Posted on Saturday 23 August 2014

It’s unlikely that anyone reading this blog or following the peculiar trajectory of academic and organized psychiatry doesn’t know a lot about Charlie Nemeroff and his fall from "Boss 0f Bosses" as Chairman at Emory. He’s become a paradigm for so many things – ghost writing, conflicts of interest, speaker’s bureaus, advisory boards, wheelings-and-dealings, etc. After the fall in 2008, he landed on his feet as Chairman in Miami by 2009 and by 2012 he got himself back on the Grand Rounds Circuit with the topic, The Neurobiology of Child Abuse: Treatment Implications and as an NIMH grantee with PROSPECTIVE DETERMINATION OF PSYCHOBIOLOGICAL RISK FACTORS FOR PTSD [speechless…].

During Dr. Nemeroff’s time as Chairman at Emory, I had already left the Department there as a full time faculty person during the revolution in psychiatry in the 1980s, remaining on the clinical faculty. One interest was PTSD, the psychological part, but I didn’t even know that the chairman of my department was following this other path, one he still follows. I don’t personally believe PTSD has anything to do do with neurobiology or psychobiology, but what I think is not what this post is about. It’s about something known as grantsmanship and wasted research dollars.

I’m not the only person that follows the Travels with Charlie. Carl Elliot of Fear and Loathing in Bioethics points us to Dr. Nemeroff’s coming visit to the Department of Psychiatry at his University of Minnesota.

| Grand Rounds – 2014-2015 | |

|

|

|

| September 3, 2014 | Grand Rounds: TBD Presenter: Charles B. Nemeroff, MD, Professor and Chair, Dept. of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and Director, Center on Aging, University of Miami |

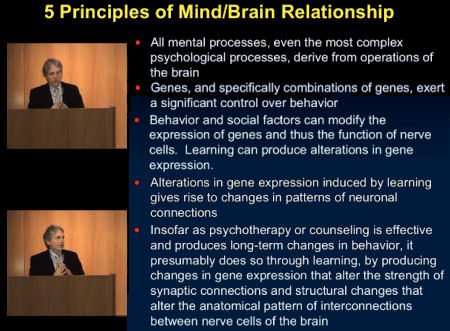

I don’t know if the topic will be The Neurobiology of Child Abuse: Treatment Implications like it was at NYU or in London. The video of the NYU version has unfortunately been taken down, but here’s a synopsis of his closing slides:

I don’t happen to believe any of the speculative parts of that [3, 4, & 5]are known or even likely, but like I said, what I think is not what this post is about. Here’s a piece of that grant write-up for orientation:

| Although the majority of trauma victims experience the cardinal symptoms of re-experiencing, avoidance and hyperarousal, for the large majority of such individuals, these symptoms do not become chronic nor do they develop syndromal PTSD. It is important to identify the large minority of trauma victims with a high likelihood of developing PTSD because of the very significant medical and psychiatric morbidity and mortality associated with this disorder. There is already considerable evidence that the likelihood of developing PTSD after trauma exposure is due to a combination of genetic and environmental factors. This two-site, linked R-01 application seeks to utilize state-of-the art advances in genomics, transcriptomics and epigenetics, coupled with comprehensive clinical and psychological measures, to address this seminal unanswered question in PTSD clinical service and research… |

I don’t happen to believe there is"already considerable evidence that the likelihood of developing PTSD after trauma exposure is due to a combination of genetic and environmental factors" either, but…

