Posted on Friday 23 January 2015

With the Institute of Medicine [Sharing Clinical Trial Data: Maximizing Benefits, Minimizing Risk] and the National Institute of Health [Honoring Our Promise: Clinical Trial Data Sharing] joining the call for Data Transparency, we’re beginning to approach the details, wherein dwells the devil – what data? which trials? The whole notion of proprietary ownership of the raw dat from Clinical Trials never made any real scientific sense in the first place [see except where necessary to protect the public…, a crushing setback…, the end game… ] being justified by trade agreements. The main two arguments in this last year against Data Transparency have been protecting Commercially Confidential Information and Patient Confidentiality. But first, yet another review of the landscape:

what data?

In the discussion that follows, Summary Data refers to the CSR [Clinical Study Report] which does not necessarily or usually contain the raw data. It’s got means, standard deviations, summary tables, etc. But it doesn’t have the individual test scores or the actual clinical observations of adverse events. The IPD [Individual Participant Data] does have the raw numbers from the individual participants, but the clinical observations are in tabular form – transcribed from the CRFs [Case Report Forms] which is as close as one can get to being there. And one mustn’t forget the a priori Protocol – the plan for the study before it commenced.

which Trials?

There seems to be a consensus developing that, going forward, the more comprehensive data [IPDs and CRFs] should be available for independent review to qualified reviewers. It levels the playing field between the sponsors/investigators and the independents. But what about Clinical Trials from the past [called below legacy trials]? Here, Ed Silverman interviews one of the members of the IOM panel on that very point:

Pharmalot: WSJBy Ed SilvermanJanuary 20, 2015Last week, the Institute of Medicine issued an eagerly awaited report about sharing clinical trial data that recommends government agencies and companies provide access from research studies that they fund. The agency suggested timetables for such things as summary results and complete data packages. The move comes after heightened controversy over sharing data, how much data and the best way to do so. Among the issues that remain unsettled is the extent to which data from older trials will be shared. We spoke with Ida Sim, a professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco and a member of the IOM committee that prepared the report, about reaching back to past studies. This is an excerpt.

Pharmalot: To what extent did the committee look at sharing data from older trials?

Sim: It is addressed. We did think about it. But there are special considerations for sharing data from legacy trials… The first distinction to be made is between summary level data and individual patient level data. The average result of the trial, which is the summary, is a sort of bottom line – that’s an average result. Advocacy groups like Alltrials are asking for the release of summary level data. But the report focused on some sense of the value of individual patient-level data, and sharing the specific numbers that go into the average is much more complicated, especially for legacy trials.Pharmalot: How so?

Sim: The primary challenge is the issue of informed consent. Patients who participated in trials in the past were most likely in trials that did not include [a provision for] sharing data publicly. So if we want to now share data, ethically, investigators should go back to get informed consent from the participants. There’s another complication. Very often investigators and the staff associated with a trial have scattered. So it can be expensive and challenging to pursue a team of people, maybe years later, to have them pursue this.Pharmalot: Should that preclude all older trials?

Sim: Well, that said, for major significant trials that do influence decisions for clinical care, we recommend that, on a case-by-case basis, legacy studies should be prioritized for data sharing. But we have to be pragmatic and realistic. These are issues that have been going on for a long time. I think the committee has been building on prior work [of others] and recognizing there were instances of cherry picking of results, which started the whole movement of registration disclosure [registering trials with ClinicalTrials.gov]. Now, we’re pushing for the next level. But it’s incremental.Pharmalot: Do you worry that companies may be let off the hook?

Sim: They have been really. The real question is what to extent can we go back and put them on the hook. It’s a question of balance. There are studies from academic investigators, who also have not been upfront [about disclosure]. There are problems of transparency across the whole clinical trial enterprise and the concerns apply to all clinical trials. The ones from the pharmaceutical industry are just more apparent to the public…

But, as Dr. Sim says, those legacy trials are going to contain a lot of jury-rigged science. And as a scientist/physician, I feel betrayed, and I want it exposed in all its gory detail. I, and the rest of medicine, have been actively misinformed – on purpose. Our patients have been actively misinformed – on purpose. And I personally believe that the companies and their medical allies will just do it again if there’s not a truth and reconciliation period to mark what happened in stone. But that’s my opinion, my bias that surely affects my logic supporting full Data Transparency for legacy trials. From my vantage, the operative saying here is, "Don’t do the crime, if you can’t do the time."

But there’s another good very reason for full Data Transparency for legacy trials, particularly in psychiatry. The drugs in question are now off-patent – widely available in generic form, inexpensive, and still in heavy use. Managed Care reviewers still hawk them as cost-cutters. And they’re not going to be replaced any time soon. Nor is it likely that Bill Gates, PHARMA, or the NIMH will finance any new trials to restudy them properly. But we can look at the raw data from the original trials. And fortunately, the sleight of hand occurred primarily in the analytic and publication processes that came after the blinds were broken. So those legacy trials are the very ones that need to be reanalyzed and meta-analyzed by independent investigators playing with a full deck. Without an accurate and very public re-appraisal, the problem is going to be perpetuated for decades.

It looks as if the idea of Data Transparency has finally become mainstream.

