Posted on Tuesday 7 April 2015

An explanatory randomised controlled trial testing the effects of targeting worry in patients with persistent persecutory delusions: the Worry Intervention Trial [WIT].Editors: Freeman D, Dunn G, Startup H, and Kingdon DLancet. 2015 2[4]:305-313.NCBI Bookshelf: Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015.

BACKGROUND: Persecutory delusions are a key experience in psychosis, at the severe end of a paranoia continuum in the population. Treatments require significant improvement. Our approach is to translate recent advances in understanding delusions into efficacious treatment. In our research we have found to be an important factor in the occurrence of persecutory delusions. Worry brings implausible ideas to mind, keeps them there and makes the experience distressing. Reducing worry should lead to reductions in persecutory delusions.OBJECTIVE: The objective was to test the clinical efficacy of a brief cognitive–behavioural intervention for worry for patients with persistent persecutory delusions and determine how the treatment might reduce delusions. Embedded within the trial were theoretical studies to improve the understanding of worry in psychosis…MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES: The main outcomes measures were of worry [Penn State Worry Questionnaire; PSWQ] and persecutory delusions [Psychotic Symptom Rating Scales; PSYRATS]. Secondary outcome measures were paranoia, overall psychiatric symptoms, psychological well-being, rumination and a patient-chosen outcome.RESULTS: In total, 95% of the patients provided primary outcome follow-up data. For the primary outcomes, in an intention-to-treat analysis, when compared with treatment as usual, the therapy led to highly significant reductions in both worry [PSWQ: 6.35, 95% confidence interval [CI] 3.30 to 9.40; p < 0.001] and the persecutory delusions [PSYRATS: 2.08, 95% CI 0.64 to 3.51; p = 0.005]. The intervention also led to significant improvements in all of the secondary outcomes. All gains were maintained. A planned mediation analysis indicated that change in worry explained 66% of the change in the delusions. We also found that patients without intervention report a passive relationship with worry, feeling unable to do anything about it; worry brings on depersonalisation experiences; and the patient group has very low levels of psychological well-being.CONCLUSIONS: This was the first large randomised controlled trial specifically focused on the treatment of persecutory delusions. Long-standing delusions were significantly reduced by a brief CBT intervention targeted at worry. The intervention also improved well-being and overall levels of psychiatric problems. An evaluation of the intervention in routine clinical setting is now indicated. We envisage developing the intervention booklets for online and app delivery so that the intervention, with health professional support, has the possibility for greater self-management.

Daniel Freeman and colleagues report the results from thei r trial that investigated the clinical effects of an intervention targeting worry in patients with non-affective psychosis. The authors accurately write in their Introduction that treatments for psychotic conditions, such as schizophrenia, need substantial improvement. The first-line treatment of schizophrenia—ie, antipsychotics—can suppress delusions and hallucinations, but patients still suffer from other symptoms such as negative symptoms, and often report adverse side-effects from the medication [eg, apathy, neurological side-effects, serious weight gain, and sexual dysfunction]. The percentage of non-compliance with medication in patients with schizophrenia is as high as 40–50%, and 74% of patients discontinue their medication within 18 months. Furthermore, Wunderink and colleagues report that dose reduction or discontinuation of antipsychotics during the early stages of remitted first-episode psychosis is associated with superior long-term [7 years] recovery rates [40·4%] compared with the rates achieved with antipsychotic maintenance treatment [17·6%]. Additionally, Morrison and colleagues reported that cognitive therapy significantly reduced psychiatric symptoms and seems to be a safe and acceptable alternative for people with schizophrenia and related disorders who have chosen not to take antipsychotic medication. In consideration of low patient compliance with antipsychotics, evidence for improved long-term functional recovery with dose reduction or discontinuation of antipsychotic medication, and the promising results from trials of psychological treatments, intervention options for patients with a psychotic disorder are clearly needed that are effective, have fewer side-effects, and are more acceptable to some patients than antipsychotics.

