I suppose every discipline has its jargon, words or phrases that have specific meanings that aren’t necessarily found in the general language. If you walk into the waiting room and see someone with bilateral exopthalmos [bulging eyes], you immediately think "Grave’s Disease" [hyperthyroidism]. It’s a pathognomonic sign:

There are other words that are everyday words, but in Medicine have come to have something of an idiosyncratic meaning – for example:

It means something like in this situation, do this. It’s not really as imperative as that sounds – maybe it’s more like this is what is usually done in this situation, so be sure and think about it – and if you don’t do it, have a good reason. At least that’s what I always took it to mean.

I didn’t see detail men in practice, but my partners did. So occasionally, I would get caught. In one such captivity, the sales rep looked at me meaningfully and said with emphasis, "We’ve just found out that we have a new indication for whatever-drug-it-was in whatever-condition-it-was" [as if that had a very special, near mystical significance]. I had never heard it used that way [my ignorance a consequence of chronic avoidance of sales reps]. Later, I asked one of my partners, who explained that the FDA approved drugs for specific diseases or situations. I supposed that was a reasonable idea, a way of communicating what they looked at when they put the drug on the market. I later asked her, "Have they always done that?" She laughed at my by-then legendary naivity in such matters and said, "I don’t know, but what it really means is that they can advertise it for that indication" [truth comes in many forms, and that’s an example].

So I guess there’s another definition for the word:

I’m wiser now. This is why I’ve been so absolutely beside myself that the FDA approved

Brexpiprazole for

Augmentation in Treatment Resistant Major Depressive Disorder. Drugs like Risperdal, Seroquel, or Abilify didn’t make it to the top of the charts in sales because there was an epidemic of psychotic illness. They got there by getting other

indications for more prevalent conditions. And industry plans for such things well in advance, like with their clinical trials [see

extending the risk…]. As

Tone Jones said at the TMAP Trial, "

You can’t be a billion dollar drug in a 1% market."

Which brings me to this report I ran across on MEDPAGE TODAY. It’s about Vortioxetine [Brintellix®] and a recent long day at the FDA:

Panel debates vortioxetine for treating cognitive dysfunction in major depression

MEDPAGE TODAY

by Kristina Fiore

02/03/2016

An FDA advisory committee voted 8-to-2 to give the antidepressant vortioxetine [Brintellix] a new indication for cognitive dysfunction in major depressive disorder [MDD]. The decision followed an unusual meeting format for the Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee, with the first half of the day dedicated to discussing whether or not cognitive dysfunction in MDD is a suitable target for development, and if so, how exactly it should be studied…

Historically, the FDA’s division of psychiatry products within Center for Drug Evaluation and Research has taken the position that cognitive dysfunction in MDD was a pseudo-specific drug target, "meaning that this claim would be considered artificially narrow and related to the overall disorder of MDD," the agency wrote in review documents posted ahead of the meeting. But the organization changed its stance as more research has suggested that it can be considered a distinct problem that hasn’t been evaluated in drug trials.

Starting in 2011, Lundbeck, the original developer of vortioxetine, began submitting data on the drug’s efficacy in cognitive dysfunction to the FDA. In 2014, Takeda and Lundbeck met with FDA to further discuss the potential indication, and the agency ultimately decided on a public hearing to discuss both the possibility of such an indication and the efficacy of the drug on the same day…

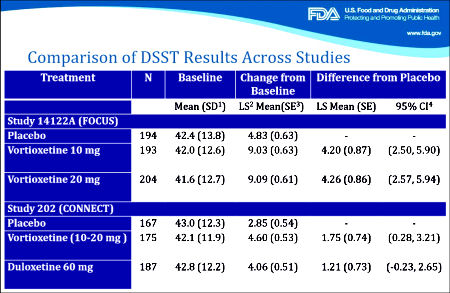

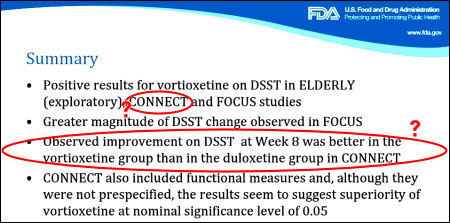

In one of the approval trials, called ELDERLY, vortioxetine offered better results on the digit symbol substitution test [DSST] than duloxetine, prompting the companies to open two other trials focused on cognitive impairment in MDD: FOCUS and CONNECT, both of which enrolled 602 patients for an 8-week trial period. FOCUS looked at a composite of DSST plus Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test [RAVLT] learning and memory for its primary endpoint, while CONNECT looked only at DSST — and both showed an effect, albeit a small one, according to FDA clinical reviewer Wen-Hung Chen, PhD…

Should the FDA decide that cognitive dysfunction in MDD is indeed a valid therapeutic target and that Takeda has demonstrated that vortioxetine improves the condition, the two groups will work together to define the exact terms of the labeling. The agency is not obliged to follow recommendations from its advisory committees, but it usually does.

