This is the lead-in to the Introduction

[but it’s not the story]

Back in February 2012 [a book review…], I read an article by statistician Robert Gibbons et al that purported to be a meta-analysis showing that antidepressants are effective in adolescent depression and are not associated with suicidality as a side effect. It turned into a cause célèbre when I found that he made a habit of opposing any Black Box Warning. He’d done it with Neurontin® before. Since then, he’s done it with Chantix®. His pattern has been repetitive. He reports on data from the drug company given to him exclusively – not publicly available – attacking the FDA’s Black Box Warning. Then there’s a simultaneous media campaign that follows [very monotonous…]. The papers don’t show the data and are filled with so much statistic-ese that I can’t really vet them. My presumptive conclusion has been that he’s a PHARMA shill, specifically working for Pfizer/Wyeth [since their drugs are involved]. When confronted about his articles, he generally spits back.

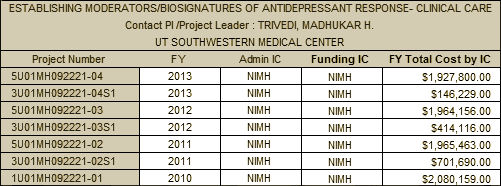

In another thread, Dr. Gibbons has been developing some computerized psychometric screening tools for anxiety and depression, funded by the NIMH:

by Robert D. Gibbons, David J. Weiss, Paul A. Pilkonis, Ellen Frank, Tara Moore, Jong Bae Kim, and David J. Kupfer.

American Journal of Psychiatry. published on-line Aug 9, 2013

Conclusions: Traditional measurement fixes the number of items but allows measurement uncertainty to vary. Computerized adaptive testing fixes measurement uncertainty and allows the number and content of items to vary, leading to a dramatic decrease in the number of items required for a fixed level of measurement uncertainty. Potential applications for inexpensive, efficient, and accurate screening of anxiety in primary care settings, clinical trials, psychiatric epidemiology, molecular genetics, children, and other cultures are discussed.

The Computerized Adaptive Diagnostic Test for Major Depressive Disorder [CAD-MDD]:

A Screening Tool for Depression

by Robert D. Gibbons, Giles Hooker, Matthew D. Finkelman, David J. Weiss, Paul A. Pilkonis, Ellen Frank, Tara Moore, and David J. Kupfer.

Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2013 74[7]:669–674.

Conclusions: High sensitivity and reasonable specificity for a clinician-based DSM-IV diagnosis of depression can be obtained using an average of 4 adaptively administered self-report items in less than 1 minute. Relative to the currently used PHQ-9, the CAD-MDD dramatically increased sensitivity while maintaining similar specificity. As such, the CAD-MDD will identify more true positives [lower false-negative rate] than the PHQ-9 using half the number of items. Inexpensive [relative to clinical assessment], efficient, and accurate screening of depression in the settings of primary care, psychiatric epidemiology, molecular genetics, and global health are all direct applications of the current system.

by Gibbons RD, Weiss DJ, Pilkonis PA, Frank E, Moore T, Kim JB, and Kupfer DJ.

Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012 69[11]:1104-12.

CONCLUSIONS Traditional measurement fixes the number of items administered and allows measurement uncertainty to vary. In contrast, a CAT fixes measurement uncertainty and allows the number of items to vary. The result is a significant reduction in the number of items needed to measure depression and increased precision of measurement.

These tests iterate towards results quickly by drawing questions from a bank of questions based on the last response rather than presenting a fixedset of questions, shortening the test time. That invalidates their use in clinical trials. They are obviously screening tests for anxiety and depression designed for a mass market. And in the 2012 paper, they mentioned that they were considering commercial development. In July, Dr. Bernard Carroll wrote a letter to the editor criticizing the test along several axes, concluding that it was Not Ready For Prime Time:

by Bernard J. Carroll, MBBS, PhD, FRCPsych

JAMA Psychiatry. 2013 70[7]:763.

This is the actual Introduction

[still not the story, but getting closer]

Posted right below Dr. Carroll’s letter was their response signed by the authors. It ends with:

In summary, it is very clear that Carroll is not a fan of multidimensional item response theory and computerized adaptive testing as applied to the process of psychiatric measurement. It is, however, completely unclear that his lack of enthusiasm is based on any scientifically rigorous foundation. Indeed, his knowledge of these methods seems lacking. Finally, Carroll is quick to point out the acknowledged potential conflicts of others as if they have led to bias in reporting of scientific information. In this case, it is Carroll who has the overwhelming conflict of interest. As developer,owner,and marketer of the Carroll Depression Scale–Revised, a traditional fixed-length test, it is not surprising that the paradigm shift described in our article would be of serious concern to him.