11.1.1 Effectiveness of cognitive behaviour therapy There is a consistent evidence base suggesting that many people find CBTp helpful. Other forms of therapy can also be helpful, but so far it is CBTp that has been most intensively researched. There have now been several meta-analyses [studies using a statistical technique that allows findings from various trials to be averaged out] looking at its effectiveness. Although they each yield slightly different estimates, there is general consensus that on average, people gain around as much benefit from CBT as they do from taking psychiatric medication…The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE] considers the evidence strong enough to recommend that everyone with a diagnosis of schizophrenia should be offered CBT. NICE recommends that people should be offered at least 16 one-to-one sessions over a minimum of six months. However, this is far from being the case everywhere: indeed the Schizophrenia Commission found that only one in ten people who could benefit from it have access to good CBTp. We view this with grave concern – indeed, it has been described as scandalous…

11.10 Conclusions There is now overwhelming evidence that psychological approaches can be very helpful for people who experience psychosis. However, there remains a wide variation in what is available in different places. Even the most successful approaches, such as early intervention and family work, are often not available, and nine out of ten of those who could benefit have no access to CBT. There is a pressing need for all services to come up to the standard of the best and to offer people genuine choices. Perhaps most importantly, we need a culture change in services such that the psychological understanding described in this report informs every conversation and every decision…

There was the phenomenal work of Anthony Morrison, who is the first researcher to empirically show that psychotherapy can be effective with individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia, even when they choose to not take psychotropics. Although many know this intuitively, the scientific community is not really interested in intuition; for him to show this repeatedly through empirical data is profound.

Posted on Monday 6 April 2015

A few weeks ago, I was commenting on an article in JAMA:Psychiatry by three Residency Training Directors [yellow brick roads…] who were advocating a curriculum for psychiatry residents in neuroscience [The Future of Psychiatry as Clinical Neuroscience: Why Not Now?]. The gist of the article had to do with preparing future psychiatrists for the expected breakthroughs coming in neuroscience. Going so far as to say…

The overarching goal is that residents will incorporate a modern neuroscience perspective as a core component of every formulation and treatment plan and bring the bench to the bedside.

…which I thought sounded like something the USSR of old might have come up with back in the days before the walls fell down. I recalled a graphic I came up with four years ago about Tom Insel’s campaign for clinical neuroscience. I made it from an old Red Army poster from the days of the Russian Revolution, so I guess that I’ve thought of that analogy before. The constant hype about Neuroscience has been like the seven decades of Russian Communism, hope was always in the future [a future that ever came]. Note also the allusion to the Translational Medicine metaphor – another NIMH favorite [moving research findings rapidly from "the bench to the bedside"]. Best I can tell, we’ve established a network of Translational Centers all decked out for service, but there’s been nothing of note to translate.

…which I thought sounded like something the USSR of old might have come up with back in the days before the walls fell down. I recalled a graphic I came up with four years ago about Tom Insel’s campaign for clinical neuroscience. I made it from an old Red Army poster from the days of the Russian Revolution, so I guess that I’ve thought of that analogy before. The constant hype about Neuroscience has been like the seven decades of Russian Communism, hope was always in the future [a future that ever came]. Note also the allusion to the Translational Medicine metaphor – another NIMH favorite [moving research findings rapidly from "the bench to the bedside"]. Best I can tell, we’ve established a network of Translational Centers all decked out for service, but there’s been nothing of note to translate.

Rather than being "ready to embrace new findings as they emerge", tomorrow’s psychiatrist needs to know how to critically evaluate new findings as they emerge.

I remember being taught as a resident about Broadmann Area 25 being critical in the pathogenesis of depression, based on exciting initial deep brain stimulation results from Dr. Helen Mayberg. This was almost treated as an established fact, despite the very preliminary nature of the research. Well, what happened when they tried to do a larger clinical trial? Neurocritic reported that the trial was halted before its planned endpoint in December 2013, and last month it was revealed that the medical device company conducting the trial [St. Jude] stopped it due to perceived study futility.

"All of the neurons together in one brain form more connections with each other than there are stars and planets in the galaxy." The professor ended his lecture by giving us some practical tips based on his knowledge of neuroscience. Time and repetition, he told us, is what will help us succeed in the class, because that is how neuronal circuits are programmed and how processes in the brain ranging from retrieving facts from memory to riding a bicycle become automatic. I use the same advice almost daily with my patients when I emphasize to them the importance of practicing new behaviors or ways of dealing with difficult thoughts and emotions. Similarly, based on my reading of research on the effects of sleep, exercise, and social interactions on the brain, I share with my patients the importance of getting enough of each.

… the narrow view tends to emphasize things like genetics, neurotransmitters, biomarkers, and circuits.

