Posted on Sunday 2 March 2014

In musings…, the thing I was musing about wasn’t, apparently, clearly stated based on some emails and tweets that came my way. Here’s another shot. I work as a volunteer in a local charity clinic. There are several reasons, but one of the main ones is that the local primary care physicians and my colleagues in the clinic don’t know much about psychiatric medications and treat them as if they are like the symptomatic medications in the rest of medicine. So if a person is depressed, the give an antidepressant. And if the patient returns saying I’m still depressed, then they add another, or some other psychiatric medication like an atypical antipsychotic that’s advertised for depression. And so patients are walking around taking hands full of pills, and if they stop, they have withdrawal symptoms. It’s a mess. So as much as I’d like to get a lot of them medication free, at least I can slowly bring things down to something rational – to levels that meet some kind of conventional standard. And with patients with psychotic illnesses, I can lower doses, trim the polypharmacy, monitor for TD etc. There’s a lot more that can be done as a glorified social worker, and I find that very rewarding having gotten a pretty good feel for the resources in the community. And then there’s crisis intervention, and some limited psychotherapy. We have three volunteer "therapists" and so when I find a person who badly needs counseling, I can refer them.

This was foreign soil to me, but I enjoy it enough and feel like it’s helpful enough to keep at it. But I can’t help but make some observations working there. As I said, one of the observations is that a lot of the pressure to medicate comes from the patients themselves. They’d be glad for me to give out Xanax like people did in the past. It’s a major drug of abuse in these parts in spite of the hypervigilance of pharmacists, DEA, and Georgia Narcotics Bureau. I use those drugs in acute crises, in some patients with panic disorders, and in psychotic people as a way of minimizing antipsychotics – pretty standard fare. But saying "no" to requests for benzos is a major activity of every clinic day. There’s another surprising pressure from patients – antidepressants. Like everywhere, there are large numbers of people on SSRIs, and they both complain that the drugs aren’t enough and insist on continuing to take them. I’ve read all the explanations for that: television ads; withdrawal if they stop; pressure from doctors; hopes for a panacea; etc. and I’ve seen a lot of every one of those. But that’s not the whole story. They sure aren’t pressured by me. And I find that people with false hopes aren’t that hard to wean off the drugs if one is careful and have some alternative ways to improve their lives available. But I’m personally convinced that a lot of people take them for a reason that is related to drug effect. And a lot of people who stop them, come back later asking for them – even knowing the negative effects that caused them to stop in the first place. In spite of their negative effects, they get something from taking them. The question is what? not if? in my mind.

So, if I’m right, what is it? and is it good for them? I’ve never bought that the antidepressants are specific antidotes for depression, even though it’s clear that they help some people with depressed affect. They help other people too – patients with OCD, patients with anxiety disorders and panic attacks, women with bad PMS symptoms. They often work better in those conditions than in depressed people. And the notion that the antidepressant properties and the side effects can be separated is a fantasy of chemists, not a reality that I’ve seen. So I’ve assumed that the therapeutic benefit [when there is one] is part of the same complex of effects as the downside side effects. That’s why I jumped on that NZ study, because the incidence and quality of the side effects they reported feels right. And the cohort they describe is reporting a double edged sword, a compromise. That’s what I see from these drugs myself. And since I don’t think these medications are specific antidepressants, I wonder what they are actually doing.

The universe isn’t very helpful with that question. The pharmaceutical industry and a whole generation of psychiatric KOLs preach the gospel of ANTIDEPRESSANTS as if they should work specifically for all depression. If they don’t, the patient has TREATMENT RESISTANT DEPRESSION and drugs are changed, combined, augmented, the patient is genetically screened, etc. There’s even a move to have a diagnostic scheme that fits the drug’s effects [RDoC] rather than the clinical symptoms. I don’t find that line of thinking at all helpful. On the other side of the coin, there are people who point to the same things I point to on this blog – the academic-pharmaceutical alliance, the experimercials, the KOL class in psychiatry, the bio-bio-bio rhetoric, the myth of chemical imbalances, the dreams of neuroscience, the DTC television ads, etc. In their view, these drugs are all hype, created by entrepreneurs, charlatans – a mass hypnosis. All of those things happen and are real. I don’t like them either. But they don’t address the fact of the patients I see that would answer the questions exactly like the cohort in New Zealand – these medications are a double edged sword, a compromise that they prefer to the alternative.

by Joanna Moncrieff and David CohenBritish Medical Journal. 2009 338:b1963.Drugs for psychiatric problems are prescribed on the assumption that they mostly act against neurochemical substrates of disorders or symptoms. In this article we question that assumption, proposing that drugs’ action be viewed rather as producing altered, drug induced states, a view we have called the drug centred model of action. We believe that this view accords better with the available evidence. It may also allow patients to exercise more control over decisions about the value of pharmacotherapy, helping to move mental health treatment in a more collaborative direction.

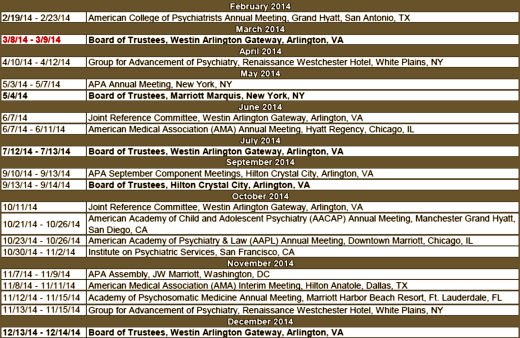

[modified to fit your screen]

I don’t mean to trivialize her work by saying this, because she has lots of important things to say, but for this post, that slide says it all clearly and simply [in spite of the mispelling – just kidding]. In my way of thinking, her drug centered model has to be correct in this instance. I know of nothing that suggests the antidepressants are specific anti-depressants [a possible exception is that sometimes, the Tricyclics reverse endogeous depression in dramatic fashion – emphasis on sometimes]. From where I sit, the SSRIs create a syndrome that is perceived as helpful by some depressed people. I say that they "turn down emotions" and use words like "blunting" or "dampening." Others say that in a more perjorative way – "numbing." That would explain their effects in GAD and OCD. I don’t know how refine that further. As I mentioned, I discovered after the fact that the place where I had prescribed them most often was in patients in therapy for PTSD who had hard emotional times along the way. I think I was trying to help "dampen" their emotions, but I wouldn’t have known to say that at the time.

This opens a very large can of worms, one that comes up frequently. The FDA deals primarily with the pharmaceutical industry, and in capitalist USA, the consideration of the industry needs is often on the front burner. Make restrictions too tight, and industry fails. In our world, industry develops the drugs. Make them too loose, and commerce carries the day – and people can get hurt or killed.

This opens a very large can of worms, one that comes up frequently. The FDA deals primarily with the pharmaceutical industry, and in capitalist USA, the consideration of the industry needs is often on the front burner. Make restrictions too tight, and industry fails. In our world, industry develops the drugs. Make them too loose, and commerce carries the day – and people can get hurt or killed. ydrocodone generally comes in 5.0 mg, 7.5 mg, and 10.0 mg pills. Zohydro™ER comes in capsules. "Each Zohydro ER capsule contains either 10, 15, 20, 30, 40, or 50 mg of hydrocodone bitartrate USP." Its assets are that it doesn’t have

ydrocodone generally comes in 5.0 mg, 7.5 mg, and 10.0 mg pills. Zohydro™ER comes in capsules. "Each Zohydro ER capsule contains either 10, 15, 20, 30, 40, or 50 mg of hydrocodone bitartrate USP." Its assets are that it doesn’t have

Back at the end of January, when I read

Back at the end of January, when I read