The general tone of his reply was contemptuous, but ending it with a full court double ad hominem was vicious, even for him [I’m assuming Gibbons wrote it based on his previous outings]. But playing amateur night as a psychoanalyst and accusing Carroll of being motivated by something like greed or envy because of his own Depression Scale was a new low for Gibbons [and a big mistake], particularly since Dr. Carroll had declared that interest in his original letter. All was quiet on the western front for a time. Then on November 20, this was published in JAMA Psychiatry:

by Robert D. Gibbons, PhD, David J.Weiss, PhD, Paul A. Pilkonis, PhD, Ellen Frank, PhD, and David J. Kupfer,MD.

JAMA Psychiatry. Published Online: November 20, 2013. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.3888

To the Editor: We apologize to the editors and readers of JAMA Psychiatry for our failure to fully disclose our financial interests in an article1 that reported a diagnostic tool, the Computerized Adaptive Test for Depression [CAT-DI]. Following acceptance of the paper, we disclosed that “The CAT-DI will ultimately be made available for routine administration, and its development as a commercial product is under consideration.” The company that owns the rights to CAT-DI and several related tests is Psychiatric Assessments, Inc [PAI], which uses the trade name of Adaptive Testing Technologies [ATT] on a website describing these tests. Lead author Robert D. Gibbons, PhD, is the president and founder of PAI,which was incorporated in Delaware in late 2011, then registered to do business in Illinois in January 2012. Dr Gibbons awarded “founder’s shares in PAI” to us, yet all 5 of us failed to report our financial interests in connection with our article and again in a Reply to Letters to the Editor regarding the article. Neither PAI nor ATT has released the CAT-DI test [or any other test] for commercial or professional use, but our ownership interests were relevant to the research article and Reply we submitted and should have been disclosed to the editors. Our submitted disclosure lacked transparency, and we regret our omission.

Had this unprecedented confession come in a dream? Did he meet the Buddha on the road? We didn’t have to wait very long to hear the answer in a blog post from Dr. Carroll on Healthcare Renewal later in the day. Here’s a sampler from this must-read post:

Hint: When it is made by the Chairman of the DSM-5 Task Force.

Healthcare Renewal

by Bernard Carroll

November 21, 2013

As I am not a person who suffers fools or insults gladly, their evasive response caused me to do some checking. I quickly learned that the gang of five are shareholders in a private corporation. Before their paper was accepted by JAMA Psychiatry, the corporation was incorporated in Delaware and soon after registered to do business in Illinois. Those facts were not disclosed in the original report or in the published letter of Reply to me. These omissions were acknowledged in the notice of Failure to Report that appeared on-line today.

It gets worse. Other things that I learned – and that I communicated to the journal – make it clear that the corporate train had left the station in advance of the letter of Reply. For instance, a professional operations and management executive [Mr. Yehuda Cohen] had joined the corporation. He had established the corporate website, where he was featured as a principal, along with the gang of five. The website also displayed a professionally crafted Privacy Policy, dated ahead of the letter of Reply. This document identified what appears to be a commercial business address for the corporation. The notice of Failure to Disclose is silent on these facts.

So, the published notice of Failure to Disclose still withholds pertinent information, which makes a mockery of the weasel words that they have not released any tests for commercial or professional use. Not yet, they haven’t. But they are under way, make no mistake. This prevarication creates the impression of a habitual lack of transparency. Considering that I gave the journal all this information, one has to be surprised that JAMA Psychiatry went along with this prevarication. Plus, would it have killed them to apologize for their foolish attempt to smear me, as I requested? In correspondence with me, the Editor in Chief of JAMA didn’t want to go there, and he refused to publish my letter that detailed the facts, citing the most specious of grounds. The Editor of JAMA Psychiatry has ducked for cover when I faulted him for publishing the ad hominem material in the first place.

So here in the Introduction, we’ve gone from a story about some waiting room psychometric by a snippy statistician with a hobby of trying to undermine Black Box Warnings on a series of Pfizer’s products to a bigger story about the Chairman of the DSM-5 Task Force, Dr. David Kupfer, being secretly involved in a commercial product being developed on the NIMH dollar – all the while publicly championing that his DSM-5 team is free from outside influence – COIs. That’s one hell of an Introduction. What story can possibly follow an Introduction like that?