So to the grant itself. So far, we’re into it for a bit over a million NIMH dollars. This is the second time around for this project. Last time, they recruited subjects from hospital waiting rooms and ads on rapid transit [MARTA]. How did they get funded to do it again? I’m not sure, but I think it’s that they’re taking different measurements and using different analyses [?], but what I really think is that Dr. Nemeroff is a master of grantsmanship…

| To achieve this goal, 500 trauma-exposed subjects will be recruited at the University of Miami Ryder Trauma Center and the Emory University affiliated Grady Memorial Hospital and followed at regular intervals for one year. This focused, hypothesis-driven study will scrutinize previously identified psychological and biological risk factors. Genetic risk factors include polymorphisms of the ADCYAP1R1, FKBP5, DAT, BDNF, COMT, CRFR1, 5HTTLPR, RGS2, GABA2 and 5HT3R genes, novel genetic and epigenetic risk factors and most importantly, the primary downstream effects of these genomic and epigenetic findings by the use of conventional and newer statistical modeling methods. |

We were all mystified that he got an NIMH grant at all with his track record [speechless…], and particularly with this topic – a tired remnant from the days when the biology-is-everything mantra was king. I doubt that anyone much thinks that anything will come from this study. So why would he be so quickly rehired after being definitively discredited and how did he get a grant for this of all topics? That is what this post is about. Back in the day, Dr. Nemeroff became the paradigmatic insider. He knew all the people in power [some of whom he’d helped to get there]. And he was an expert in parlaying his influence in raising money from the pharmaceutical companies and the NIMH. He got away with some outrageous antics because he brought home the money to his university and department, so people looked the other way. Even in disgrace, he was still an effective power broke – thus landing on his feet. And what’s the point? He’s still bringing home the bread. And, oh look, three fifths of the way through this grant life, what has been charged to it?

It’s pretty easy to see that these articles don’t have anything to do with the PROSPECTIVE DETERMINATION OF PSYCHOBIOLOGICAL RISK FACTORS FOR PTSD. But that’s not to say that the study isn’t going on. I expect at the end we’ll be treated to slides of findings added to those from the other time around. But it’s highly unlikely that the results will add anything to our understanding of biology or PTSD. At best, they will become references for a further grant application. Over the course of the years, Dr. Nemeroff has been PI on ~$45M worth of NIMH Grants. To my knowledge, none have produced anything that is a lasting addition to the scientific record [note the Senator Grassley Gap 2008-2011]:

When I hear the criticisms of the modern bio-bio-bio psychiatry, while I often agree, I add something else in my mind – motives. The upper layer of academic psychiatry is populated predominantly by people selected by their medical schools because they can do some version of what’s described in this post – bring home the bacon from the NIMH, industry, foundations, et cetera. And for thirty plus years, they’ve talked about little other than biological research and pharmaceutical studies, selecting their future academic colleagues from the like-minded pool [that got us where we are today]. Dr. Nemeroff isn’t an exception, he’s just bolder, more reckless – reckless enough to have been busted for a time. And that’s just the NIMH story. The financing from pharmaceutical companies was probably even more impressive, and flexed the same muscles as the NIMH grantsmanship. He’s just one among many. I recently described a $50M version from UT Southwestern [retire the side…] – equally expensive, with equally non-memorable results. And there are too many more examples.

by Boadie W Dunlop,corresponding author1 Barbara O Rothbaum,1 Elisabeth B Binder,1,2 Erica Duncan, Philip D Harvey, Tanja Jovanovic,1 Mary E Kelley,5 Becky Kinkead, Michael Kutner,5 Dan V Iosifescu, Sanjay J Mathew,7 Thomas C Neylan,8 Clinton D Kilts, Charles B Nemeroff, and Helen S MaybergTrials. 2014; 15: 240.

Acknowledgements

Funding for the study is provided from a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health, U19 MH069056 (BWD, HM). Additional support was received from K23 MH086690 (BWD) and VA CSRD Project ID 09S-NIMH-002 (TCN). GlaxoSmithKline contributed the study medication and matching placebo, as well as funds to support subject recruitment and laboratory testing. GSK is uninvolved in the data collection, data analysis (excepting some pharmacokinetic analysis), or interpretation of findings. The GSK561679 compound is currently licensed by Neurocrine Biosciences, which will also perform pharmacokinetic analyses.

by Nemeroff CB, Widerlöv E, Bissette G, Walléus H, Karlsson I, Eklund K, Kilts CD, Loosen PT, Vale W.Science. 1984 Dec 14;226(4680):1342-4.

