And so another atypical antipsychotic may be dripping from the FDA Approval pipeline…

Lundbeck Press Release

September 24, 2014

H. Lundbeck A/S [Lundbeck] and Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. [Otsuka] today announced that the US Food and Drug Administration [FDA] has determined that the New Drug Application [NDA] for brexpiprazole for monotherapy in adult patients with schizophrenia and for adjunctive treatment of major depressive disorder [MDD] in adult patients is sufficiently complete to allow for a substantive review and the NDA is considered filed as of 9 September 2014 [60 days after submission]. The PDUFA date is July 11, 2015…

PsychiatricNews

April 17, 2015

New findings from a phase 3 clinical trial, published today in AJP in Advance, suggest that a recently developed antipsychotic may prove to be one of the next treatments for schizophrenia. Researchers from the Department of Psychiatry at Hofstra North Shore-LIJ School of Medicine conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with 636 patients with schizophrenia to investigate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of brexpiprazole—a serotonin-dopamine activity modulator that acts as a partial agonist at serotonin 5-HT1A receptors and dopamine D2 receptors, while antagonizing serotonin 5-HT2A receptors and noradrenaline alpha receptors…

“It is important for clinicians and patients to have a range of treatment options to manage symptoms effectively and safely … as response to therapy can vary greatly from individual to individual and from one medication to the next.” Correll informed Psychiatric News that the Food and Drug Administration will make its final decision about the approval of brexpiprazole for the treatment of schizophrenia as well as major depressive disorder in July…

I thought it might be interesting in the light of all of our enthusiasm for Data Transparency and other reforms to take a look at the Clinical Trials for Brexpiprazole and see how they stack up with some of the suggested changes:

Clinicaltrials.gov has 30 entries for Brexpiprazole, 25 being Phase 3. They’re obviously aiming for the adjunctive-antidepressant market [which must be much larger than the schizophrenia market]. They don’t get high marks in the Clinical Trial Results Database in that none of the completed studies have results posted [at least 8 completed over a year ago]. Here are the two recently published studies in Schizophrenia which I presumes are the ones being submitted to the FDA for approval [

each study listed 60 locations as clinical sites!]:

by Correll CU, Skuban A, Ouyang J, Hobart M, Pfister S, McQuade RD, Nyilas M, Carson WH, Sanchez R, and Eriksson H.

American Journal of Psychiatry. 2015 Apr 16 [Epub ahead of print]

OBJECTIVE: The efficacy, safety, and tolerability of brexpiprazole and placebo were compared in adults with acute schizophrenia.

METHOD: This was a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Patients with schizophrenia experiencing an acute exacerbation were randomly assigned to daily brexpiprazole at a dosage of 0.25, 2, or 4 mg or placebo [1:2:2:2] for 6 weeks. Outcomes included change from baseline to week 6 in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale [PANSS] total score [primary endpoint measure], Clinical Global Impressions Scale [CGI] severity score [key secondary endpoint measure], and other efficacy and tolerability measures.

RESULTS: The baseline overall mean PANSS total score was 95.2, and the CGI severity score was 4.9. Study completion rates were 62.2%, 68.1%, and 67.2% for patients in the 0.25-, 2-, and 4-mg brexpiprazole groups, respectively, versus 59.2% in the placebo group. At week 6, compared with placebo, brexpiprazole dosages of 2 and 4 mg produced statistically significantly greater reductions in PANSS total score [treatment differences: -8.72 and -7.64, respectively] and CGI severity score [treatment differences: -0.33 and -0.38]. The most common treatment-emergent adverse event for brexpiprazole was akathisia [2 mg: 4.4%; 4 mg: 7.2%; placebo: 2.2%]. Weight gain with brexpiprazole was moderate [1.45 and 1.28 kg for 2 and 4 mg, respectively, versus 0.42 kg for placebo at week 6]. There were no clinically or statistically significant changes from baseline in lipid and glucose levels and extrapyramidal symptom ratings.

CONCLUSIONS: Brexpiprazole at dosages of 2 and 4 mg/day demonstrated statistically significant efficacy compared with placebo and good tolerability for patients with an acute schizophrenia exacerbation.

First off, in the

PsychiatricNews article above, the comment "

Researchers from the Department of" isn’t accurate. It should read "

A researcher from the Department of" since all the other authors on the by-line are employees of either Lundbeck or Otsuka [in

blue].The PHARMA companies seem to have dropped the multiple academics on the by-line method and settled for only one.

