Posted on Thursday 11 September 2014

I’ve noticed that there’s a pattern in this blog [and in your responses]. I write a post, and something sticks in my mind, and I chase it in the next. That often goes on for a couple of iterations. It’s apparently how I think. Readers tend to comment the first time around, then run out of juice as I perseverate on things for a while. That seems reasonable. This is one of those perseveration posts – I’m still on the Hickie/Rogers review of agomelatine [which is beginning to smell like the "Study 329" of review articles]. If you’re over it, you might want to skip this one [and maybe the next one too]. I come by my 1boringoldman moniker honestly…

Without my really planning it, my last three posts have relied on the work of the same authors, Dr. Andrea Cipriani and Corrado Barbui, who were at the University of Verona at the time these articles were written. Dr. Cipriani is now at the University of Oxford and the Editor in Chief of Evidence-Based Mental Health [the journal of the article below], the Editorial Board of Lancet Psychiatry, and one of the Editors of the Cochrane Collaboration for Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis. They have been involved with many of the Cochrane Reviews of the Antidepressants [and may deserve the title clinical trial gurus in a different way than Dan Sfera of South Coast Clinical Trials].

by Corrado Barbui and Andrea CiprianiEvidence Based Mental Health. 2012 15:2-3.Introduction: … This essay aims at raising awareness on the need to set a standard for reporting clinical data in articles dealing with basic science issues.

Claims of efficacy in review articles on the pharmacology of agomelatine: The most recent review article on the pharmacology of agomelatine was published by Hickie and Rogers. In this report, a table summarised the placebo-controlled and active comparator trials of agomelatine in individuals with major depression, and in the accompanying text it is clearly stated that agomelatine has clinically significant antidepressant properties. It is reported that it is more effective in patients with more severe depression, and that agomelatine is similarly effective in comparison with some comparator antidepressants, and is more effective than fluoxetine. In terms of tolerability, Hickie and Rogers reported a safe profile, and concluded that agomelatine might occupy a unique place in the management of some patients with severe depression…

The content of these reports is in line with the content of most recently published reports on the chronobiotic effect of agomelatine and other melatonin agonists. A PubMed search [June 17th 2011 back to January 1st 2009] using the terms ‘agomelatine’ and ‘depression’ identified 73 hits of which 34 were review articles on agomelatine as a new option for depression treatment. On the basis of the abstract, we noted that 80% of these reports made claims of efficacy of agomelatine as an antidepressant, 41%7 reported a safe tolerability profile and only four reports mentioned that agomelatine is probably hepatotoxic.

The problem: narrative-based approach to evidence synthesis: We note that these articles make claims of efficacy that are based on narrative rather than systematic reviews of the evidence base. In addition, lack of a methodology to summarise the results of each clinical trial, and lack of overall treatment estimates, make data interpretation rather difficult. As a consequence, often claims of efficacy are not consistent with the efficacy data that are presented. A re-analysis of the efficacy of agomelatine versus placebo, carried out applying standard Cochrane methodology to the data reported in table 3 and table 4 of the Hickie and Rogers report, revealed that agomelatine 25 mg and agomelatine 50 mg have minimal antidepressant efficacy, with no dose-response gradient [table 1]. In comparison with placebo, acute treatment with agomelatine is associated with a difference of 1.5 points at the Hamilton scale. No research evidence or consensus is available about what constitutes a clinically meaningful difference in Hamilton scores, but, as reported by some authors of agomelatine clinical trials, it seems unlikely that a difference of less than 3 points could be considered clinically meaningful. In addition, a bias in properly assessing the depressive core of major depression may exist with the Hamilton scale, leaving the possibility that a 1.5 difference may only reflect a weak effect on sleep regulating mechanisms rather than a genuine antidepressant effect…

Re-analyses of the efficacy of agomelatine versus control antidepressants revealed that agomelatine is not more effective than fluoxetine [table 1] and might be less effective than paroxetine, although results are heterogeneous and of borderline statistical significance [table 1]. In the abstract of the Hickie and Rogers article the results of the comparisons between agomelatine and some control antidepressants are mentioned, but the comparison between agomelatine and paroxetine is omitted. The authors reported similar efficacy between agomelatine and venlafaxine, and better efficacy in comparison with sertraline. However, these results, based only on one study for each comparator antidepressant, are not placed in perspective, and no attempt has been made to critically contextualise their conclusions with what is already known. For example, the pattern of comparative efficacy of agomelatine does not fit with a recent network meta-analysis which showed sertraline and venlafaxine on the top of the efficacy ranking and paroxetine among the least effective antidepressants.