The possibility that hypersecretion of corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) contributes to the hyperactivity of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis observed in patients with major depression was investigated by measuring the concentration of this peptide in cerebrospinal fluid of normal healthy volunteers and in drug-free patients with DSM-III diagnoses of major depression, schizophrenia, or dementia. When compared to the controls and the other diagnostic groups, the patients with major depression showed significantly increased cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of CRF-like immunoreactivity; in 11 of the 23 depressed patients this immunoreactivity was greater than the highest value in the normal controls. These findings are concordant with the hypothesis that CRF hypersecretion is, at least in part, responsible for the hyperactivity of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis characteristic of major depression.hat-tip to James O’Brien…

This is not really a blog post – more like a library of selected readings. Over the last year, there has been a dialog about the use of maintenance antipsychotic medication in the long term treatment of schizophrenic patients scattered around in various publications that hinges on an article published in JAMA Psychiatry last summer. It’s a Dutch Study that followed patients with First Episode Schizophrenic illness for 7 years. First the abstract of the article and an excerpt from the accompanying editorial [both behind a paywall]:

This is not really a blog post – more like a library of selected readings. Over the last year, there has been a dialog about the use of maintenance antipsychotic medication in the long term treatment of schizophrenic patients scattered around in various publications that hinges on an article published in JAMA Psychiatry last summer. It’s a Dutch Study that followed patients with First Episode Schizophrenic illness for 7 years. First the abstract of the article and an excerpt from the accompanying editorial [both behind a paywall]: When I read this, I had a déjà vu moment. I was reminded of the early days of Prozac® [also from Eli Lilly]. Package inserts aren’t my primary resource when a new drug shows up, but I’ve always read the PDR [Physician’s Desk Reference] which is essentially a book of package labels for all of our drugs. Over my fifty years in medicine, the PDR has gotten much thicker and the print has gotten much smaller, so I have one of those plastic wallet card magnifiers as an always-around book-mark stuck in my copy. Whenever I learn of a new drug I might prescribe, I always check the PDR [package label] for adverse events and drug interactions. I can’t find the original Prozac® label, but I remember reading about the sexual side effects back in the day. And what it said and what turned out to be true weren’t even in the same state, much less the same county. I sure was no "learned intermediary" in that instance. It’s the first time I can recall feeling like I was being gamed about a drug. I feel the same thing reading this final

When I read this, I had a déjà vu moment. I was reminded of the early days of Prozac® [also from Eli Lilly]. Package inserts aren’t my primary resource when a new drug shows up, but I’ve always read the PDR [Physician’s Desk Reference] which is essentially a book of package labels for all of our drugs. Over my fifty years in medicine, the PDR has gotten much thicker and the print has gotten much smaller, so I have one of those plastic wallet card magnifiers as an always-around book-mark stuck in my copy. Whenever I learn of a new drug I might prescribe, I always check the PDR [package label] for adverse events and drug interactions. I can’t find the original Prozac® label, but I remember reading about the sexual side effects back in the day. And what it said and what turned out to be true weren’t even in the same state, much less the same county. I sure was no "learned intermediary" in that instance. It’s the first time I can recall feeling like I was being gamed about a drug. I feel the same thing reading this final  There were only 5 months between the FDA Approval of Cymbalta® and the submission of this Lilly-funded article. So they had to know about the frequency of discontinuation symptoms back then. After all, it was their own trials being reviewed. And this study is not mentioned in any of the label revisions along the ten years of patent protection. Surely they weren’t counting on all doctors to be subscribers to the Journal of Affective Disorders. And I hardly think that the blurb in that package insert comes close to alerting us "learned intermediaries" to the true incidence of discontinuation symptoms. Cymbalta® appeared after I retired and it’s not available in the charity clinic where I work, so I’ve never prescribed it or even looked it up in the PDR. It has only just gone off-patent. But it’s easy to see why the motion to dismiss the class action suit was denied. I had no idea that the withdrawal symptoms were so frequent until I started writing this post.