Posted on Saturday 4 April 2015

Authors’ replyOur trial was not designed to change clinical practice. It was a preliminary trial, which needs to be followed up by a larger, pragmatic multicentre study. It is important not to over·interpret our data, and we explicitly advised against discontinuation of medication. We claimed the trial showed that cognitive therapy was safe and acceptable, not safe and effective…

INTERPRETATION: Cognitive therapy significantly reduced psychiatric symptoms and seems to be a safe and acceptable alternative for people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders who have chosen not to take antipsychotic drugs.

by A. P. Morrison, P. Hutton, M. Wardle, H. Spencer, S. Barratt A. Brabban, P. Callcott, T. Christodoulides, R. Dudley, P. French, V. Lumley, S. J. Tai and D. TurkingtonPsychological Medicine. 2012 42[05]:1049-1056.

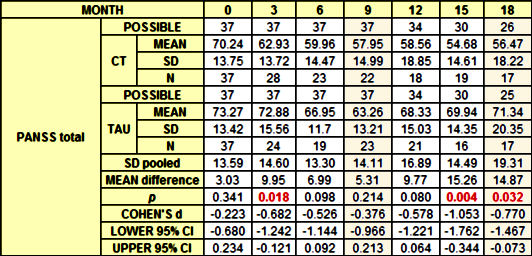

Background Although antipsychotic medication is the first line of treatment for schizophrenia, many service users choose to refuse or discontinue their pharmacological treatment. Cognitive therapy (CT) has been shown to be effective when delivered in combination with antipsychotic medication, but has yet to be formally evaluated in its absence. This study evaluates CT for people with psychotic disorders who have not been taking antipsychotic medication for at least 6 months.Method Twenty participants with schizophrenia spectrum disorders received CT in an open trial. Our primary outcome was psychiatric symptoms measured using the Positive and Negative Syndromes Scale [PANSS], which was administered at baseline, 9 months [end of treatment] and 15 months [follow-up]. Secondary outcomes were dimensions of hallucinations and delusions, self-rated recovery and social functioning.Results T tests and Wilcoxon’s signed ranks tests revealed significant beneficial effects on all primary and secondary outcomes at end of treatmentand follow-up, with the exception of self-rated recovery at end of treatment. Cohen’s d effect sizes were moderate to large [for PANSS total, d=0.85, 95% CI 0.32–1.35 at end of treatment; d=1.26, 95% CI 0.66–1.84 at follow-up]. A response rate analysis found that 35% and 50% of participants achieved at least a 50% reduction in PANSS total scores by end of therapy and follow-up respectively. No patients deteriorated significantly.

Conclusions This study provides preliminary evidence that CT is an acceptable and effective treatment for people with psychosis who choose not to take antipsychotic medication. An adequately powered randomized controlled trial is warranted.

Conclusions This study provides preliminary evidence that CT is an acceptable and effective treatment for people with psychosis who choose not to take antipsychotic medication. An adequately powered randomized controlled trial is warranted.

Posted on Thursday 2 April 2015

Living in the UK in the1970s practicing in an a US Air Force Hospital near one of the UK’s primo Hospitals [Addenbrooks, in Cambridge] was interesting. Suffice it to say that our systems and expectations are very different. I never quite ‘got it‘ – except to say ‘very different‘ and ‘interesting.’ I think I understand the term, ‘service users‘ in the papers I’m about to discuss. It means, ‘people who rely on the National Health Service‘ for their health care – according to Wikipedia, that’s 92%. If I understand correctly, NICE [National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence] sets treatment guidelines one of which is to offer CBT [16 sessions] to service users with Schizophrenia, but it’s not really available through the NHS. That adds a commercial element to the issues brought up by the BPS report [or I could’ve misread the whole thing].

There was the phenomenal work of Anthony Morrison, who is the first researcher to empirically show that psychotherapy can be effective with individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia, even when they choose to not take psychotropics. Although many know this intuitively, the scientific community is not really interested in intuition; for him to show this repeatedly through empirical data is profound.

by Morrison AP, Turkington D, Pyle M, Spencer H, Brabban A, Dunn G, Christodoulides T, Dudley R, Chapman N, Callcott P, Grace T, Lumley V, Drage L, Tully S, Irving K, Cummings A, Byrne R, Davies LM, and Hutton P.Lancet. 383[9926]:1395–1403

