As a child, I frequently visited my grandparents in a small Georgia town. They lived in an old Victorian house that was filled with wonderful cousins and "show people" – friends from their earlier days as wandering Vaudevillians who passed through town. It was a magical place etched forever in my mind. One of my favorite things was visiting the old couple in the cottage next door. The husband had Diabetes in a time when that was difficult to manage, so he was rarely seen. But the wife, an elderly lady with multiple deformities from Rheumatoid Arthritis was always on the porch, glad to see me, giving out various treats and telling magical stories of her own. She called me her "pal." She had been a traveling Vaudevillian herself until she was stricken with a storm of arthritis that left her barely able to get to her front porch, much less sing and dance. So her stories were of her pre-RA adventures going from town to town and doing shows on the Mississippi River boats – the vacation cruise liners of the day. She loved telling those stories and I loved hearing them. In medical training, it never occurred to me that my choice of specialties, Immunology and Rheumatology, had anything to do with my childhood "pal," but there’s little question in my mind now that she was perhaps the deciding factor [in that place that runs in the background of things].

Rheumatoid Arthritis comes in many flavors, but a "storm" is one of them. By the time it passes, the joints are badly damaged leaving the deformities in their wake for the duration, even though the active inflammatory process has passed. By the time I came along, we were loaded with treatments beyond the traditional supportive care. We had anti-inflammatories, antimalarials, gold injections, and, of course, corticosteroids. The immunosuppressives were experimental, but definitely on the way. None of the drugs treated RA, whatever it is. They treated the consequences, but doctors and patients were glad to have them nonetheless. And, by the way, they’re all poisons with predictable side effect profiles and potential dire consequences with extended [and sometimes short-term] use. I never saw an acute case that turned out like my "pal." We could abort that outcome. But I saw those older patients in the clinic who were still plagued by the indelible deformities from the days before we had the poisons. And I saw another group of older patients in that same clinic, still plagued by the consequences of the too liberal or extended use of corticosteroids during their earlier days as "wonder" drugs.

In case you’re wondering where I’m headed with these reflections, it’s my response to a lively and interesting discussion in the comments to my post fire in the belly…. But I’m not quite ready just yet to connect the dots…

Also in Rheumatology, we had biomarkers – tests that were part of making the diagnosis. We had RA tests, LE preps [Systemic Lupus Erythematosis], ANA tests [anti-nuclear antibodies], and a bunch of others with less specificity. But those biomarkers had nothing to do with some ultimate cause, or if they did, we didn’t know it. They were like the treatments, tests of the consequences, the inflammatory responses – though we chased them to the ends of the earth looking for a cause. When last I checked, these were diseases of unknown origin and the biomarkers were for chronic inflammation of various kinds – not the diseases.

When I got to psychiatry as a late-comer, the analogies with psychotic illness weren’t lost on me – diseases of unknown origins that could profoundly alter the course of a life, treatable with poisons with predictable side effect profiles and potential dire consequences with extended [and sometimes short-term] use. There was another analogy in that psychotic illnesses either clear [Affective Disorders] or improve [Schizophrenia] with time. I was used to treating one bad disease [RA, Schizophrenia] by causing another [Cushing’s Disease, Neurolepticization], and I had no illusion that there was anything slightly easy about walking that tightrope [living with that double-bind]. I was uneasy about the way my fellow residents used medications so liberally. They thought my reserve was "quaint" – maybe "old fashioned."

I had been writing about the Dr, George Brooks’ Vermont study in the 1950s when Thorazine was first introduced. Around 40% of his "back ward" patients responded. He developed an intensive intervention, something of a therapeutic community and was able to move most of those that remained into the community. Courtenay Harding published a [very] long term follow-up [mean = 32 years] in which they rediagnosed the cases using modern [DSM-III] criteria, and compared them to a contemporary cohort in Maine who had not been through a rehab program. By any dimension, the Vermont study demonstrated an impressive outcome – certainly nothing like the grim predictions of the past, and showed the importance of going beyond simply using antipsychotic medication. By my read, the medication was an essential ingredient, "but only an ingredient, not the ingredient." I personally really enjoyed reading the study [in part because it mirrored my own thoughts].

