Posted on Thursday 4 February 2016

Annals of Internal Medicineby Eirion Slade; Henry Drysdale; Ben Goldacre, on behalf of the COMPare TeamDecember 22, 2015[online]TO THE EDITOR: Gepner and colleagues’ article reports outcomes that differ from those initially registered. One prespecified primary outcome was reported incorrectly as a secondary outcome. In addition, the article reports 5 “primary outcomes” and 9 secondary outcomes that were not prespecified without flagging them as such. One prespecified secondary outcome also was not reported anywhere in the article.

Annals of Internal Medicine endorses the CONSORT [Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials] guidelines on best practice in trial reporting. To reduce the risk for selective outcome reporting, CONSORT includes a commitment that all prespecified primary and secondary outcomes should be reported and that, where new outcomes are reported, it should be made clear that these were added at a later date, and when and why this was done should be explained.

The Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Outcome Monitoring Project [COMPare] aims to review all trials published going forward in a sample of top journals, including Annals. When outcomes have been incorrectly reported, we are writing letters to correct the record and audit the extent of this problem in the hopes of reducing its prevalence. This trial has been published and is being used to inform decision making, and this comment is a brief correction on a matter of fact obtained by comparing 2 pieces of published literature. We are maintaining a Web site [www.COMPare-Trials.org] where we will post the submission and publication dates of this comment alongside a summary of the data on each trial that we have assessed.

Annals of Internal Medicineby the EditorsDecember 22, 2015[online]… According to COMPare’s protocol, abstractors are to look first for a protocol that has been published before a trial’s start date. If they find no such publication, they are supposed to review the initial trial registry data. Thus, COMPare’s review excludes most protocols published after the start of a trial and unpublished protocols or their amendments and ignores amendments or updates to the registry after a trial’s start date. The initial trial registry data, which often include outdated, vague, or erroneous entries, serve as COMPare’s “gold standard.”

Our review indicates problems with COMPare’s methods. For 1 trial, the group apparently considered the protocol published well after data collection ended. However, they did not consider the protocol published 2 years before MacPherson and associates’ primary trial was published. That protocol was more specific in describing the timing of the primary outcome [assessment of neck pain at 12 months] than the registry [assessment of neck pain at 3, 6, and 12 months], yet COMPare deemed the authors’ presentation of the 12-month assessment as primary in the published trial to be “incorrect.” Similarly, the group’s assessment of Gepner and colleagues’ trial included an erroneous assumption about one of the prespecified primary outcomes, glycemic control, which the authors had operationalized differently from the abstractors. Furthermore, the protocol for that trial clearly listed the secondary outcomes that the group deemed as being not prespecified.

On the basis of our long experience reviewing research articles, we have learned that prespecified outcomes or analytic methods can be suboptimal or wrong. Regardless of prespecification, we sometimes require the published article to improve on the prespecified methods or not emphasize an end point that misrepresents the health effect of an intervention. Although prespecification is important in science, it is not an altar at which to worship. Prespecification can be misused to sanctify both inappropriate end points, such as biomarkers, when actual health outcomes are available and methods that are demonstrably inferior.

The Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Outcome Monitoring Project’s assessments seem to be based on the premise that trials are or can be perfectly designed at the outset, the initial trial registry fully represents the critical aspects of trial conduct, all primary and secondary end points are reported in a single trial publication, and any changes that investigators make to a trial protocol or analytic procedures after the trial start date indicate bad science. In reality, many trial protocols or reports are changed for justifiable reasons: institutional review board recommendations, advances in statistical methods, low event or accrual rates, problems with data collection, and changes requested during peer review. The Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Outcome Monitoring Project’s rigid evaluations and the labeling of any discrepancies as possible evidence of research misconduct may have the undesired effect of undermining the work of responsible investigators, peer reviewers, and journal editors to improve both the conduct and reporting of science…

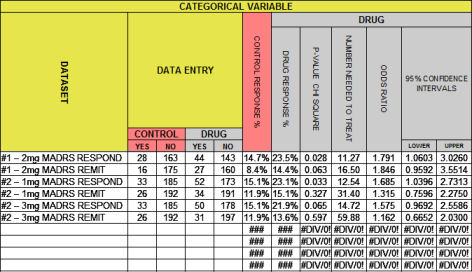

What I’m proposing is that the average medical reader can easily learn how to use a few simple tools to quickly decide if one is being served a plate of science or dish of something else. At least in my specialty, psychiatry, the industry generated clinical trial reports have been heavily weighted on the south side of something else. There are more statistical things to say before I’m done.

What I’m proposing is that the average medical reader can easily learn how to use a few simple tools to quickly decide if one is being served a plate of science or dish of something else. At least in my specialty, psychiatry, the industry generated clinical trial reports have been heavily weighted on the south side of something else. There are more statistical things to say before I’m done.