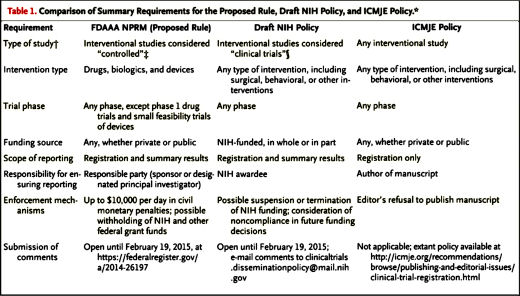

It looks as if the idea of Data Transparency has finally become mainstream.  So below, we’re offered two chances to comment on the coming changes in Data Transparency policy – with the Europeans Medicines Agency and the NIH. The last time the EMA asked, many of us responded and they actually changed what they were doing. And I got a note from the main poopah. And this time, I got a personal request to comment [well sort of personal as in "Dear all"]. But my point holds. If there were ever a right time to respond, this is our moment. Same with the NIH. We‘re on their radar now and it’s time to start being a blip. Please click the red underlined links…

So below, we’re offered two chances to comment on the coming changes in Data Transparency policy – with the Europeans Medicines Agency and the NIH. The last time the EMA asked, many of us responded and they actually changed what they were doing. And I got a note from the main poopah. And this time, I got a personal request to comment [well sort of personal as in "Dear all"]. But my point holds. If there were ever a right time to respond, this is our moment. Same with the NIH. We‘re on their radar now and it’s time to start being a blip. Please click the red underlined links…

It was APA, along with NIMH and academic psychiatry leadership in the latter part of the last century, that helped the field to develop to its current prominence. It is incumbent upon us to focus our attention on these issues so that our academic departments remain strong enough to allow care, new treatments, and education to move forward effectively at a time when our services have never been more essential or the potential for fundamental breakthroughs greater.

It was APA, along with NIMH and academic psychiatry leadership in the latter part of the last century, that helped the field to develop to its current prominence. It is incumbent upon us to focus our attention on these issues so that our academic departments remain strong enough to allow care, new treatments, and education to move forward effectively at a time when our services have never been more essential or the potential for fundamental breakthroughs greater. Long psychotherapies were being billed to medical insurance, a practice that had to change. And there were competitive wars with other mental health specialties. All were problems in need of urgent attention. While there was nothing so wrong with the manifest solution [the APA’s DSM-III], the method of change [

Long psychotherapies were being billed to medical insurance, a practice that had to change. And there were competitive wars with other mental health specialties. All were problems in need of urgent attention. While there was nothing so wrong with the manifest solution [the APA’s DSM-III], the method of change [ But now it’s the dry season again. PHARMA finally exited the picture three years ago, and the impact of its absence on the economy of academic psychiatry is obviously widely felt. The APA’s recent failed DSM-5 enterprise also did little for the current state of the specialty. There has been more than a quarter-century-long alliance among academic psychiatry departments, the APA, the NIMH, and the pharmaceutical industry. The practice of psychiatry has come to be centered on outpatient medication management, and many patients have been "left behind." Add in countless examples of scientific misbehavior and misrepresented authorship in the Clinical Trial literature, particularly with these psychoactive drugs. So while the controversies and some of the players may be similar, this is not the same psychiatry that faced that dry season in the 1970s.

But now it’s the dry season again. PHARMA finally exited the picture three years ago, and the impact of its absence on the economy of academic psychiatry is obviously widely felt. The APA’s recent failed DSM-5 enterprise also did little for the current state of the specialty. There has been more than a quarter-century-long alliance among academic psychiatry departments, the APA, the NIMH, and the pharmaceutical industry. The practice of psychiatry has come to be centered on outpatient medication management, and many patients have been "left behind." Add in countless examples of scientific misbehavior and misrepresented authorship in the Clinical Trial literature, particularly with these psychoactive drugs. So while the controversies and some of the players may be similar, this is not the same psychiatry that faced that dry season in the 1970s.

The time leading up to the 2004 Black Box Warning was the heyday of psychopharmacology when drugs continued to flow from the mythical PHARMA pipeline. Direct-to-Consumer ads for antidepressants blanketed the media. Drug reps detailing psychoactive drugs and KOLs speaker’s bureaus were focusing on primary care physicians, specifically because of the much broader market than that reached by psychiatrists. Rather than see the de-escalation of antidepressant prescriptions as ignoring depressed teens, it seems much more plausible to suppose that the Black Box Warning appropriately neutralized the hype that had bombarded the general practitioners in those days – leading to more rational prescribing.

The time leading up to the 2004 Black Box Warning was the heyday of psychopharmacology when drugs continued to flow from the mythical PHARMA pipeline. Direct-to-Consumer ads for antidepressants blanketed the media. Drug reps detailing psychoactive drugs and KOLs speaker’s bureaus were focusing on primary care physicians, specifically because of the much broader market than that reached by psychiatrists. Rather than see the de-escalation of antidepressant prescriptions as ignoring depressed teens, it seems much more plausible to suppose that the Black Box Warning appropriately neutralized the hype that had bombarded the general practitioners in those days – leading to more rational prescribing.