Vortioxetine was a late comer to the antidepressant scene [2013] and I haven’t paid much attention to it since that bizarre review article in the

Journal of Clinical Psychiatry [see

the recommendation?…]. This piece caught my attention because of the

indication creep, but I also wondered what an FDA Advisory group had seen that would have them voting 8:2 in favor of this new indication. Then after I scanned the abstracts, I found something else that piqued my curiosity. First, here are the papers:

by McIntyre RS, Lophaven S, and Olsen CK.

International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014 17[10]:1557-1567.

The efficacy of vortioxetine 10 and 20 mg/d vs. placebo on cognitive function and depression in adults with recurrent moderate-to-severe major depressive disorder [MDD] was evaluated. Patients [18-65 yr, N = 602] were randomized [1:1:1] to vortioxetine 10 or 20 mg/d or placebo for 8 wk in a double-blind multi-national study. Cognitive function was assessed with objective neuropsychological tests of executive function, processing speed, attention and learning and memory, and a subjective cognitive measure. The primary outcome measure was change from baseline to week 8 in a composite z-score comprising the Digit Symbol Substitution Test [DSST] and Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test [RAVLT] scores. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale [MADRS]. In the pre-defined primary efficacy analysis, both doses of vortioxetine were significantly better than placebo, with mean treatment differences vs. placebo of 0.36 [vortioxetine 10 mg, p < 0.0001] and 0.33 [vortioxetine 20 mg, p < 0.0001] on the composite cognition score. Significant improvement vs. placebo was observed for vortioxetine on most of the secondary objectives and subjective patient-reported cognitive measures. The differences to placebo in the MADRS total score at week 8 were -4.7 [10 mg: p < 0.0001] and -6.7 [20 mg: p < 0.0001]. Path and subgroup analyses indicate that the beneficial effect of vortioxetine on cognition is largely a direct treatment effect. No safety concern emerged with vortioxetine. Vortioxetine significantly improved objective and subjective measures of cognitive function in adults with recurrent MDD and these effects were largely independent of its effect on improving depressive symptoms.

by Atul R Mahableshwarkar, John Zajecka, William Jacobson, Yinzhong Chen and Richard SE Keefe

Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015 40: 2025–2037.

This multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, active-referenced [duloxetine 60 mg], parallel-group study evaluated the short-term efficacy and safety of vortioxetine [10-20 mg] on cognitive function in adults [aged 18-65 years] diagnosed with major depressive disorder [MDD] who self-reported cognitive dysfunction. Efficacy was evaluated using ANCOVA for the change from baseline to week 8 in the digit symbol substitution test [DSST]-number of correct symbols as the prespecified primary end point. The patient-reported perceived deficits questionnaire [PDQ] and physician-assessed clinical global impression [CGI] were analyzed in a prespecified hierarchical testing sequence as key secondary end points. Additional predefined end points included the objective performance-based University of San Diego performance-based skills assessment [UPSA] [ANCOVA] to measure functionality, MADRS [MMRM] to assess efficacy in depression, and a prespecified multiple regression analysis [path analysis] to calculate direct vs indirect effects of vortioxetine on cognitive function. Safety and tolerability were assessed at all visits. Vortioxetine was statistically superior to placebo on the DSST [P < 0.05], PDQ [P < 0.01], CGI-I [P < 0.001], MADRS [P < 0.05], and UPSA [P < 0.001]. Path analysis indicated that vortioxetine’s cognitive benefit was primarily a direct treatment effect rather than due to alleviation of depressive symptoms. Duloxetine was not significantly different from placebo on the DSST or UPSA, but was superior to placebo on the PDQ, CGI-I, and MADRS. Common adverse events [incidence ? 5%] for vortioxetine were nausea, headache, and diarrhea. In this study of MDD adults who self-reported cognitive dysfunction, vortioxetine significantly improved cognitive function, depression, and functionality and was generally well tolerated.