Dr. Christoph Correll made the following COI declaration:

Dr. Correll has been a consultant and/or advisor to or has received honoraria from Actelion, Alexza, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon, Eli Lilly, Genentech, Gerson Lehrman Group, IntraCellular Therapies, Lundbeck, Medavante, Medscape, Merck, National Institute of Mental Health, Janssen/J&J, Otsuka, Pfizer, ProPhase, Roche, Sunovion, Takeda, Teva, and Vanda; he has received grant support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, Janssen/J&J, National Institute of Mental Health, NARSAD, and Otsuka; and he has been a Data Safety Monitoring Board member for Cephalon, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Lundbeck, Pfizer, Takeda, and Teva.

And did he [they] have any help writing the paper?

Funded by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc., and H. Lundbeck A/S. Jennifer Stewart, M.Sc. [QXV Communications, Maccles field, U.K.] provided writing support that was funded by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc., and H. Lundbeck A/S.

So far, we’re not getting a lot of reform-is-in-the-air vibes. How about the other paper that’s part of the FDA NDA submission?

by Kane JM, Skuban, Ouyang, Hobart, Pfister, McQuade, Nyilas, Carson, Sanchez, and Eriksson.

Schizophrenia Research. 2015 Feb 12. [Epub ahead of print]

The objective of this study was to evaluate the efficacy, safety and tolerability of brexpiprazole versus placebo in adults with acute schizophrenia. This was a 6-week, multicenter, placebo-controlled double-blind phase 3 study. Patients with acute schizophrenia were randomized to brexpiprazole 1, 2 or 4mg, or placebo [2:3:3:3] once daily. The primary endpoint was changed from baseline at week 6 in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale [PANSS] total score; the key secondary endpoint was Clinical Global Impressions-Severity [CGI-S] at week 6. Brexpiprazole 4mg showed statistically significant improvement versus placebo [treatment difference: -6.47, p=0.0022] for the primary endpoint. Improvement compared with placebo was also seen for the key secondary endpoint [treatment difference: -0.38, p=0.0015], and on multiple secondary efficacy outcomes. Brexpiprazole 1 and 2mg also showed numerical improvements versus placebo, although p>0.05. The most common treatment-emergent adverse events were headache, insomnia and agitation; incidences of akathisia were lower in the brexpiprazole treatment groups [4.2%-6.5%] versus placebo [7.1%]. Brexpiprazole treatment was associated with moderate weight gain at week 6 [1.23-1.89kg versus 0.35kg for placebo]; there were no clinically relevant changes in laboratory parameters and vital signs. In conclusion, brexpiprazole 4mg is an efficacious and well-tolerated treatment for acute schizophrenia in adults… BEACON trial.

[recolored to match the graph above]

[recolored to match the graph above]

Again, there is only one academic author,

Dr. John Kane, with the following COI declaration:

Dr Kane has been a consultant for Amgen, Alkermes, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Eli Lilly, EnVivo Pharmaceuticals [Forum] Genentech, H. Lundbeck. Intracellular Therapeutics, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Johnson and Johnson, Merck, Novartis, Otsuka, Pierre Fabre, Proteus, Reviva, Roche and Sunovion. Dr Kane has been on the Speakers Bureaus for Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Genentech and Otsuka, and is a shareholder in MedAvante, Inc.

Writing help?

Ruth Steer, PhD, [QXV Communications, Macclesfield, UK] provided writing support, which was funded by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. [Princeton, USA] and H. Lundbeck A/S [Valby, Denmark].

Does QXV Communications sound familiar? And speaking of sounding familiar, in case you didn’t follow the author links, Dr. John Kane is Chairman of Psychiatry at Hofstra where Dr. Christoph Correll is on the faculty [it was

one·stop shopping for both

ghost·writers and

KOLs]. Both authors are at the

Feinstein Institute for Medical Research. Both articles say:

From the Zucker Hillside Hospital, Glen Oaks, N.Y.; Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Princeton, N.J.; and H. Lundbeck A/S, Valby, Copenhagen, Denmark.

I know this is getting long, but let me add one other tidbit. The top article referenced a 2013 meta-analysis in the Lancet [

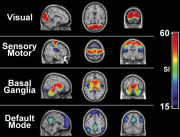

Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis] of the Effect Sizes and Discontinuation Rates of the Atypical Antipsychotics which I liked, by authors who do Cochrane meta-analyses. I lifted one of their figures and added the results from these Brexpiprazole studies for comparison. The Effect Size is an index of the magnitude of the drug’s effect. It was included in the AJP article but not the Schizophrenia Research article [I didn’t calculate the 95% Confidence Limits for the Brexpiprazole studies]. It shows a problem in replicability [2mg]:

First, I apologize for going on and on about this. When I started, I had no intention of writing a

blog·epic. I didn’t know that the academic authors were from the same department; or that the

ghost·writers were from the same firm; or that they were ignoring the Clinicaltrials.gov Results Database; or that there were 60 sites for each study. I guess they are taking advantage of the formula used by their predecessors to maximize their impact on launch with slick writing and optimized choices in data presentation. If you read the actual papers, they even read like advertisements. They’re obviously going to be handout reprints for the drug reps to give out to primary care physicians. They are in some of the top journals, quickly published after submission, and presented together as a poster at the

American College of Neuropsychopharmacology [ACNP] meeting in December.