BACKGROUND: Antipsychotic drugs are usually the first line of treatment for schizophrenia; however, many patients refuse or discontinue their pharmacological treatment. We aimed to establish whether cognitive therapy was effective in reducing psychiatric symptoms in people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders who had chosen not to take antipsychotic drugs.METHODS: We did a single-blind randomised controlled trial at two UK centres between Feb 15, 2010, and May 30, 2013. Participants aged 16-65 years with schizophrenia spectrum disorders, who had chosen not to take antipsychotic drugs for psychosis, were randomly assigned [1:1], by a computerised system with permuted block sizes of four or six, to receive cognitive therapy plus treatment as usual, or treatment as usual alone. Randomisation was stratified by study site. Outcome assessors were masked to group allocation. Our primary outcome was total score on the positive and negative syndrome scale [PANSS], which we assessed at baseline, and at months 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, and 18. Analysis was by intention to treat, with an ANCOVA model adjusted for site, age, sex, and baseline symptoms. This study is registered as an International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial, number 29607432.FINDINGS: 74 individuals were randomly assigned to receive either cognitive therapy plus treatment as usual [n=37], or treatment as usual alone [n=37]. Mean PANSS total scores were consistently lower in the cognitive therapy group than in the treatment as usual group, with an estimated between-group effect size of -6.52 [95% CI -10.79 to -2.25; p=0.003]. We recorded eight serious adverse events: two in patients in the cognitive therapy group [one attempted overdose and one patient presenting risk to others, both after therapy], and six in those in the treatment as usual group [two deaths, both of which were deemed unrelated to trial participation or mental health; three compulsory admissions to hospital for treatment under the mental health act; and one attempted overdose].INTERPRETATION: Cognitive therapy significantly reduced psychiatric symptoms and seems to be a safe and acceptable alternative for people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders who have chosen not to take antipsychotic drugs. Evidence-based treatments should be available to these individuals. A larger, definitive trial is needed.

Participants allocated to cognitive therapy received a mean of 13.3 sessions [SD 7.57; range 2–26], with each session lasting roughly 1 h [these figures do not include the four booster sessions that were available]. Adherence to cognitive therapy was reasonably good, with no patients not attending any sessions, and 30 [82%] having at least six or more sessions.

… 74 individuals were randomised to the cognitive therapy plus treatment as usual group [n=37], or the treatment as usual alone group [n=37]. We stopped before the target of 80 individuals in accordance with our recruitment timeline, on the basis of restricted resources, to ensure that we had the possibility to obtain 9 month data for all participants. Baseline characteristics were similar between groups.

By examination of the proportion of participants achieving good clinical outcomes in each disorder [defined by use of an improvement of >50% in adjusted PANSS total scores], we noted that, at 9 months, seven [32%] of 22 participants in the cognitive therapy group, and three [13%] of 23 from the treatment as usual group had achieved good clinical outcomes. At 18 months seven [41%] of 17 receiving cognitive therapy and three [18%] of 17 receiving treatment as usual had achieved good clinical outcomes.

With regards to use of antipsychotic drugs throughout the lifetime of the trial, ten [4%] of 37 participants in the cognitive therapy group were prescribed antipsychotics after randomisation [eight during the treatment window and two during the follow-up phase] as were ten [4%] of 37 in the treatment as usual group [nine during the treatment window and one during the follow-up phase].

So in-so-far as I’m able to vet this study, I would see it as a pilot project showing a signal that deserves repeating, but I can’t confirm the opening quote above, the article’s conclusion, or the commentary on the article. Here’s the thing of it, my bias is on the side of confirmation. I support psychotherapeutic intervention in Schizophrenia. I’m not sure I would’ve picked CBT, but I’m not an CBT-er, and from what I can read, Morrison et al have adapted the technique to be used in this condition.

Posted on Monday 30 March 2015

There are likely to be a number of features to the current debate.

First an impression will be created that we know more about these drugs than we in fact do.We know almost nothing about what antidepressants actually do – we still don’t know what they do to serotonin. Rather than being effective like an antibiotic, these drugs have effects – as alcohol does. Their primary effect is to emotionally numb. Patients on them walk a tightrope as to whether this emotional effect is going to be beneficial or disastrous.