In the comments, the discussion turned to the writing of Joanna Moncrieff [eg How do psychiatric drugs work?][see also not with a Hamilton Rating Scale…]. She contrasts a disease centered model [the medication treats the disease itself] and a drug centered model [the medication creates an altered state, and the therapeutic effects are secondary to the altered state]. In the comments, there was an argument about the utility of her point. I avoid taking sides when people I respect argue with each other and try to just listen to learn, seeing argument and debate as our greatest legacy from the scholars of old. But I thought I’d add in my own thoughts about Dr. Moncrieff’s point.

When I first read Dr. Moncrieff’s writings, I didn’t get it. I already thought what she said. I had never had a single moment in my life thinking antipsychotics were disease-specific. For that matter, I only thought antidepressants were disease-specific for a short time after a particularly eloquent lecture in my Internist years of yore [I got over it quickly]. And one would have to be blind not to notice that both groups of drugs could and did create altered states. I had a similar reaction on reading Robert Whitaker’s books when he talked about the dangers of medications and particularly their their continual use. I agreed with him, but I always had. I knew that many recommended keeping people on antipsychotics all the time to prevent relapses, but I also knew that patients often didn’t like taking them and stopped. I had seen enough obtunded states and Tardive Dyskinesia to know that I wanted no part of causing either. And I’m also old enough to have seen the patients like those rescued by Dr. Brooks, crippled by years of unmodifed psychotic illness – crippled in a different way from my childhood "pal," but crippled nevertheless.

And I’ve heard activists talk about psychiatrists drugging patients for my whole career – like it’s something we want to do or don’t understand the consequences of or enjoy. And I listened to Dr. Szasz’s point about the myth of mental illness – even read some of his books. And I’ve heard the recommendations and read the guidelines for "staying on meds" ad infinitum. And when I was a chief resident and later a training director, the residents and medical students quickly learned not to present a case to me with "stopped taking her meds" as an explanation for a relapse, knowing they were in for one of my diatribes that started with, "I wonder why she stopped taking her meds? Let’s go ask her," as I marched them en masse to the ward to see the patient.

I understand why people who work in some places, particularly mental health centers or academic jobs, gravitate towards the "stay on meds" end of the spectrum. Patients going off meds do frequently relapse. It’s not very good for them [and it’s exhausting]. And I understand why people who see the long term consequences of these medications come to oppose their existence. I decided that I had to make my own peace with all of those things and I had trouble getting there when I thought about "all patients." I am by training and preference an n=1 doctor and what usually happens when I try to think about "all" anythings is that I end up with a headache. I also see physicians as advisers and so the involuntary stuff isn’t my cup of tea. I’m actually pretty good at it, but I just don’t like it [which is probably why I was good at it]. So public mental health wasn’t going to be my choice, even though by temperment and history, I’m afflicted with a "do gooder" gene.

What I decided was that my job was to learn everything I could learn about these medicines and the illnesses they were used to treat, and then deal with one patient at a time – the ones that saw me as their doctor and I saw as my patients. That’s the way I learned to be a doctor and it was, in my opinion, the right way to do things. I followed a reasonable number of patients with psychotic illnesses over the years. I always aimed for them to be medication free, but only occasionally achieved that goal. We had to settle for either intermittently medication free, or medications minimal. I learned that if I was more liberal with antianxiety drugs than usual, I could minimize the antipsychotics more easily because the patients tended to use them for their anxiety. To be honest, the Rheumatologists who had taught me to carefully manage their even more toxic medications were more helpful than the psychiatrists or their guidelines in my own work.