In terms of tolerability, most reviews did not mention the potential relationship between agomelatine and hepatic problems. According to the European Medicine Agency, increases in liver function parameters were reported commonly in the clinical documentation [on 50 mg agomelatine] and in general, more often in agomelatine treated subjects than in the placebo group, leading to the cautionary note that agomelatine is contraindicated in patients with hepatic impairment…

In terms of long-term data, according to these reports the protective role of agomelatine is considered a well-established finding. However, in the Hickie and Rogers article three long-term studies are described, two negative and one positive comparisons between agomelatine and placebo. For one of the two negative studies, efficacy data are not available, and therefore re-analysis was not possible. In the text of the article and in the abstract, only the positive study is mentioned.

Expected consequences: Expected consequences are that these review articles will be highly disseminated by pharmaceutical representatives, keen to extol the virtue of their product, and clinicians’ behaviour will be moulded by the clinical data presented and formularies restructured based on their conclusions…

What can be done – quickly, easily and with no additional costs: Innovation in clinical psychopharmacology is of paramount importance, as current pharmacological interventions for mental disorders suffer from several limitations. However, we argue that reporting of clinical trial results, even in review articles that are focused on new biological mechanisms, should follow a standard of reporting similar to that required from authors of systematic reviews. We recently applied this reasoning to the documents released by the European Medicine Agency, as this standard should be considered a term of reference irrespective of the nature of the report being disseminated. If the clinical data presented in the review articles on the pharmacology of agomelatine had been analysed with standard Cochrane methodology, conclusions would have been that the efficacy of agomelatine is minimal. Comparisons with other antidepressants are only partly informative, because there were only few trials and because of the high between-study heterogeneity. Long-term data are inconclusive. Clearly, different doctors may interpret the same evidence base differently and, for example, the difference between agomelatine and placebo might be described as modest rather than minimal, the bottom line being basically the same and radically different from the take-home messages of these reviews.Most medical journals require adherence to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA).12 It is an evidence-based minimum set of items for reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Adherence to PRISMA is not required in review articles dealing with basic science issues as these articles are not focused on clinical trials. In practice, however, the agomelatine case indicates that clinical data are regularly included and reviewed with no reference to the rigorous requirements of the PRISMA approach. These articles have this way became a modern Trojan horse for reintroducing the brave old world of narrative-based medicine into medical journals.

We argue that medical journals should urgently apply this higher standard of reporting, which is already available, easy to implement and inexpensive, to any form of clinical data presentation. Lack of such a standard may have negative consequences for practising doctors who may be erroneously induced to prescribe drugs that may be less effective, or less tolerable, than others already in the market, with additional acquisition costs for patients and the wider society. This risk is particularly high when medical journals with a high reputation are involved.

Dr. Roy Poses of

Dr. Roy Poses of

Irving Kirsch published an article in 2008 [

Irving Kirsch published an article in 2008 [

The PROTOCOL is a formal document that lays out in detail how the study is to be conducted. It has multiple functions, but for our purposes, it’s important because there are a number of ways that a study can be skewed in favor of a drug – like picking a dose for the comparator drug that is either to low to be effective or to high and likely to cause a number of side effects and discontinuations. It’s important because it lays out the primary and secondary variables and how they will be analyzed. All of this is a priori, before the study is done. One reason is that given enough creativity, one can frequently find significance after the fact by running tests on any and everything. By making a priori declarations of both target and technique, the PROTOCOL assures us that we’re not being taken down some after-the-fact garden path. The PROTOCOL is an essential element for Data Transparency.

The PROTOCOL is a formal document that lays out in detail how the study is to be conducted. It has multiple functions, but for our purposes, it’s important because there are a number of ways that a study can be skewed in favor of a drug – like picking a dose for the comparator drug that is either to low to be effective or to high and likely to cause a number of side effects and discontinuations. It’s important because it lays out the primary and secondary variables and how they will be analyzed. All of this is a priori, before the study is done. One reason is that given enough creativity, one can frequently find significance after the fact by running tests on any and everything. By making a priori declarations of both target and technique, the PROTOCOL assures us that we’re not being taken down some after-the-fact garden path. The PROTOCOL is an essential element for Data Transparency.  T

T T

T he IPD [INDIVIDUAL PARTICIPANT DATA] is the compilation of the data from the CRFs in tabular form, spreadsheets in one format or another, data transposed from the CRFs and ready for analysis [separated by treatment eg after the blind has been broken]. For an analysis of the efficacy data, this is all that would be required. The adverse event data is also usually in tabular form in either an abbreviated or encoded in some standardized way. If there are no questions about adverse events, the IPD tables would be fine for a reanalysis. But if adverse event data is in question, the actual CRFs are required reading to avoid lost-in-translation errors, as tedious as that might be.