I highlighted the part I was curious about. What was this path analysis that would lead them to claim that the effect on cognition was a direct effect, rather than secondary to improvements in depression? On a first pass through these articles, I couldn’t follow their path analysis well enough to understand it, so I linked all the reference material for a rainy day or in case there’s someone out there quicker than I who can explain it to us right now. According to the Medscape article linked above, the FDA will consider this new indication next month, "The agency is expected to make a decision on this new sNDA by March 28, according to the press release." While I didn’t follow their path analysis, the overall analysis of effect sizes was standard fare – and like the two dissenting FDA panelists, I thought they weren’t at all impressive:

Primary Analysis Based on the ANCOVA analysis, the change from baseline [mean±SE] to week 8 in DSST performance score was 4.60±0.53 for vortioxetine, 4.06±0.51 for duloxetine, and 2.85±0.54 for placebo.

The difference from placebo was significant for vortioxetine [Δ +1.75, 95% CI: 0.28, 3.21;

P=0.019; ANCOVA, OC], with a standardized effect size of 0.254. The difference from placebo was not significant for the duloxetine group [Δ +1.21, 95% CI: −0.23, 2.65;

P=0.099], with a standardized effect size of 0.176.

I’m skeptical about this claim of an independent effect on cognition myself, a skepticism born from both experience and their data. However, the meaning to the Sponsors is clear. If the FDA approves this new indication, we can easily envision that the Cohen’s d of 0.254 [weak] will turn into the kind of difference that’s a marketing department’s dream come true. "Depressed? Having trouble thinking? Brintellix® has been shown to …" all the while hoping to create a blockbuster in spite of the fact that the antidepressant effect was less that the active comparator Duloxetine.

Depression Outcome

The study was validated because both vortioxetine and duloxetine demonstrated a statistically significant change from baseline in mood symptoms compared with placebo at the end of week 8, as measured by change in MADRS [vortioxetine, Δ − 2.3, 95% CI: − 4.3, − 0.4; P < 0.05; duloxetine, Δ − 3.3, 95% CI: − 5.2, − 1.4; P < 0.001; MMRM, FAS].

With

54 clinical trials of

vortioxetine on clinicaltrials.gov, 6 of them directly addressing cognition along with the other fishing expeditions looking for

indications, the dance between the FDA and industry that has been a major feature of psychopharmacology drug trials continues to play out on a stage of p-values, weak effect sizes, and small differences, just like it has for the last 30 years. Where are the grown-ups?

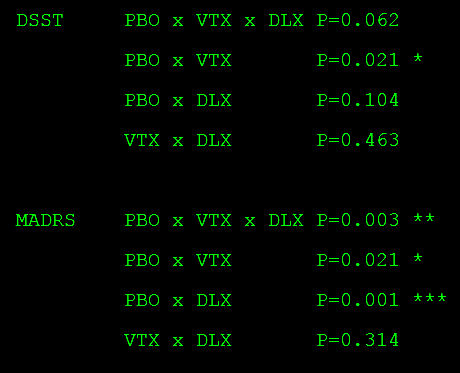

NOTE: from

Table 2 in Keefe et al [2015]. Since we don’t have the actual data, the only way we can do the Omnibus ANOVA is from

summary data. Nevertheless, in the DSST analysis, it is

not significant. A strict interpretation of that finding invalidates any differences in the pair-wise comparisons. Also note that in both the DSST and MADRS analyses, Vortioxetine and Duloxetine are

not statistically different.

The story with this Brintellix® application for approval is the same issue – a failed replication. Their second study [CONNECT] did not reproduce the results of the earlier trial [FOCUS]. While there are lots of other questions about approval for this indication, they’re in the background to this non-replication. So it’s a dangerous time because here’s another situation where they’re about to give a drug the benefit of the doubt if they follow the recommendations of the advisory committee [see more vortioxetine story…]. There’s no reason to do that. Brintellix® has never beaten another antidepressant head-to-head – and this indication [Cognitive Dysfunction in Major Depressive Disorder] seems both contrived and unproven.

The story with this Brintellix® application for approval is the same issue – a failed replication. Their second study [CONNECT] did not reproduce the results of the earlier trial [FOCUS]. While there are lots of other questions about approval for this indication, they’re in the background to this non-replication. So it’s a dangerous time because here’s another situation where they’re about to give a drug the benefit of the doubt if they follow the recommendations of the advisory committee [see more vortioxetine story…]. There’s no reason to do that. Brintellix® has never beaten another antidepressant head-to-head – and this indication [Cognitive Dysfunction in Major Depressive Disorder] seems both contrived and unproven.

The difference from placebo was significant for vortioxetine [Δ +1.75, 95% CI: 0.28, 3.21; P=0.019; ANCOVA, OC], with a standardized effect size of 0.254. The difference from placebo was not significant for the duloxetine group [Δ +1.21, 95% CI: −0.23, 2.65; P=0.099], with a standardized effect size of 0.176.