I just wrote a three part series on the Academic·Industrial·Complex that was as overly detailed as this post – which is yet another example of what that phrase means. I think I’ve been chasing down the details, looking in vain for something that breaks out of the mold of scientific enterprise being used as a commercially driven advertising platform. And what I find is that the further I look, the worse it gets. I was tempted to say that Brexpiprazole is a weak sister Atypical Antipsychotic with a low Adverse Event profile, but I’m not even sure that’s defensible with just two six week trials. And unmentioned here, they used some idiosyncratic analytic techniques that were unfamiliar to me, but I just didn’t have the libido to look into them further [because there was no primary data to test them with].

This is pitiful, in my humble opinion. We’ve clearly still got a long way to go to reclaim our academic literature, in spite of the good news coming from various directions…

Afterthought: Looking at all of those sites on the two clinical trials, it is highly unlikely that any author ever even met a single subject in either trial…

Another Afterthought: They could call Brexpiprazole son of Abilify…

Otsuka Pharmaceuticals was dealt a setback yesterday when the FDA approved four generic versions of its best-selling Abilify® antipsychotic pill, following an unusual and protracted legal battle. Shortly thereafter, Teva Pharmaceuticals announced that it was launching a copycat medicine. The move comes after Otsuka cited complex regulatory law to thwart generics, but the agency rejected the argument and decided that generic versions meet the standard for approval… And Otsuka also has a great deal at stake – Abilify® generated $4.9 billion in U.S. sales last year.

was actually attempting to usher in generic copies.

For its part, the FDA backpedaled and earlier this month told Otsuka that Abilify® was now approved to treat Tourette syndrome, but only for children. However, the agency also indicated it may use a so-called carve-out approach to approve generics for treating psychiatric disorders, but not Tourette syndrome. And that is what the FDA did Tuesday…

Guest Authors: In this case, the articles are no longer crammed with academics like a decade ago. I guess it only takes one to be the ticket into an academic journal. In this case, the main authors came from

Guest Authors: In this case, the articles are no longer crammed with academics like a decade ago. I guess it only takes one to be the ticket into an academic journal. In this case, the main authors came from  Well, this can’t be a book review of Lieberman’s and Ogasi’s

Well, this can’t be a book review of Lieberman’s and Ogasi’s  [This is a rough stab at introducing their methodology from one boring old psychoanalyst – so be gentle]. 25 years ago,

[This is a rough stab at introducing their methodology from one boring old psychoanalyst – so be gentle]. 25 years ago,  What

What

to forget how much money is involved in the commerce of these drugs. Abilify® is currently involved in a similar

to forget how much money is involved in the commerce of these drugs. Abilify® is currently involved in a similar  But whether my speculations are true or not, Drs. Elliot and Turner have opened a window into the world of psychiatry’s Clinical Trials and the whole Academic·Industrial·Complex that goes much further than the tragic case of Dan Markingson, than the Department of Psychiatry, than the State of Minnesota. We need even more than just the Data Transparency we’re seeking. We need Transparency for the whole Clinical Trial process. While I’m personally sensitive to the problem of financing psychiatric education, an area I left reluctantly – no matter what problems the Academic·Industrial·Complex tried to fix, it didn’t justify the obvious lapses in medical ethics that arose out of the solution. Faustian contracts with the Devil rarely do…

But whether my speculations are true or not, Drs. Elliot and Turner have opened a window into the world of psychiatry’s Clinical Trials and the whole Academic·Industrial·Complex that goes much further than the tragic case of Dan Markingson, than the Department of Psychiatry, than the State of Minnesota. We need even more than just the Data Transparency we’re seeking. We need Transparency for the whole Clinical Trial process. While I’m personally sensitive to the problem of financing psychiatric education, an area I left reluctantly – no matter what problems the Academic·Industrial·Complex tried to fix, it didn’t justify the obvious lapses in medical ethics that arose out of the solution. Faustian contracts with the Devil rarely do…  [see

[see