Posted on Monday 30 March 2015

Sometimes, frustration and impossibility are necessary components of learning. Try looking around on the Internet for something that captures the essence of the difference between legal and ethical, between the Rule[s] of Law and a Code of Ethics. There’s plenty to find, sure enough, but something about the last thing I found isn’t quite it, so I return to the search. As in the phrase, the letter of the Law, Laws cover a minimal definable and enforceable standard of behavior derived from Ethics, which are more felt than written, more the difference between wrong and not right. So it’s little wonder that the Case of Dan Markingson is finally being decided by a faculty senate, a panel from an accrediting agency, and a legislative body, instead of in a Court of Law. Equally telling, it has become a cause célèbre through the efforts of an academic department of bioethics.

It’s hard to imagine reading the details of Dan’s story without seeing how not right it was from day one to its tragic ending. In the narratives of most other problematic Clinical Trials, the misrepresented efficacy or de-emphasized patient harms are experience distant from the trial itself, showing up as impersonal statistics from later users of the drug. In this case, it was the conduct of the trial itself that did the damage, not just some mathematical trick in the analysis or sleight of hand in the presentation of the study’s outcome. This case is also unique in that the role of the particular academic institution involved is central to the publicity – the Department of Psychiatry, the Institutional Review Board, the Clinical Research Center, and the Administration at the University of Minnesota. And this story is populated – Charles Schultz, Stephen Olson, Eric Kaler, Dan Markingson, Mary Weiss, Carl Elliot, Leigh Turner, Mike Howard – actual people make the story more real. And of course, the fact that Dan killed himself in an altered state [making sense…] some six months after he was placed in this Clinical Trial is an indelible marker of its not rightness – un·ethical.

-

When his mother visited him in California June 2003, he was floridly delusional, yet was still able to convince the police that he was fine [see The Deadly Corruption of Clinical Trials].

-

His September emails were again quite delusional, as was his presentation in Minnesota in November. But again, after 12 days on Risperdal®, he seemed to have cleared [see Study Visits p. 5], passing of his former symptoms as "lack of sleep." yet, whistleblower Nikki Gjere said that he was "too sick to be in the study" at that time [a paradigm…., INVESTIGATORS: Nurse questions integrity of U of M drug researchers].

-

Notes from various sources and Dan’s journal suggest that for the last several months of his life, he was getting worse [making sense…]. From the journal:Mar 23, 2004: "world walking, you were at a farm house and we’re getting presents from dogs who had presents fastened in plastic bags to their snouts… in the gloaming and breening, you were thinking of naming it gloaming and greening or gloam-green. That was someone brings a snowslide in summer or midsummer. It has been left behind…" [Olson 2007 p. 467].But from what I can find, it certainly appears that Dan was very ill either on-and-off or throughout the study.

Posted on Saturday 28 March 2015

NIMHby Tom Insel03/26/2015… This update of our Strategic Plan is a commitment to take a fresh look at our horizons so that we can refine priorities and energize our path of discovery.

We know that some scientists reject the concept of “directed science,” believing that science rarely follows a plan. True, important discoveries often result from serendipity or side roads rather than a premeditated, carefully articulated strategy. On the other hand…

While the tools of genomics and neuroscience now permit rapid progress, equivalent tools and paradigms to study environmental influences are just being developed. Over this next 5-year period, we can expect this new approach to environmental factors, sometimes called the exposome, to yield more scientific traction in understanding the mechanisms by which environmental factors alter brain and behavior, from prenatal development through the process of aging…

To unravel the mechanisms that lead to mental illnesses and target novel treatments to those mechanisms, more comprehensive descriptions of the molecules, cells, and circuits associated with typical and atypical behavior are necessary. What classes of neurons and glia are involved in a given aspect of mental function? Which brain regions contribute to a single thought or action, and how are these regions interconnected? These questions will be answered by defining the cellular components of circuits, including their molecular properties and anatomical connections. New tools and techniques that span biological scales—from single-cell analysis, to macro-electrode arrays, to systems-level brain imaging — are needed to address these questions.

Pushing that simple analogy, many critics would go further and say that it’s all software [as in the BPS Report Understanding Psychosis and Schizophrenia] or Schizophrenia: a critical psychiatry perspective] taking the psycho·social·perspective to extremes, saying that mainstream psychiatry is totally at sea in its hardware bio·perspective. But as much as I enjoy reading about the neuroscience, my take on Insel’s NIMH 2015 Strategic Plan is that it’s wildly speculative, making fantasmagoric extrapolations that move way, way beyond the frontiers of anything we know [but then again, I felt something similar in the other direction about the those psycho·social articles].