he IPD [INDIVIDUAL PARTICIPANT DATA] is the compilation of the data from the CRFs in tabular form, spreadsheets in one format or another, data transposed from the CRFs and ready for analysis [separated by treatment eg after the blind has been broken]. For an analysis of the efficacy data, this is all that would be required. The adverse event data is also usually in tabular form in either an abbreviated or encoded in some standardized way. If there are no questions about adverse events, the IPD tables would be fine for a reanalysis. But if adverse event data is in question, the actual CRFs are required reading to avoid lost-in-translation errors, as tedious as that might be.

The published ARTICLE is what we’re used to seeing. There was a time in my lifetime that we thought that what we read in our journals was the real deal, but that time has passed. The many ways that data has been manipulated, misrepresented, jury-rigged, seen through rose-colored glasses has become a source of daily amazement to me in my retirement years. As I’ve often said, never in my wildest dreams. There are so many examples that industry really doesn’t have much of a legitimate argument for their claim of proprietary ownership of Clinical Trial data. Their record of gross abuse of that privilege is self-indicting.

The published ARTICLE is what we’re used to seeing. There was a time in my lifetime that we thought that what we read in our journals was the real deal, but that time has passed. The many ways that data has been manipulated, misrepresented, jury-rigged, seen through rose-colored glasses has become a source of daily amazement to me in my retirement years. As I’ve often said, never in my wildest dreams. There are so many examples that industry really doesn’t have much of a legitimate argument for their claim of proprietary ownership of Clinical Trial data. Their record of gross abuse of that privilege is self-indicting.

Mentally ill persons increasingly receive care provided by corrections agencies. In 1959, nearly 559,000 mentally ill patients were housed in state mental hospitals. A shift to "deinstitutionalize" mentally ill persons had, by the late 1990s, dropped the number of persons housed in public psychiatric hospitals to approximately

Mentally ill persons increasingly receive care provided by corrections agencies. In 1959, nearly 559,000 mentally ill patients were housed in state mental hospitals. A shift to "deinstitutionalize" mentally ill persons had, by the late 1990s, dropped the number of persons housed in public psychiatric hospitals to approximately  70,000. As a result, mentally ill persons are more likely to live in local communities. Some come into contact with the criminal justice system.

70,000. As a result, mentally ill persons are more likely to live in local communities. Some come into contact with the criminal justice system.

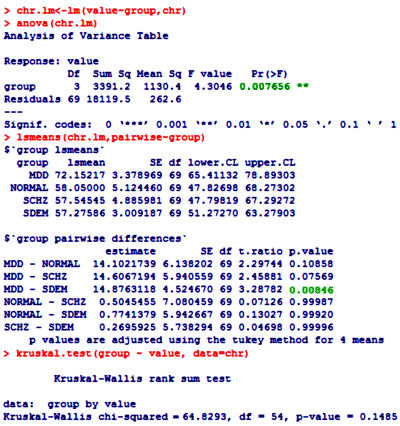

One of the most frustrating things about papers like this is that the raw data isn’t available, even if one has the time to go over it in detail. Once again, I find myself looking at a graph that I’m told is meaningful, significant, has something to say important about a major psychiatric syndrome. And what I see looks like a trivial difference that is probably meaningless, and I even doubt significant. So I did something that I’ve been tempted to do many times. I opened it in a graphics program and reconstituted the data by measuring the pixel count to the center of each data point and using that table, the baseline, and the ordinate scale to reproduce the data. I wouldn’t recommend this on a Nobel Prize application or even in a paper, but I thought I’d give it a shot because I don’t believe the analysis is correct, or correctly done [the next paragraphs is only for the hardy].

One of the most frustrating things about papers like this is that the raw data isn’t available, even if one has the time to go over it in detail. Once again, I find myself looking at a graph that I’m told is meaningful, significant, has something to say important about a major psychiatric syndrome. And what I see looks like a trivial difference that is probably meaningless, and I even doubt significant. So I did something that I’ve been tempted to do many times. I opened it in a graphics program and reconstituted the data by measuring the pixel count to the center of each data point and using that table, the baseline, and the ordinate scale to reproduce the data. I wouldn’t recommend this on a Nobel Prize application or even in a paper, but I thought I’d give it a shot because I don’t believe the analysis is correct, or correctly done [the next paragraphs is only for the hardy].