:

Medscape Medical News

by Kenneth Bender

August 14, 2015

… Somaia Mohamed, MD, PhD, VA Connecticut Health Care System, and coauthors of the article describing the VAST-D study credit the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relive Depression [STAR*D] study for highlighting the frequent inadequate response to initial treatments, but point out that the study did not ultimately identify optimal interventions after initial treatment failure.

They also note that the STAR*D study did not include an atypical antipsychotic augmentation treatment arm, because the study was conducted prior to FDA approval of that indication for an agent in this class.

The VAST-D study will incorporate atypical antipsychotic augmentation in the protocol, and the authors indicate that it will answer two principle questions unanswered by STAR*D: "For which patients, under what circumstances, is switching to vs augmenting with other antidepressants the most effective ‘next-step’ strategy, and how does augmentation with atypical antipsychotics compare to either switching or augmenting with antidepressants?"

by Somaia Mohamed, Gary R. Johnson, Julia E. Vertrees, Peter D. Guarino, Kimberly Weingart, Ilanit Tal Young, Jean Yoon, Theresa C. Gleason, Katherine A. Kirkwood, Amy M. Kilbourne, Martha Gerrity, Stephen Marder, Kousick Biswas, Paul Hicks, Lori L. Davis, Peijun Chen, Alexandra Mary Kelada, Grant D. Huang, David D. Lawrence, Mary LeGwin, and Sidney Zisook

Psychiatry Research. Published Online: August 05, 2015

Highlights

- Over 2/3s of Major Depressive Disorder cases do not achieve remission on initial treatment.

- Urgent need to identify effective next step treatments for MDD.

- Switching to bupropion-SR vs. augmenting with bupropion-SR or aripiprazole.

- Compare 12-week remission and relapse for up to 6 months after remission.

- Seven methodological issues to balance efficacy and effectiveness.

Abstract

Because two-thirds of patients with Major Depressive Disorder do not achieve remission with their first antidepressant, we designed a trial of three “next-step” strategies: switching to another antidepressant [bupropion-SR] or augmenting the current antidepressant with either another antidepressant [bupropion-SR] or with an atypical antipsychotic [aripiprazole]. The study will compare 12-week remission rates and, among those who have at least a partial response, relapse rates for up to 6 months of additional treatment. We review seven key efficacy/effectiveness design decisions in this mixed “efficacy-effectiveness” trial.

"Urgent need to identify effective next step treatments for MDD" assumes there is some such "effective next step" hidden somewhere in the current pharmacopeia yet to be identified. That’s an increasingly questionable assumption…

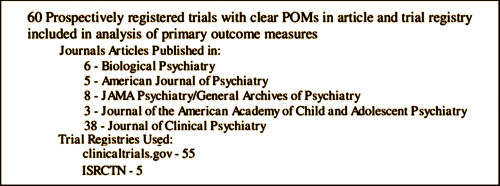

One runs into the most interesting people in the oddest of ways, looking into the most unlikely of topics. Tom Jefferson and Peter Doshi are the Tamiflu guys, the ones that spent years running down an epidemiology story that needed to be told, and at least for me, began to unravel the torturous and kind of boring story of how Clinical Trials are cataloged and documented. Tom is a British Epidemiologist with the Cochrane Collaboration in Rome, Italy. Peter, his colleague, is on our side of the pond in Maryland and now an editor with the BMJ. But this blog isn’t about their interesting story with Tamiflu and other things. It’s about a topic they’ve tried to clarify for all of us – the Clinical Study Reports that become part of the record of Clinical Drug Trials – a should·be·simple topic that’s complex·and·confusing [perhaps deliberately so].

One runs into the most interesting people in the oddest of ways, looking into the most unlikely of topics. Tom Jefferson and Peter Doshi are the Tamiflu guys, the ones that spent years running down an epidemiology story that needed to be told, and at least for me, began to unravel the torturous and kind of boring story of how Clinical Trials are cataloged and documented. Tom is a British Epidemiologist with the Cochrane Collaboration in Rome, Italy. Peter, his colleague, is on our side of the pond in Maryland and now an editor with the BMJ. But this blog isn’t about their interesting story with Tamiflu and other things. It’s about a topic they’ve tried to clarify for all of us – the Clinical Study Reports that become part of the record of Clinical Drug Trials – a should·be·simple topic that’s complex·and·confusing [perhaps deliberately so].

… In June, I arranged for the Board of Trustees to tour San Quentin in northern California. It was a powerful, moving, and formative experience, and I’m thankful to Dr. Paul Burton, the chief psychiatrist, and to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation for giving us that access. Our visit was important because, if one wants to understand firsthand the toll mental illness is taking on our country, one just needs to peer beyond the bars of our nation’s jails and prisons. It’s also important to have a detailed and nuanced understanding of the situation. Our tour was a no-holds-barred look at San Quentin State Prison. For three hours, we were shown various aspects of prison life…. We specifically saw the psychiatric facilities, which are highly used by the inmates. In many ways they are state of the art. As you’d expect, sharp angles in the halls and cells, down to the door hinges and door handles, were filed smooth to prevent inmates from using them to aid in a suicide attempt. Many cells provided a sanctuary for inmates, nearly always curled up on a plain bed with a blanket covering them head to toe.

… In June, I arranged for the Board of Trustees to tour San Quentin in northern California. It was a powerful, moving, and formative experience, and I’m thankful to Dr. Paul Burton, the chief psychiatrist, and to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation for giving us that access. Our visit was important because, if one wants to understand firsthand the toll mental illness is taking on our country, one just needs to peer beyond the bars of our nation’s jails and prisons. It’s also important to have a detailed and nuanced understanding of the situation. Our tour was a no-holds-barred look at San Quentin State Prison. For three hours, we were shown various aspects of prison life…. We specifically saw the psychiatric facilities, which are highly used by the inmates. In many ways they are state of the art. As you’d expect, sharp angles in the halls and cells, down to the door hinges and door handles, were filed smooth to prevent inmates from using them to aid in a suicide attempt. Many cells provided a sanctuary for inmates, nearly always curled up on a plain bed with a blanket covering them head to toe.