NIMH: Director’s Blogby Thomas InselJanuary 26, 2012NIMH, like all Institutes at NIH, has an advisory council that meets three times each year. The National Advisory Mental Health Council [NAMHC] is a distinguished group of scientists, advocates, clinicians, and policy experts. Each of our meetings includes a closed session to review individual grants considered for funding and a session open to the public that engages this diverse group in discussions about the larger issues that guide NIMH funding.

At last week’s session, we heard a recurrent tension around one such larger issue. Some members of Council bear witness to the poor quality of care, the unmet medical need, and the diminishing investments by states on behalf of people with mental disorders. They reasonably ask, “How are we ensuring that the science that NIMH has produced is implemented where the need is greatest?” They also question on the pay-off of genetics research. After all, two decades after the gene for Huntington’s disease was identified, we still have no effective treatments, and Huntington’s disease is genetically far simpler than schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. In contrast to so many neurological diseases, we have effective treatments for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. NIMH should be investing to ensure these are available.

The opposing argument runs something like this. There has been no major innovation in therapeutics for most mental disorders since 1960. Current treatments are not good enough for too many. Rather than investing scarce dollars for incremental improvements or increased dissemination of mediocre interventions, we need invest in the fundamental science of brain and behavior so that we can understand how to develop better treatments…

Sixty years ago, the nation faced a similar short-term vs. long-term debate about polio. The needs were growing and the causes were unknown. Some wanted funds invested only in better services, including improved iron lungs. Others argued for investing in a vaccine with a long-term goal of eradication. As David Oshinsky explains in his outstanding retelling of this debate, the government went with the services approach, leaving advocates and families to raise funds for vaccine development. Let us hope we don’t short-change our grandchildren, sixty years from today, by failing to invest in the long-term promise of more effective diagnostics and therapeutics for mental disorders.

Posted on Friday 27 March 2015

-

Recently, I mentioned the first case assigned to me as a psychiatry resident, a woman I called Gloria [back to the drawing board…] who was hospitalized awaiting a transfer to a long term facility as a NGRI [Not Guilty by Reason of Insanity] case after drowning her son during a psychotic episode. I came to my residency after a tour of duty in an overseas Air Force hospital where I was an Internist. When I decided to change specialties, while still there, I read everything I could get my hands on about psychiatry. There was a copy of Eugen Bleuler’s 1911 Dementia Praecox or the Group of Schizophrenias in the hospital library, and I read it from cover to cover. Why it was in the small library of our small hospital in rural England is unknown to me. But I was taken with his description of the premorbid personality of patients who went on to develop Schizophrenic illnesses, and what he called the Primary Symptoms [the four As: loosened Association of thought, inappropriate Affect, global Ambivalence, and Autism – private logic]. I also read the Psychiatry Textbook of the day, Friedman and Kaplan, that had a detailed discussion of the "psychotic break" in the Schizophrenic patient. In back to the drawing board…, I mentioned a conversation with Gloria’s mother, but that was only one of several. Her mother came at every visiting time, and would often catch me and talk about her daughter. It seemed to help her tell the story, and I was more than happy to listen. She described her daughter exactly as Bleuler and the text I had read – schizoid features in her persona, periodic temper outbursts, a long period of seeming confusion prior to "the break." I was amazed at the concordance of her description and Bleuler’s century-old writings.

-

A few years ago, I described a case I saw not long after finishing my residency [see 1. from n equals one…, 2. from n equals one…, etc]. She was hospitalized after she had been stopped from jumping from the 14th floor of the atrium in a downtown hotel. I was the fourth psychiatrist to see her and none of us quite knew what was going on. From my previous post:She was confused. My friend was confused. So was I. She didn’t seem depressed and had no explanation for her behavior. At the time I saw her, she was completely focused on getting out of the hospital because she didn’t want to be a financial burden on her parents. It was over thirty years ago, but I recall the interview clearly. She was coherent with no signs of psychosis. She was ill-suited and untrained for her job, but mainly felt she’d failed her parents who had been instrumental in getting it through a friend at the bank. She had no explanation for her behavior. What I mainly recall from the interview was that she tried very hard to answer every question I asked her, but looked at me oddly, as if to say, "Why are you asking that?" I saw her several times, still feeling somewhat lost. By this time, the pressure to leave the hospital had escalated and they set up a plan. She would go home to her parents house, take a leave from her job, and see both my friend and I as an outpatient. Once home, she refused both options, or to take any medicine, or to see anyone else. She told her parents that she would see me in the future, when she’d "sorted things out."I had a hunch that this was the prodrome to a schizophrenic break based on her history, presentation [and reading Bleuler]. She had already been tried on an antipsychotic with no effect. I saw her parents as something as an advisor while she lived at home, obviously uncomfortable but steadfast in her resolve to sort things out by herself. Then one day, she asked to see me, appearing in my waiting room that afternoon in a psychotic state and was admitted for the first of several hospitalizations. I followed her at varying intervals until I retired some twenty plus years later.