I personally believe that these patients are really helped by long contact with professionals and others who know their illnesses, vulnerabilities, and pitfalls. I believe judicious use of neuroleptics is an important, and sometimes essential, part of the picture. And I agree that the best way to work is collaboratively as an adviser rather than as an authority figure. As for Dr. Moncrieff, I came to see why she says what she says by listening to the KOLs and reading their guidelines. They need to hear it. But I see that point everywhere in interventional Medicine. As an old man, I guess I see most "meds" as poisons or potential poisons. The skill is maximizing the useful effects, minimizing the noxious effects, and living with the constant terror of doing long term harm always sitting on your shoulder. I now think that’s what Joanna Moncrieff is saying and if I’m right, I agree with her. I wish she’d aim it a bit more towards the people who most need to hear it, and not at those of us who have always known it.

I still wish my childhood "pal" had been born in my time – a time of the latter-day poisons that might’ve allowed her more of the life she wanted to live…

These days, the Clinical Trial itself is often spread among multiple sites, coordinated by a contracted CRO [Clinical Research Organization]. The subjects are randomized and double blinded so neither the study staff nor the subjects know what medication any subject is taking. Each of the tests and observations throughout the duration of the trial are recorded on a variety of individual Case Report Forms [CRFs] – the true Raw Data from a Clinical Trial. When the last subject enrolled completes the study, the stacks of CRFs are abstracted – turned into analysis ready tables called the Individual Participant Data [IPD], usually in an electronic format. This whole process takes place while the study is still fully blinded. The IPDs that tabulate the numeric or categorical scores from tests likely mirror the CRF data [but those cataloging Adverse Effects and other notations can lose something in translation].

These days, the Clinical Trial itself is often spread among multiple sites, coordinated by a contracted CRO [Clinical Research Organization]. The subjects are randomized and double blinded so neither the study staff nor the subjects know what medication any subject is taking. Each of the tests and observations throughout the duration of the trial are recorded on a variety of individual Case Report Forms [CRFs] – the true Raw Data from a Clinical Trial. When the last subject enrolled completes the study, the stacks of CRFs are abstracted – turned into analysis ready tables called the Individual Participant Data [IPD], usually in an electronic format. This whole process takes place while the study is still fully blinded. The IPDs that tabulate the numeric or categorical scores from tests likely mirror the CRF data [but those cataloging Adverse Effects and other notations can lose something in translation]. When the blind is broken, the IPD datasets are ready for Analysis. That’s when the investigators, sponsors, and statisticians get their first look at the data sorted by treatment, and can apply all the tricks of their trade that tell us all if the study drug separates from placebo, the magnitude of the effect, and whether there are significant adverse effects from use. At this point, the whole process is turned into something called a Clinical Study Report [CSR], a long narrative document that tells the story from start to finish including the results. One thing to note, usually the relevant IPD tables are appended to the CSR, but that’s not always true. So it’s important when CSRs are being offered to find out if they have the unanalyzed data attached or not.

When the blind is broken, the IPD datasets are ready for Analysis. That’s when the investigators, sponsors, and statisticians get their first look at the data sorted by treatment, and can apply all the tricks of their trade that tell us all if the study drug separates from placebo, the magnitude of the effect, and whether there are significant adverse effects from use. At this point, the whole process is turned into something called a Clinical Study Report [CSR], a long narrative document that tells the story from start to finish including the results. One thing to note, usually the relevant IPD tables are appended to the CSR, but that’s not always true. So it’s important when CSRs are being offered to find out if they have the unanalyzed data attached or not.

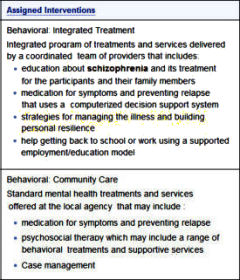

So when I look at the RAISE program and the push to implement it on a large scale, I think several things. I see nothing in the

So when I look at the RAISE program and the push to implement it on a large scale, I think several things. I see nothing in the