Beyond the Introduction

[finally, the story]

It hasn’t been lost on any of us following the story that there’s something very suspicious about Dr. David Kupfer being part of this project. Why is he part of an effort to develop a product to screen for anxiety and depression in waiting rooms of doctor’s offices? That’s hardly his usual line of work. But lest one question his being a member of the PHARMA-friendly KOL set, one doesn’t have to look very far – like to the recent further assault on the antidepressant Black Box Warning [stories like the one told here…], published by the Journal of Psychiatric Research [with article authors and an editorial board that reads like a Who’s Who from this KOL Klan]. But what about Dr. Kupfer’s involvement with this psychometric CAT-DI/CAT-ANX business? That’s where the story is headed.

Those of us following it have been suspicious that there’s something else going on here. This is how I said it after the

apology and the

Healthcare Renewal explanation [

careful watching…]:

… But I have an even further complaint.

Throughout the whole DSM-5 process, they kept talking about adding a "cross-cutting" "dimensional" diagnostic system into the DSM-5. For a long time, I couldn’t even figure out what they were talking about. Towards the end, I finally got it that they were referring to symptoms that "cut" "across" the diagnostic entities – things like anxiety or depression. I was horrified, because I projected that the next step might be asking the FDA to approve medications for these "cross-cutting" diagnoses. Doing a clinical trial on symptomatic anxiety or depression seemed a sure road to rampant over-medication to me. But by the time I figured out what they were talking about, it was clear that the APA trustees weren’t going to approve adding this dimensional system, and I kept my fears to myself.

But when I saw these articles about quick screening tests for anxiety and depression, paid for with NIMH money, a part of a commercial development company, my conspiracy theory radar began to beep out of control. I’m no fan of diagnosis by a symptom list anyway. So the notion of waiting room screening for psychiatric symptoms leading directly to some symptomatic treatment with medications was bad enough. But for the leader of the DSM-5 Task Force who was pushing to make this dimensional system part of the DSM-5 to be involved in a commercial enterprise that would opportunize on the addition takes this story to the level of certifiable scandal.

But I give credit to Phil Hickey at

Behaviorism and Mental Health for doing a yeoman’s job of fleshing out that part of the story. I couldn’t possibly summarize his careful walk-through of the Dimensional System and Dr. Kupfer’s involvement. It’s as much a must-read as Dr. Carroll’s post. But I will copy here Dr. Hickey’s interpretation:

Behaviorism and Mental Health

by Phil Hickey

December 23, 2013

INTERPRETATION

It is difficult to put a benign interpretation on Dr. Kupfer’s role in this matter. It is clear that he believed in the merits of the dimensional system, and that, in his role as DSM-5 Task Force Chair, he promoted this system with as much vigor as he could muster. Even when the APA Board of Trustees voted in December 2012 to retain the categorical approach, he laid the structural groundwork for the introduction of dimensional assessment at a later time, and crafted a numbering system [5.1; 5.2; etc.] whereby the manual can be updated easily and at frequent intervals.

During the DSM-5 deliberations, it was obvious to anyone that if the APA replaced the categorical model with a dimensional model, then there would be a vastly increased market for dimensional rating scales, and that the profit potential was enormous. Given all of this, and given the lack of transparency in the Gibbons et al article, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that Dr. Kupfer’s motivation was at least partly financial, and that he used his position as DSM-5 Task Force Chair to further his own financial agenda.

If a more benign interpretation can be put on these events, I would be interested in hearing it. But it’s clear that psychiatric credibility has taken yet another hit. Dr. Kupfer is a graduate of Yale’s medical school. He joined the University of Pittsburgh in 1973, and became chairman of the psychiatry department in 1983. He continued as department chair until 2009, and is now a professor of psychiatry at that establishment. He has published more than 800 articles, books, and book chapters, and has served on the editorial boards of various journals. And, of course, as mentioned earlier, he served in the prestigious position as chair of the DSM-5 Task Force. He is, in every sense of the term, an eminent psychiatrist.

So I am left with two questions: Firstly, why hasn’t Dr. Kupfer issued some kind of explanation for the lack of transparency? The JAMA Psychiatry letter of apology was just a stark statement of fact, which leaves a huge cloud of doubt not only over Dr. Kupfer, but also over DSM-5 and psychiatry generally. Secondly, why are we not hearing widespread expressions of concern from psychiatry about this matter? To the best of my knowledge, the only psychiatrists who have spoken out on this are Bernard Carroll, who exposed the matter in the first place, and Mickey Nardo, who has been retired for ten years.