The difference from placebo was significant for vortioxetine [Δ +1.75, 95% CI: 0.28, 3.21; P=0.019; ANCOVA, OC], with a standardized effect size of 0.254. The difference from placebo was not significant for the duloxetine group [Δ +1.21, 95% CI: −0.23, 2.65; P=0.099], with a standardized effect size of 0.176. The study was validated because both vortioxetine and duloxetine demonstrated a statistically significant change from baseline in mood symptoms compared with placebo at the end of week 8, as measured by change in MADRS [vortioxetine, Δ − 2.3, 95% CI: − 4.3, − 0.4; P < 0.05; duloxetine, Δ − 3.3, 95% CI: − 5.2, − 1.4; P < 0.001; MMRM, FAS].

The study was validated because both vortioxetine and duloxetine demonstrated a statistically significant change from baseline in mood symptoms compared with placebo at the end of week 8, as measured by change in MADRS [vortioxetine, Δ − 2.3, 95% CI: − 4.3, − 0.4; P < 0.05; duloxetine, Δ − 3.3, 95% CI: − 5.2, − 1.4; P < 0.001; MMRM, FAS].

At some other point, we might not have paid a lot of attention or even noticed the appointment of a new FDA Commissioner. For that matter, I wonder if we would have been aware that the position of Director of the NIMH has just been vacated. But right now, both have been on the front burner. Besides their obvious centrality in the ‘hot topic’ of pharmaceuticals, a prime subject in our daily news, there’s something else that connects them – their relationship to the information age and its big data. Both are intrigued by and involved in the application of these new technologies to how we do medical research and specifically how they relate to the clinical trials we use to evaluate medications.

At some other point, we might not have paid a lot of attention or even noticed the appointment of a new FDA Commissioner. For that matter, I wonder if we would have been aware that the position of Director of the NIMH has just been vacated. But right now, both have been on the front burner. Besides their obvious centrality in the ‘hot topic’ of pharmaceuticals, a prime subject in our daily news, there’s something else that connects them – their relationship to the information age and its big data. Both are intrigued by and involved in the application of these new technologies to how we do medical research and specifically how they relate to the clinical trials we use to evaluate medications. He’s certainly well represented in our medical literature. His name is on over 1100 articles indexed in

He’s certainly well represented in our medical literature. His name is on over 1100 articles indexed in  What a good compromise. Is it possible that Congressmen might wake up from their long sleep and do something so clearly sensible as this? As I read it, I thought, "And maybe require that they have to add the price per pill to the ad." The pharmaceutical companies moan about all the hoops they have to jump through, but I have a hard time generating any sympathy for their complaints. They can’t imagine the burden they’ve added to the practice of medicine with the ubiquitous "ask your doctor if ____ is right for you." Beside the direct effect of specific requests, it seems to me like it’s part of a change in many patients’ approach to medicine in general.

What a good compromise. Is it possible that Congressmen might wake up from their long sleep and do something so clearly sensible as this? As I read it, I thought, "And maybe require that they have to add the price per pill to the ad." The pharmaceutical companies moan about all the hoops they have to jump through, but I have a hard time generating any sympathy for their complaints. They can’t imagine the burden they’ve added to the practice of medicine with the ubiquitous "ask your doctor if ____ is right for you." Beside the direct effect of specific requests, it seems to me like it’s part of a change in many patients’ approach to medicine in general.  One might see this state of affairs as including the patient in the decision about treatment. I’m fine with including the patient in decisions about treatment. But I’m not at all fine with those ads ability to create patients, or to suggest that there’s magic in antipsychotics for people who tried to find magic in the antidepressants that came before them, when the actual problem is in the "psycho-social" domain. I don’t like thinking these thoughts particularly, but this "agenda trend" is very real and it’s coming from someplace. The ads may well be aimed at creating a market for specific drugs, but they reinforce the idea that the solution to life’s woes comes in a potion of some kind. And I recurrently wonder how much that contributes to things like this article in my local paper.

One might see this state of affairs as including the patient in the decision about treatment. I’m fine with including the patient in decisions about treatment. But I’m not at all fine with those ads ability to create patients, or to suggest that there’s magic in antipsychotics for people who tried to find magic in the antidepressants that came before them, when the actual problem is in the "psycho-social" domain. I don’t like thinking these thoughts particularly, but this "agenda trend" is very real and it’s coming from someplace. The ads may well be aimed at creating a market for specific drugs, but they reinforce the idea that the solution to life’s woes comes in a potion of some kind. And I recurrently wonder how much that contributes to things like this article in my local paper.