There were only 5 months between the FDA Approval of Cymbalta® and the submission of this Lilly-funded article. So they had to know about the frequency of discontinuation symptoms back then. After all, it was their own trials being reviewed. And this study is not mentioned in any of the label revisions along the ten years of patent protection. Surely they weren’t counting on all doctors to be subscribers to the Journal of Affective Disorders. And I hardly think that the blurb in that package insert comes close to alerting us "learned intermediaries" to the true incidence of discontinuation symptoms. Cymbalta® appeared after I retired and it’s not available in the charity clinic where I work, so I’ve never prescribed it or even looked it up in the PDR. It has only just gone off-patent. But it’s easy to see why the motion to dismiss the class action suit was denied. I had no idea that the withdrawal symptoms were so frequent until I started writing this post.

In the case of Eli Lilly’s Prozac®, the incidence of sexual side effects was minimized. With Lilly’s Zyprexa®, the tendency for significant weight gain and Diabetes was downplayed. Comes now Lilly’s Cymbalta®, and we find yet another inconvenient [secret] truth, a regular Withdrawal Syndrome now increasingly moving into the light of day as the drug goes off-patent. What has this learned intermediary gleaned from Eli Lilly? They specialize in deceit when it comes to reporting the adverse effects of their psychiatric drugs. That’s what…

In the case of Eli Lilly’s Prozac®, the incidence of sexual side effects was minimized. With Lilly’s Zyprexa®, the tendency for significant weight gain and Diabetes was downplayed. Comes now Lilly’s Cymbalta®, and we find yet another inconvenient [secret] truth, a regular Withdrawal Syndrome now increasingly moving into the light of day as the drug goes off-patent. What has this learned intermediary gleaned from Eli Lilly? They specialize in deceit when it comes to reporting the adverse effects of their psychiatric drugs. That’s what…

There are two always-available criticisms of physicians’ decisions: "That’s just what you think! What’s your evidence base?" and "You’re just following a guideline by rote and not seeing the person in front of you!" At one time or another, each of those negative epithets might well be accurate – sometimes both apply. But somewhere in recent times, the battle cry of evidence based medicine has shifted the balance and fostered the notion that the guidelines derived from groups dictate the best course for an individual case

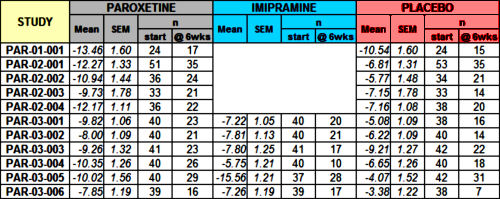

There are two always-available criticisms of physicians’ decisions: "That’s just what you think! What’s your evidence base?" and "You’re just following a guideline by rote and not seeing the person in front of you!" At one time or another, each of those negative epithets might well be accurate – sometimes both apply. But somewhere in recent times, the battle cry of evidence based medicine has shifted the balance and fostered the notion that the guidelines derived from groups dictate the best course for an individual case  – implying a uniformity among people and a strict objectivity to medical care that is illusory. Randomized Clinical Trials, Rating Scales, Statistical Significance, FDA Approval, Expert Opinions, and all the other ways we try to extract objective markers from subjective phenomena are vital tools in the medical toolbox, but only that – tools…

– implying a uniformity among people and a strict objectivity to medical care that is illusory. Randomized Clinical Trials, Rating Scales, Statistical Significance, FDA Approval, Expert Opinions, and all the other ways we try to extract objective markers from subjective phenomena are vital tools in the medical toolbox, but only that – tools…