This kind of silence in these kinds of situations has become characteristic of psychiatry, through scandal after scandal, in recent years. It is very difficult to avoid the impression that neither psychiatry’s leadership nor its general body has any interest in ethical matters. There is only one agenda item in modern American psychiatry: the relentless expansion of psychiatric turf and drug sales. They’ve promoted categorical diagnoses and chemical imbalances strenuously for the past five decades.Now that these spurious notions are on the point of expiration, psychiatry is developing dimensional diagnoses and neurocircuitry malfunctions as the rallying points of the “new and improved” psychiatry.

But the bottom line is always the same: turf and money. Something is truly rotten in the state of psychiatry.

Things like that last two paragraphs always make me wince. I feel defensive and always wish "organized psychiatry" had been substituted for "psychiatry." But I have to admit that I agree with everything Phil says including that "Something is truly rotten in the state of psychiatry." This is more than a scandal. It’s about a concerted effort to build the entire specialty of psychiatry around psychopharmacology; to make the change to diagnosis by symptom [anxiety and depression]; and to create a screening instrument for waiting rooms that skips even taking a history, wasting the doctor’s valuable time. Look at the printout, prescribe a psychotropic.

It’s sometimes tempting to see critics of psychiatry as the fabled antipsychiatrists who want to destroy psychiatry altogether for a variety of reasons. But if these allegations turn out to be true, Dr. David Kupfer is the antipsychiatrist in this story. He is participating in and encouraging a scheme to trivialize human experience with a quickie waiting room screening instrument that would lead to generic treatment with drugs, eliminating any need for careful evaluation and treatment planning. And he’s done it by operating behind the scenes while being the chief administrator for a medical classification system that would allow just that. This is corruption – not just a story for the blogs. This is for the New York Times, maybe the Congressional Record, and an in-depth investigation of the insider trading it appears to represent…

It would be a gross understatement to say that I see psychiatry in need of reform. So I would’ve thought that on the last day of this particular year, the DSM-5 year, I would look back and feel like Job – sackcloth and ashes. The DSM-5 is many things, but a failed opportunity for reform is on the top of my list – though it’s not so bad as it tried to be. The APA leadership under Dr. Lieberman hasn’t been a plus either.

It would be a gross understatement to say that I see psychiatry in need of reform. So I would’ve thought that on the last day of this particular year, the DSM-5 year, I would look back and feel like Job – sackcloth and ashes. The DSM-5 is many things, but a failed opportunity for reform is on the top of my list – though it’s not so bad as it tried to be. The APA leadership under Dr. Lieberman hasn’t been a plus either. I would be reticent to declare it the dawn of a new day at this point, but a lot of the fog is definitely beginning to lift. So I’ll pass on the sackcloth and ashes this year and look for signs of the missing piece in 2014 – strong forces for change that are originating from within psychiatry itself…

I would be reticent to declare it the dawn of a new day at this point, but a lot of the fog is definitely beginning to lift. So I’ll pass on the sackcloth and ashes this year and look for signs of the missing piece in 2014 – strong forces for change that are originating from within psychiatry itself…

RESULTS: Positive and negative predictors of remission were identified with a 2-way analysis of variance treatment [escitalopram or cognitive behavior therapy] × outcome [remission or nonresponse] interaction. Of 65 protocol completers, 38 patients with clear outcomes and usable positron emission tomography scans were included in the primary analysis: 12 remitters to cognitive behavior therapy, 11 remitters to escitalopram, 9 nonresponders to cognitive behavior therapy, and 6 nonresponders to escitalopram. Six limbic and cortical regions were identified, with the right anterior insula showing the most robust discriminant properties across groups [effect size = 1.43]. Insula hypometabolism [relative to whole-brain mean] was associated with remission to cognitive behavior therapy and poor response to escitalopram, while insula hypermetabolism was associated with remission to escitalopram and poor response to cognitive behavior therapy.

RESULTS: Positive and negative predictors of remission were identified with a 2-way analysis of variance treatment [escitalopram or cognitive behavior therapy] × outcome [remission or nonresponse] interaction. Of 65 protocol completers, 38 patients with clear outcomes and usable positron emission tomography scans were included in the primary analysis: 12 remitters to cognitive behavior therapy, 11 remitters to escitalopram, 9 nonresponders to cognitive behavior therapy, and 6 nonresponders to escitalopram. Six limbic and cortical regions were identified, with the right anterior insula showing the most robust discriminant properties across groups [effect size = 1.43]. Insula hypometabolism [relative to whole-brain mean] was associated with remission to cognitive behavior therapy and poor response to escitalopram, while insula hypermetabolism was associated with remission to escitalopram and poor response to cognitive behavior therapy.