-

In the recent weeks, we’ve finally seen the case of Dan Markingson being definitively dealt with [from Minnesota: Dan Markingson revealed…, ethics…, making sense…]. In making sense…, I was discussing the last several moths of his life. He was apparently not overtly psychotic. There’s no mention of hallucinations or the bizarre delusions that had been apparent in the earlier period of his illness. But he was not doing well at all. There are indicators from most of the venues where he was seen and his own journal that he was decompensating without the psychotic symptoms he’d had on admission – instead he had the "Primary Symptoms" as described by Bleuler.

Posted on Thursday 26 March 2015

Current Opinion – Reviewby Joanna Moncrieff and Hugh Middleton2015

Purpose of review The term ‘schizophrenia’ has been hotly contested over recent years. The current review explores the meanings of the term, whether it is valid and helpful and how alternative conceptions of severe mental disturbance would shape clinical practice.Recent findings Schizophrenia is a label that implies the presence of a biological disease, but no specific bodily disorder has been demonstrated, and the language of ‘illness’ and ‘disease’ is ill-suited to the complexities of mental health problems. Neither does the concept of schizophrenia delineate a group of people with similar patterns of behaviour and outcome trajectories. This is not to deny that some people show disordered speech and behaviour and associated mental suffering, but more generic terms, such as ‘psychosis’ or just ‘madness’, would be preferable because they are less strongly associated with the disease model, and enable the uniqueness of each individual’s situation to be recognized.Summary The disease model implicit in current conceptions of schizophrenia obscures the underlying functions of the mental health system: the care and containment of people who behave in distressing and disturbing ways. A new social framework is required that makes mental health services transparent, fair and open to democratic scrutiny.

I came to psychiatry from a career in Internal Medicine [formerly known as Diagnosticians]. And my first encounter [in my life] with the phrase medical model of disease or the idea that a diagnosis implied biological causation came from a fellow first year psychiatry resident [whose copy of Szasz’s The Myth of Mental Illness was always within arms reach – see Szasz by proxy…]. The idea that disease was certified by objective biosignatures was foreign to me. So I read Szasz’s books and I think I gained some things by pondering the questions he raised, but his were forced arguments to me. Diagnosis didn’t lead to cause for me in either career – it lead to action, to treatment. If I were a surgeon at the Battle of Gettysburg and you were brought to me with a gunshot wound to the leg, I sawed your leg off. It wasn’t because I knew anything about infection. During our Civil War, Louis Pasteur was still studying wine-making [it was well after Appomattox when he came up with his germ theory of disease]. I sawed off your leg because I knew you’d die if I didn’t.

And as a Rheumatologist in that former life, there were only a few lab tests that helped at times, but the main guideposts for treatment and prognosis came from careful clinical diagnosis. So although like Moncrieff and Middleton, I can see that psychiatric diagnosis has been jury-rigged to imply biological causality by too many people in high places, I see that as a perversion of the meaning of medical diagnosis – something that needs to be fixed and clarified.

And agreeing with the problem they describe doesn’t lead me to necessarily agree with their solution. If they were talking about the DSM-III-IV-5 category Major Depressive Disorder, I’d jump on the train in a blue second. But I’m balking at following along with Schizophrenia. One reason for my hesitation is that their reason to jettison the diagnosis relies heavily on their aversion to the implications of the diagnosis – implications imputed there without solid scientific back-up, as perversions of the traditional meanings and uses of medical diagnosis. It’s a reaction against something. I felt the same way about the BPS Report [Understanding Psychosis and Schizophrenia] which was also driven by a reaction against that same something [see <to be continued>…, back to the drawing board…]. That’s what Dr. Spitzer’s DSM-III did, reacted so strongly against something that the result was the creation of some big problems [this one included] that we still deal with some thirty-five years later. Likewise, Moncrieff and Middleton clearly have some «alternative conceptions of severe mental disturbance» that remain as speculative as those of their biologically inclined counterparts.